Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo/Slate. Photos by

photosmash/iStock/Getty Images Plus, Michael Burrell/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

When the bar where she worked closed three weeks ago, Maria found herself out of a job. Her 17-year-old son has been home all day playing cellphone games since schools closed in the middle of March. The family has no computer, which makes it hard for her son to keep up with his classes, and hard for her to find work. Her oldest son lost his job too, in a pizzeria on the campus of a local university, which, like everything, is closed.

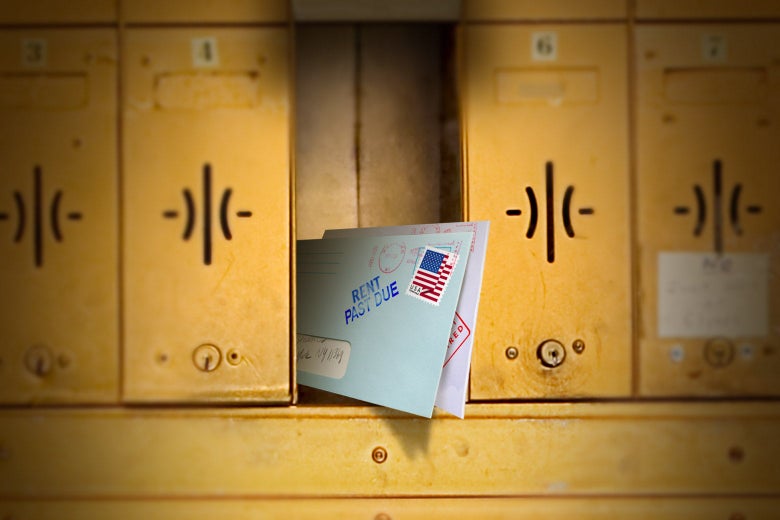

In many respects Maria’s story is typical of low-income Americans, laid off by their employers, turned away from shuttered institutions, and cut off from typical support networks due to social distancing. Except that Maria is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. (Her name, like others in this story, has been changed at her request.) So while her neighbors file for unemployment insurance and await $1,200 checks from the government, Maria dips into her meager savings account to keep the heat on. She does not know how she will pay the rent, due on April 15—or even how to communicate to her landlord that she can’t pay, because she doesn’t speak English. And there’s no sign she’ll need to clean the bar anytime soon.

As the coronavirus lockdowns deepen, no group finds itself in a more difficult situation than America’s 12 million undocumented immigrants. Certainly, none is less likely to get the help it needs.

Eréndira Rendón, a DACA recipient who runs immigration work at the Chicago-based Resurrection Project, says immigrants need the same thing native-born Americans do: cash. Boosts to programs like SNAP, unemployment insurance, or Medicaid won’t help Rendon’s undocumented parents, who have lost their income since her mom came down with a possible, untested COVID-19 case in mid-March. Her father, who is diabetic, is stocking up on insulin at the advice of his doctor. Her brother’s handyman business has dried up. “No one in my family is making any money,” she said.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement has said it will “temporarily adjust its enforcement posture,” away from the workplace raids that have characterized its Trump-era conduct. The Department of Homeland Security has declared farmworkers “essential,” offering rare (and extremely self-interested) recognition of one of the many vital roles that America’s shadow workforce plays. (Meanwhile, the administration has used the crisis to turn away thousands of migrants at the southern border, including children and asylum-seekers.)

But for the likely hundreds of thousands of undocumented service-sector, manufacturing, and construction workers who have lost their jobs, there is no safety net, and no effort from the U.S. Congress to address their plight. Asked how undocumented Americans will survive the shutdown, Donald Trump delivered a typical stammering nonanswer.

It’s not just legal uncertainty that puts undocumented residents in a tough place right now. About half of undocumented Americans don’t have insurance, and may be reluctant to seek treatment for Covid-19. And nearly half of all U.S. Hispanics, who make up a large share of the undocumented population, have been laid off or taken a pay cut as a result of the coronavirus, according to Pew. That’s compared to one-third of all U.S. adults. Many who do still have work worry their jobs, in dangerous industries like construction and meatpacking, put them at risk of getting sick.

“The main thing right now is paying rent,” says Anel Sancen, a census organizer with Mujeres Latinas en Acción, a Chicago-based nonprofit. “There’s no money, and they can’t get no money.” Mujeres is one of several Chicagoland nonprofits distributing some of the $9 million disbursed by United Way’s Chicago Community COVID-19 Response Fund, in the form of $500 grants.

But, Sancen said, it’s clear this money is not enough. There are about 200,000 undocumented immigrants living in Chicago, and about twice that many in the metro area. Her organization, like others distributing charity, has been forced to determine who among many needy applicants is at the greatest risk.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot signed an order on Tuesday that allowed undocumented residents to access the city’s relief programs, including resources for small businesses and $1,000 housing grants from the city’s affordable housing fund. But here too, the supply is far outmatched by demand. In seven days, more than 83,000 people applied for just 2,000 housing grants. While Cook County, like many jurisdictions, has suspended evictions, there has been no policy preparation for what happens when housing courts reopen.

Chicago is typical. The same crisis is playing out across U.S. cities, like Los Angeles and Houston, where the country’s immigrant workforce is concentrated, and in rural America where big demographic changes have occurred in the past decade. Some lawmakers, including California Gov. Gavin Newsom and US Rep. Rashida Tlaib, of Michigan, have proposed policies to help undocumented Americans pay the bills. But so far, most of the load has fallen to churches and charities.

Nationally, almost one-third of U.S. apartment tenants didn’t pay rent at the start of April, according to the National Multifamily Housing Council. Rafael Leon, the director of the Chicago Metropolitan Housing Development Corporation, a nonprofit that owns 750 affordable units in and around the city, typically receives $700,000 in rent rolls a month. “My expectation is we lose half of that,” he said.

But if the lockdown goes on, the savings accounts of undocumented families will begin to run dry. It’s a cruel turn for workers who have paid so much in taxes, in some cases for decades, to be hung out to dry during a pandemic. For once, the willingness to work as much as it takes, at the jobs Americans won’t do, for little money, in dangerous conditions, isn’t much help.

On Chicago’s West Side, the clock is ticking for Carmen, an undocumented Mexican immigrant and mother of three whose income vanished when she lost her job cleaning offices last month. Her husband, who works in a bread factory, has had his working hours cut from five days a week to three. Like many parents, she’s become a de facto teacher, helping her young children through their workbooks, but doesn’t know how the family will pay next month’s rent if the shutdown continues.

She has applied for a job at the local grocery store, which seems to the only thing open in her neighborhood, but she hasn’t heard back.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3cbxAg7

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言