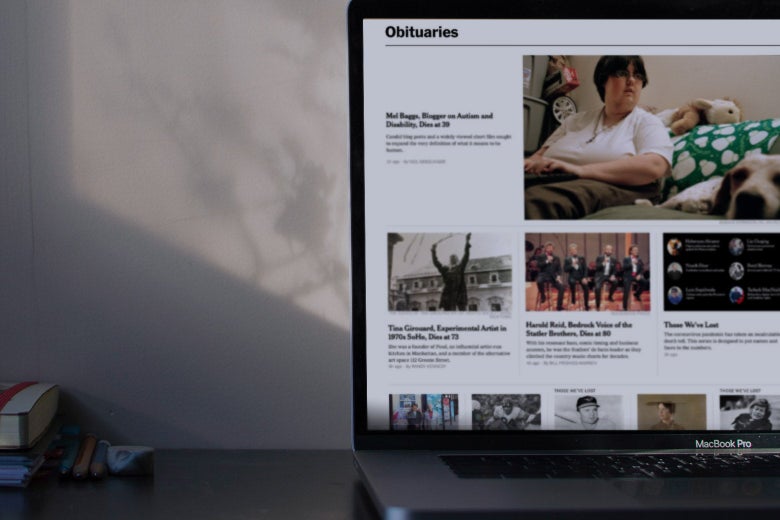

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Émile Perron on Unsplash and New York Times.

Slate is making its coronavirus coverage free for all readers. Subscribe to support our journalism. Start your free trial.

William McDonald has been the editor of the New York Times’ Obituaries section since 2006, a long tenure that did very little to prepare him or his team for the coronavirus. What started as an email from a colleague while the staff was still working at 620 Eighth Ave. has morphed into the sprawling Those We’ve Lost series, a project McDonald helps oversee from a living room he’s turned into an office. We spoke on a recent afternoon about when he began to notice a spike in submissions, preparing Boris Johnson’s obituary, and how the pandemic is changing who the Times profiles in death. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jeffrey Bloomer: When did you start to realize the scale of what was coming, and how did you start to plan for it when you did?

William McDonald: We were still in the office at the time. We saw this developing, like everybody else, with growing alarm. Sam Roberts, who’s one of our crack writers—he’s a longtime New York Times correspondent and editor—he’s with our group and he originally floated the idea of whether we should be doing something like our 9/11 Portraits of Grief project. He had the thought maybe before the rest of us did. And he was right.

Portraits of Grief actually was done by the Metro Desk at the time, not the obituary section. But those were a finite number of people who had died. And it took several months for the paper to actually account for, I think, almost all of them, if not all of them.

“There is tremendous reader interest in who exactly is succumbing to this.” — William McDonald

This is something much different. The scale is different by orders of magnitude. Some people thought, oh, it’s beyond our scope. We’re just a small group. Obviously, we cannot report on all the deaths. There were too many. So we decided to do something like a cross section of deaths. We were getting emails, we were getting notified by others outside too, about the various deaths. It overtook us in a way too, this tide of deaths. It was becoming startling and shocking how many people there were, and with great stories. Great lives were being lost. And we wanted to account for some of them. We wanted to make the point, I suppose, implicitly, that this disease was hitting people from all walks of life.

It wasn’t clear how vast it was going to be. We thought we could do maybe, in print, one page. And that quickly fell by the wayside. We thought, well, we need to do more than one page a week. We can get five or six obits on a page. We’re now up to two pages. Then the website itself is vastly overwhelming what we can do in print. It took on a life of its own, and here we are.

Today there were 4,500 deaths. Can you tell me how you are managing and prioritizing which ones you cover?

We decided to do not just the famous. Like Terrence McNally was one of the bigger names we had originally. But the bus drivers, and the nurses, and the doctors, and professors who might not have gotten an obituary in the Times before, we’re doing that now. We’re just trying to be as broad as we can but also try to present a range of people both internationally and nationally. And it’s just the tip of the iceberg, we acknowledge. And it doesn’t try to be comprehensive in any way. But it is, I think, a kind of glimpse into what this pandemic is doing, how it’s just ripping through all elements of society.

One of the first obits that I think really broke out, from the Times but also just in general, was for Dez-Ann Romain. She was a principal at a high school in Brooklyn. There was a very powerful picture of her, and she was young. I saw that everywhere. Are you noticing any trend in whose stories are breaking through right now, with so many people dying?

That was a particularly powerful one. I think we had one the other day about a young woman in the Bronx. She was 25 years old. She was studying to be a family therapist with a concentration on Latino families. And you know, just in her life, she was blossoming. And she died of this. That was heartbreaking. And that one also got a tremendous readership. I think when you see younger people dying of this, there’s something terribly unjust in that. And I think it resonates with people. It’s the kind of story that you don’t want to read but you’re drawn to.

The Times’ obit section has made news of its own in recent years with the Overlooked project, and trying in general to acknowledge and address its history of overwhelmingly featuring white men. Since we’re seeing now clearly that this crisis is affecting communities of color more than others, is that part of your calculus in how you’re thinking about how to cover these deaths?

We’re trying to be broad. We’re trying to be egalitarian, if that’s the word. Does it change the calculation? I’m not sure. I don’t know yet. We’re certainly conscious of it. The Overlooked project was a reflection of that. That we were conscious that the paper historically hadn’t been writing about people from all walks of life or genders or races. There may have been some ignorance on the part of the paper. Or they weren’t hearing about these deaths. Or they had a different standard of news back then. We’re talking decades going back.

There’s been a corrective kind of attitude toward that. I think we’re more conscious now than maybe 10 years ago of doing more women, doing more racial minorities. I don’t know how this particular pandemic will change that calculation. We’re going to continue to have that kind of consciousness. We still have a mandate to write on the people who’ve made the biggest contributions in society. So that could be scientists and sports stars and actors and presidents and captains of industry and all that. We can’t not do those. But we can also embrace a different range of people.

“I had an email yesterday from a woman whose husband died, a long description of how he had recovered briefly and then had a relapse.” — William McDonald

On high-profile people, are you keeping an eye on the headlines? Did you rush to put together an obit for Tom Hanks? Or Boris Johnson?

That certainly got our attention. Boris Johnson went into ICU, and so we quickly put together an advance obituary just in case. We had our correspondent in London do it. So we were ready on him. Tom Hanks seemed like he was recovering pretty quickly, and it didn’t seem at that point that we had to rush and do an advance on him right away. You’re always making a calculated guess. You don’t know. It’s always a matter of who do you do, who do we wait on. We have so much else to do, and there are so many other people we need to prepare for with in-advance obits. That’s also a huge part of our operation. That’s a whole ’nother story, getting those done. But yeah, when we hear of anyone circulating on the internet, we’ve done a bunch of them in advance. We’re doing a couple right now that we’ve heard of somebody with coronavirus who is not doing well. We had one on John Prine ready.

Has the Times reassigned reporters to cover the range of deaths, beyond the biggest names?

We’ve been given some reinforcements. We have a small department of nine people. We’re doing other obituaries as well, of prominent people, you know, that we can’t not do. So our resources were stretched pretty thin.

One thing that this project has done is excite people, in a morose way. People want to participate. Others in the paper, others around the paper, wanted to participate. And so we’ve gotten contributions in all parts of the newsroom. So that’s been heartening. It’s a moment in history that, you know, as journalists, I think, they want to participate in. It’s been a great help to us.

Is it normally difficult to get people to write obits?

Yes and no. In normal times, it’s more of a struggle. Because first of all, people from other desks are always busy. They always have deadlines; they always have news. They’re covering their beat. So it’s not always easy to get them to drop what they’re doing and do an obituary on somebody. But they do. We get contributions from other parts of the paper, but it’s more about resources. We’re competing against ourselves in some ways, our colleagues, for those resources.

When I see someone has died now, I immediately scan the obit to see if COVID-19 was the cause. Are aware of that phenomenon or that reader tendency, and has it changed how you report cause of deaths at all?

This has now become one of maybe the most newsworthy causes of death. Traditionally the cause of death was secondary. This is now actually, obviously, news. And I hear you. People do search for those causes. Online, we label the people who die of coronavirus. The standing rubric is Those We’ve Lost. Anyone who dies of it now gets that label. There is tremendous reader interest in who exactly is succumbing to this. This is a whole new world for us, in obituaries, to even be doing that kind of thing.

Have you encountered anyone lobbying to have it not mentioned as a cause of death?

I haven’t yet. It could be that someone didn’t tell us. We can only rely on what they tell us. We can’t investigate each death and get a medical examiner’s report. So we do rely on families, and friends, and associates, whoever, to tell us what the cause was. And we rely on them to be truthful. So if they want, if they choose to not mention it, yeah, then we’re not going to know. We’ll be in the dark. They give another underlying cause as the cause. I don’t know of anyone who has asked us not to mention that.

Has 15 years of doing this job prepared you for the pandemic in any way, or how to process it?

Fifteen years of my obituaries job is a long stretch. I’ve enjoyed this job, actually, more than any. But you know, I’ve been a journalist for 30 years. I think basically what prepared me was 30 years of just having a journalistic frame of mind about everything. And going about jobs even when the subject is difficult, whether it’s 9/11 or this. But the difference here is that we’re dealing with something that is around us as well. I’m sitting in my living room at a makeshift desk. This is something happening to us, the people who are actually writing about it and reporting on these deaths. And some of us know people who’ve been affected.

I think there’s a certain level of anxiety or stress that’s been injected into this job that I didn’t feel before, because I could be journalistically removed from it. I have been dealing with people’s deaths for many years. And I’m always going to put on my journalist’s cap and treat them as news. Which is not to say I’m cold and callous, but that’s the way we have to be.

This is obviously a different beast. So I think in a way, yes, it’s put this pandemic in the forefront of my mind almost 24/7. I mean, there’s little relief from it. I get emails all the time. I had an email yesterday from a woman whose husband died. She gave me a long description of how he had died, and how he had recovered briefly and then had a relapse. And she was—it was an emotional email from someone I don’t even know. She was asking us if we would report on his death. It’s right there in front of us, and it’s direct. A friend of mine lost a brother to this. We’re reporting it, but we’re also in the middle of it at the same time. That’s what’s new.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2W9jo0G

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言