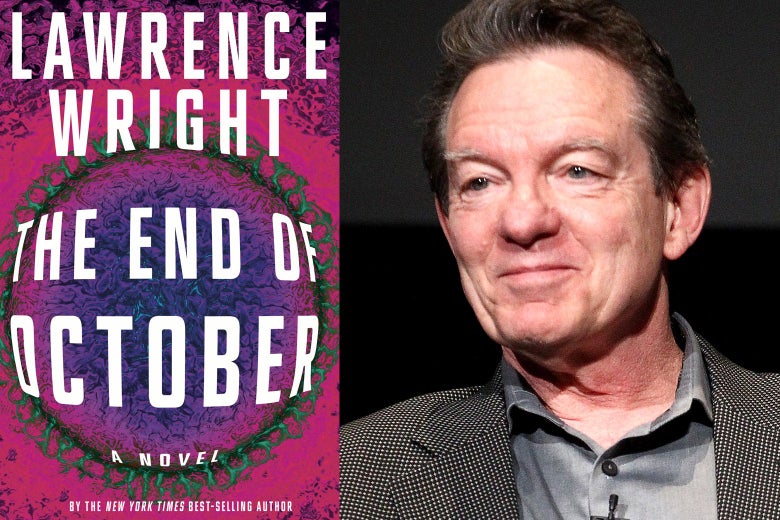

Photo illustration by Slate. Images via Penguin Random House and Tommaso Boddi/Getty Images for Hulu.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

The publication of Lawrence Wright’s The End of October—a thriller about a global pandemic—in the midst of an actual pandemic is either the best possible luck from a marketing standpoint or the worst. Nobody can think about anything beside the COVID-19 virus right now, and Wright is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, a staff writer for the New Yorker, and the author of bestselling books about 9/11 and the Church of Scientology. You can be sure that—even when writing fiction—Wright has done exhaustive research and carefully consulted dozens of experts. We’re all desperate to know how this thing will play out, and he seems eminently qualified to speculate on that. Furthermore, the early chapters of The End of October will strike many readers as uncannily prescient: the quarantines, the resistance to the quarantines drummed up by shadowy forces, the overwhelmed hospitals, the shortages of protective gear and ventilators, the plummeting Dow, the emptied supermarket shelves, and sentences like “Commentators on Fox were applauding the forceful actions of the administration for stopping the disease, citing the much-criticized travel ban.” That lends credibility to Wright’s predictions about what might happen next.

Which makes the rest of the novel utterly terrifying. Wright’s scenario includes a temporary summer reprieve from new cases, followed by a vicious resurgence of his fictional virus—a hemorrhagic fever dubbed Kongoli after the Indonesian prison camp where it is first identified—in the autumn. (The novel is titled after the date its final scenes take place.) A cyberattack on the U.S. compounds the viral carnage, bringing down the Internet and the power grid, setting off chains of explosions on gas lines. There are food shortages, deserted suburbs, dead bodies piling up, gangs of orphaned children, feral dogs roaming the streets, and heavily armed nutjob militias hopped up on conspiracy theories fed to them by Russian operatives.

Wright’s hero, a doctor and CDC official named Henry Parsons, along with his family and colleagues, will suffer such ordeals as hunger, attempted rape, desperate treks through ravaged landscapes, bombardment by Iranian missiles, and of course the deaths of loved ones as civilization crumbles. In Chapter 3, we meet a little old lady who is obviously going to end up being eaten by her cats. Probably this seemed like fodder for informative entertainment as recently as a few months ago, but at the moment it may be more excitement than many readers can take. Zombie apocalypse yarns are fun enough when you’re cozily streaming Netflix on your living room sofa, but it’s another matter once the zombies are scrabbling with their bony fingers on your front door.

There’s a lot of plot in The End of October. In addition to Henry’s adventures in pandemic control, which involve quarantining the entire city of Mecca when an infected cab driver carries the virus to the Hajj and a stint on a nuclear submarine that picks him up after he nearly drowns in the Persian Gulf, chapters are told from the point of view of his wife, Jill, back in Atlanta; his 12-year-old daughter, Helen; and Tildy Nichinsky, a faceless bureaucrat in the Department of Homeland Security with an implacable animosity toward Russia who in the course of the crisis rises to the post of National Security Advisor. The pandemic ignites a smoldering conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran, along with their respective sponsors, the U.S. and Russia. There’s a sinister German biologist and animal rights activist named Jürgen who sports long, platinum-blonde hair and runs a cultic movement called Earth’s Guardians. Richard Clarke—thanked in Wright’s acknowledgements for lending the novel “his persona”—appears as the sort of puppet master who would be played by Sydney Greenstreet in an old movie.

Perhaps Wright means these subplots to illustrate how heads of state get caught up in meaningless geopolitical gamesmanship that distracts them from genuine threats like the Kongoli virus. “If you paid any attention to the role of disease in human affairs,” a scientist lectures Tildy, “you’d know the danger we’re in. We got smug after all the victories over infection in the 20th century. But nature is not a stable force. It evolves, it changes, and it never becomes complacent. We don’t have the time or resources now to do anything but fight this disease.” But it also sometimes feels like the war and terrorism in The End of October is meant to juice the story. Wright first conceived the story several years ago as a screenplay for director Ridley Scott, and back then, car chases in the desert, naval standoffs, and ominous mutterings about Vladimir Putin must have seemed a lot more exciting than sick people and exhausted healthcare workers.

I couldn’t decide if it was exactly the thing I ought to be reading right now, or if it was exactly the wrong thing.

In truth, The End of October is largely an information-delivery system for the history of and bad news about the pandemic threat, something journalists and public health officials—not to mention at least one Hollywood screenwriter—have been warning us about for years. It seems prophetic because Wright, unlike most of the rest of us, was paying attention. Only the oblivious would marvel that the experts are saying the same things now (shelter in place, wear masks) that they said when Wright researched the book, or that people and microbes behave predictably. Using fiction to impart all this makes sense. A thriller probably is a more palatable way to get the message across than the dire alarms sounded by feature journalists, but chances are The End of October would have found only a modest audience had it been published in a COVID-19–free America during the unfolding of an exceptionally divisive presidential campaign.

As a novel, even as a thriller, this book is pretty basic. The characters are rote: noble, self-sacrificing scientists; stalwart, no-nonsense military men and women; spunky 12-year-old girls; shortsighted politicians; Jürgen with his Bond-villain hair; wives who get on the phone and say things like “I need you! Your children need you!” (That’s a direct quote.) The novel has neither the panache of a Lee Child thriller nor the ingenuity of Harlan Coben, although occasionally a minor character stirs to life, like the Indonesian cab driver, whose simple exultation at making his doomed pilgrimage to Mecca is heartrending.

Nevertheless, The End of October scared the shit out of me. I couldn’t decide if it was exactly the thing I ought to be reading right now—and excuse me while I head to Walmart to pick up 50 pounds of lentils and a gun—or if it was exactly the wrong thing. It’s got me side-eyeing my neighbors and wondering if they can be counted on in a pinch. Also, I recently got a cat, and sometimes she looks really hungry.

By Lawrence Wright. Knopf.

Slate is making its coronavirus coverage free for all readers. Subscribe to support our journalism. Start your free trial.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2Y5xy5A

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言