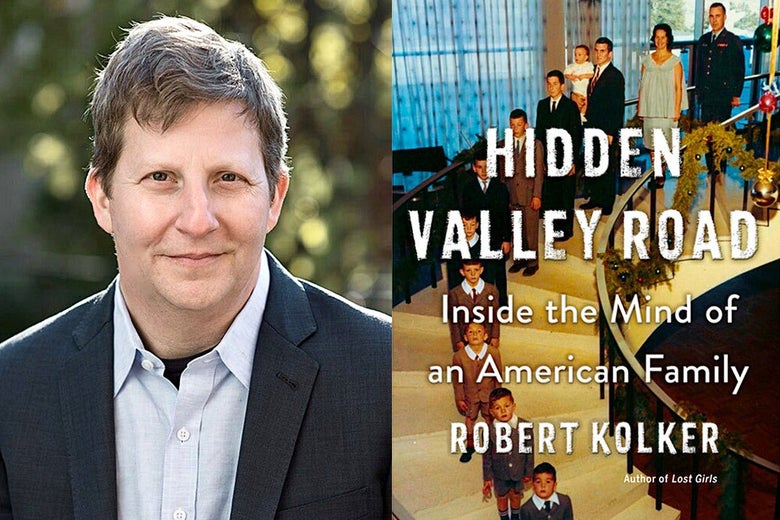

Photo illustration by Slate. Images by Jeff Zorabedian and Penguin Random House.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

The Galvin family of Colorado Springs, Colorado, had many secrets, but the biggest one became increasingly hard to hide as the 12 children of Mimi and Don, a former Air Force officer who headed a regional development agency, grew up. Six of the couple’s 10 sons, born between 1945 and 1960, developed schizophrenia, experiencing delusions and hallucinations. As Robert Kolker writes in Hidden Valley Road, his history of the Galvins and the disease that shaped their lives, “Certainly no researcher had ever encountered six [schizophrenic] brothers in one family—full-blooded siblings with the same parents in common, the same genetic line.”

While this mysterious disorder does run in families, the way it is inherited has long baffled scientists; it doesn’t appear to be passed directly from parent to child. Long after schizophrenia shattered the Galvins’ façade of an ordinary, fun-loving, Catholic clan, doctors seeking to discover more about the illness learned of the family’s extraordinary history and collected their genetic material. The Galvins’ contributions led to significant breakthroughs in understanding which brain functions schizophrenia affects.

What scientists regarded as remarkable, the youngest of the Galvin siblings, Lindsay and Margaret, found frightening. Their older brothers were intensely rivalrous, sometimes violent, and often treated them like toys, or worse. As the brothers pinged between the state mental hospital and the family home, where their mother devoted herself to caring for them, the girls felt neglected and endangered. Yet as adults, the two women maintained their connections to their troubled clan, with Lindsay returning to nurse their ailing mother and help her brothers negotiate the institutional bureaucracies that presided over their lives.

The author of Lost Girls: An Unsolved American Mystery, a celebrated book about a series of unsolved murders in Long Island, Kolker has plenty of experience telling the stories of traumatized families. Lost Girls, the basis of a Netflix film of the same title starring Amy Ryan and Gabriel Byrne, explored the lives of five victims, all sex workers, and their families, as well as the often inept and negligent efforts of the police to find out who killed them.

“I started this book with two questions,” Kolker told me of Hidden Valley Road in a recent phone interview from his home in Brooklyn: “How could all of this happen to one family? And how on earth did that family stay together?” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Laura Miller: How did you find out about the Galvins?

Robert Kolker: My friend and former editor at New York magazine, Jon Gluck, went to high school with Lindsay. One day in 2015 or 2016, Lindsay came through town and met up with Jon. She told him that she and her sister wanted their family’s story told but had decided they didn’t want to write a memoir themselves. They were ready for an independent journalist to take this wherever it was going to take them. Jon thought about me because he’d edited my magazine article about the Long Island case and understood that I wrote about people in crisis and vulnerable sources.

Stigma was a huge problem for this family. They moved to a small town, but they thought of themselves as cultural sophisticates, intelligent and liberal. Yet it was so hard for them to address what was happening to their sons. One reason was the since-debunked psychoanalytic belief in the “schizophrenogenic mother,” a personality type that supposedly caused the illness in her children.

Mimi said that both she and her husband were deeply ashamed and felt they couldn’t open up about what was going on to anyone, not the people who lived next door, not even their closest friends. She didn’t use terms like “schizophrenogenic mother,” but she did say that they were made to feel that they were at fault. To her, that may have been the primary thing. But a deeper factor was that their life felt like a house of cards. If her husband’s prestigious job was in jeopardy because he was talking about having a volatile, mentally ill son at home, that would mean no income to support the other children, and there were a lot of children. And what about that stigma keeping any of them from having any sort of future? I think they were worried about the whole family going down the tubes.

Blame—or responsibility—can be a big issue in family histories. Well, at least it is in my family! When you write such a detailed account of so many interlocking relationships, you can get tangled up in the issue of who’s responsible. The people involved often have strong and conflicting ideas about that. How do you approach that if you’re writing an account that’s basically sympathetic to everyone?

Part of it is to try to understand everyone’s rationale. That way, at the very least, you’re giving everyone a chance to be heard, even if you end up refereeing certain points and deciding certain things had to be the case that other people don’t believe were the case. But I completely get how one person’s version of a family can be different from their sibling’s version. I have two siblings and I’m sure our stories about our family are partially self-serving and partially distorted. The only way to move forward when you’re telling a story about a family with 12 children is to decide that’s going to be a feature, not a bug.

The science part of it was unfamiliar to me. The family part of it, I’d had a little experience because of the five families I wrote about in Lost Girls. In a couple of those families, the narratives were so conflicting between the various family members that I finally realized that I had to acknowledge the ambiguities, otherwise I’d be giving up my job as a writer.

I really love writing about families, and this was a chance to do a multigenerational saga. It made me think of East of Eden or The Corrections. What a chance to write about someone in the second generation doing something and you know it has echoes in the previous generation because you’ve written about the mother too.

I notice that you just cited two comparisons that are fictional. What a lot of people want from a nonfiction writer is someone to adjudicate or make a case for what the definitive truth is. That was a challenge with Lost Girls, because no one knows who the killer is. You couldn’t solve that mystery, and readers expect true crime books to do that.

I’m comfortable with that. My role isn’t to be an investigative reporter but to be an explanatory reporter, to get everybody’s memories and rationales and points of view. What I’ve learned is that readers are more invested that way. They get it. They understand what’s known and not known.

As with Lost Girls, once again you have a story where there isn’t a definitive answer: Despite what researchers have learned from the Galvins’ DNA, we still don’t really know what causes schizophrenia or even, really, what it is. In such cases, is finding a central character or characters the key to deciding if you have a book or not?

I think it is. I’m not primarily an ideas writer. And I’m not primarily a stylist or a pundit. And while I’ve done investigative reporting, I don’t think I’m the world’s greatest investigative reporter. I connect with a story by writing about the people. Telling the people’s stories helps me arrive at the ideas I want to get across and it motivates me to research the science and the background. It makes me a better investigator to walk in the footsteps of the people in the book.

With Lost Girls, hopefully readers come away thinking that police work is not like SVU. It just isn’t. Things get screwed up all the time. There’s incompetence, and there’s corruption, but there’s also just life and chaos and murderers who get away with it. That’s just the way the world is. And you come away from it perhaps a little wiser.

In the same way, we tend to think of medical progress as this nonstop forward march. In fact, it’s more complex and weird than that. It goes in many directions. There’s tunnel vision and groupthink, and there’s politics and sexism and any number of things that hinder progress. To me that’s a satisfying story to write because it feels more real.

One flabbergasting stalemate you write about has to do with Dr. Lynn DeLisi, who collected a significant dataset about families with multiple cases of schizophrenia. She gathered that data while working for a pharmaceutical company that then got bought by Pfizer, and they were not interested in continuing her project. But they actually owned all that data, so it couldn’t really be used for many years. It was in mothballs.

That was because there isn’t a lot of interest in developing drugs for schizophrenia. It seems so hopeless and the victims of the disease can’t advocate for themselves and it’s so expensive and risky to test. You can’t test it on a rat because rats don’t get schizophrenia. You have to test it on people. That makes it much harder to get off the ground.

And yet, it’s a surprisingly common and devastating condition. The fact that there isn’t much initiative to find better drugs to treat it is shocking.

I was at a conference last fall and one of the big epidemiologists who measures schizophrenia around the world said, “Everyone asks why, if we can put a man on the moon, we can’t cure this disease, but the problem is that curing this disease is actually harder than putting a man on the moon.” So that’s part of the problem too. And finally, there’s that stigma, which still exists.

There haven’t been huge recent breakthroughs in understanding or treating schizophrenia, but could you summarize where we are now?

We know that the medications being used right now, like Thorazine, might be decent in managing the symptoms of the illness, but it’s nothing like a cure. In fact, there’s evidence that the patients who take them have the same chance of relapsing or experiencing psychosis as patients who spend their lives not taking the medications, which was surprising to me.

One of your sources makes a great analogy to the history of the medical profession’s understanding of fever. “Fever” was once regarded as an illness in itself, whereas now we understand that it’s a symptom of many illnesses. You can take medication that will control a fever, but it will not treat the actual disease causing it. The same is true of drugs like Thorazine and schizophrenia; they affect only the symptoms.

Although schizophrenia is not really a disease, but a collection of symptoms that have been bundled together under one name in the DSM, and human biology did not evolve to fit the DSM. It’s true that those symptoms might mean something entirely different from what we think they mean, and generations from now, we’ll see that they’re really pointing to something else.

Just speaking practically now, we know that early intervention can work wonders. Instead of waiting until the person turns 25 and has had four psychotic breaks, getting to that teenager when they’re starting to hear voices, getting past that stigma, can be very helpful and can keep that person from descending into acute mental illness. That’s really encouraging.

Meanwhile, the prospect of pinpointing the genetic sources seems to have gone bust.

The genetic part of it has been really disappointing. We really thought 20 years ago that as soon as the human genome was sequenced we were going to knock out any number of complicated diseases. We thought we’d just look at the genes of someone who has a disease, see where the problem genes are, fix those genes and be done in time for dinner. That didn’t happen for any number of diseases, including schizophrenia, where they found one gene and then another and then another and now they have over 100. Each of those irregularities they’ve found only add a small probability that you’ll get the illness.

It’s understood that this is a developmental disorder. It’s not like something happens to you in adolescence and you become mentally ill. It’s something you’re vulnerable to developing from the time you’re in utero. There’s something genetic that sets you up to be vulnerable, but at the same time there’s something in the environment that triggers it. That’s led to theories about everything from pot use to cat litter: Everyone’s looking for the trigger.

You also write about the promise of prenatal choline supplements.

Robert Freedman of the University of Colorado, who first met the Galvin family in the 1980s, is the one behind the research into choline that’s continuing now. Kids who first got it when they were in utero are 4 or 5 years old now. Things look good for them, but we won’t know anything for a long time. The FDA in 2015 recommended that pregnant women take choline supplements for “better brain health,” although I don’t think it’s made it into the multisupplement prenatal tablets yet, but perhaps it will. Meanwhile, Freedman is trying to spread the word on his own, but there isn’t anything conclusive yet. Choline hits a brain receptor that’s involved with nicotine. This has some relationship to the stereotype of people with schizophrenia being chain smokers. Smoking tends to calm them down and help them focus. In utero you don’t need a cigarette or even actual nicotine to strengthen that area of the brain. You can instead take something very safe: choline. The challenge in this book was not to oversell these advances as cures, though.

A powerful element of this book is that it does justice to the devastation that schizophrenia causes in the family members who aren’t ill themselves. The sick brothers are suffering, and their parents are suffering in trying to help them, but as a result the well siblings feel neglected by their parents and often abused by the sick ones.

If you’re the well sibling in a family where there are troubled siblings, you feel like you can’t admit to any problems. First of all, your problems won’t be appreciated—or at least in this family they weren’t. The mother would say, “You think you’ve got problems?” They felt neglect and abandonment and that the sick children had the parents’ favor. The siblings of people with schizophrenia often worry that if they show the slightest abnormality, they might get sent to the mental hospital. In the Galvin family, everyone was wondering who it would hit next, so the last thing you want to be is the person with any kind of problem.

This is the second book in which you’ve done an amazing job of writing at length about very sensitive personal experiences. How do you approach interviewing someone about this kind of painful, intimate family material?

When it comes to talking about the most difficult parts of someone’s life, it’s possible—and I would say, quite likely—that the person has been rehearsing in their mind the very things they’d say in an interview situation for a long, long time. So it’s important not to walk in firing a million questions. Let them say the things that are on their mind in any order they want to say them. Make sure that they know they’re being heard and listened to, even if only some of that winds up being something you act on. It’s important to hear where they’re coming from before you do anything else. Another tip is to assemble a chronology. The better questions come up once you understand the chronology.

Can you give me an example?

Everybody said that Peter had his first psychotic break at school at age 14, sometime after the huge calamity of the family, which was the suicide of a brother who at the same time killed his girlfriend. Everybody also said that Don, the father, had a stroke around the same time too. But only in talking to people and getting the chronology down did I learn that Peter was actually watching when his father had the stroke and that three weeks after that is when he had that first psychotic break. That made sense in a way the family itself had not considered.

Have you had sources object to what you’ve written about them?

Certainly, and quite often it’s because I appear to be giving more weight to other perspectives. There was a mother in Lost Girls who told the story of how her daughter got torn from her control in one way, and then four or five other people in the family told it a different way. So I had to referee that in writing. She came away OK with the book as a whole but upset that her family got to say all those things about her in a book.

What was the most surprising thing for you about the Galvins’ story?

I started the book with two questions: How could all of this happen to one family and how on earth did that family stay together? Why didn’t Lindsay or Margaret get out of town and never come back? I don’t think I’ve ever talked to someone who’d been the victim of brutal abuse and had mental illness be so terrifying to them as a child, someone who’d sat and watched while their parents made several errors so that they ended up being neglected for the sake of others, and then found a way through it to reevaluate those parents years later, to even forgive aspects of it. That bowled me over. I was really stunned, and I’ve been working the crime beat for a while, so not a lot stuns me.

By Robert Kolker. Doubleday.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/34kZJOY

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言