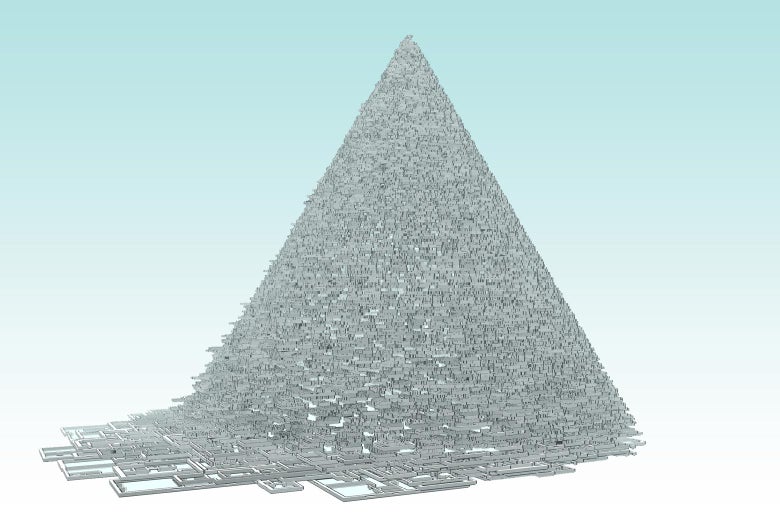

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, New York Apartment, 2020. Screenshot.

As people across the country hunker down in an effort to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, many institutions, like museums and theaters, have shut their doors to the public—but some still offer virtual tours or online exhibitions for those bored out of their mind at home. New York Apartment, by artists Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, wasn’t created with quarantine in mind, but the project has taken on a new resonance in our current moment of isolation. Brain and Lavigne compiled real listings for properties across the city to create a website advertising “a fictitious New York City apartment for sale that covers more than 300 million square feet and spans the five boroughs,” according to the website for the Whitney Museum of American Art, where the exhibition currently resides. As with any real estate listing, it displays the number of bedrooms and bathrooms, an array of amenities, and the price tag: $43.9 billion.

Alongside the thousands of photos of apartments across the city and hundreds of inane questions posed by advertisers (“Are you ready for the next level? Are you ready to fall in love?”) Brain and Lavigne also created four different 3D virtual tours of floorplans that viewers can click through. Slate spoke to Brain and Lavigne by phone to find out more about the project’s design, what they learned from putting it together, and whether the pandemic has made them see their work in a new light. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rachelle Hampton: Where did the idea for New York Apartment come from?

Tega Brain: I had to move and was looking for an apartment. Most New Yorkers have to do that every year. In the process, you spend a lot of time on real estate sites. Sam decided to help me and try to scrape information off every real estate listing in New York City.

Sam Lavigne: You can learn a lot about a dataset based on how easily you’re able to access it. A lot of what’s going on with real estate websites is that the data itself, about what is for sale or what is for rent, is a kind of commodity. They try to make it difficult to access. I was really interested in that. Initially this project was coming up with an alternative interface for exploring that data, and yes, definitely to help Tega find something. In a way, it’s a lot easier to try to figure out what’s going on if you are able to download everything and sort through it the way you would look through an Excel table on your own computer.

A lot of what we do, especially what I do, is use this technique called web scraping, where instead of looking at a website with my browser, I run a program that goes through a website and just basically downloads a copy of the whole thing for me. Then once you have that, that’s data that you can explore in lots of different ways.

Can you tell me more about that?

Lavigne: The easiest way to explain this is you could imagine going to like Trulia.com or something, and you click on the “for sale” thing on the front page and type in “Manhattan” or “Brooklyn” or whatever. Then you click on literally every single listing and you save and download them, or you have an Excel spreadsheet open and you’ve got a column for price and a column for square footage and a column for bedrooms, and you just copy and paste for every single listing.

That’s if you were doing it manually. The difference is that we just wrote a computer program to do that instead. That’s the square footage, the bedrooms, the year it was built, the neighborhood, the number of bathrooms. We downloaded every single image from all of those listings also, and all of the descriptions. They typically have very flowery descriptions.

Brain: We also downloaded, in that same process, all of the floor plans. We used a program to extrude them into a 3D form and then created those virtual sort of assemblages of all of the apartments to form this vast structure that you can fly around and navigate.

I’m curious how y’all chose how to visualize this insane amount of data into four different possible floor plans for all the apartments: “two different vertical towers, a flat landscape, and a pyramid.”

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, New York Apartment, 2020. Screenshot.

Lavigne: I mean, the tower was obvious. I realized this after the fact, but I think it’s inspired by like the Talking Heads a little bit, in the way that we’re playing with language and they sing about the suburbs and stuff.

Brain: About home and what counts as home.

Lavigne: Then it’s inspired a bit by the J.G. Ballard novel High-Rise, where all the rich people live on the top and all the poor people live on the bottom and there’s a class structure inside of the architecture of the high-rise.

Brain: We often were saying that with this project, our philosophy was to include all of the experimentation rather than doing a sort of curatorial cull, which is often a part of doing these generated code-based projects.

Lavigne: There’s also a short story called “Quadraturin” by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky. The plot is basically that they all live in tiny apartments, and someone comes by and offers to sell [the protagonist] this cream and he can rub it on the walls of his apartment, and it will make his apartment bigger. It’s this embiggening cream, but then he gets greedy and he does it too much and then the walls expand infinitely outwards and he’s trapped forever in a vast empty space.

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, New York Apartment, 2020. Screenshot.

It sounds like this project started with a very practical purpose in mind. When did you realize that it could become something more than an Excel spreadsheet to help you apartment-hunt?

Lavigne: Obviously, we all know that housing is a commodity, right? That’s not a big secret or anything, but [the project] reveals the minutia of how housing is a commodity and all the ways that it is sold to us. A lot of it is just the descriptions, the repetition, the way that certain things are staged. The thing that we have been thinking a lot about is housing as a human right.

Brain: Along those lines, we started getting really interested in, like, what if we thought about housing in New York as these commons, where rather than thinking about individual ownership of certain little patches of it, what if we thought about real estate in New York as a collective. Then how does that help us think about how the world could be different?

That idea of a commons is interesting in this current moment, since we’re all being asked to isolate for the greater good. Has anything about the pandemic made you look at your project in a different light?

Lavigne: First of all, yeah, what it does is highlight the insane inequality in the city. The whole project is about housing that’s for sale. Most people can’t afford to buy a house in New York. That immediately is inaccessible to most people.

Brain: But I think the more out of reach it is, the more that people obsess over those websites.

Lavigne: Right, exactly. Then secondarily, even if you’re lucky enough to be able to afford a house, you still can’t afford almost anything that is available. You’re talking about the smallest possible space. That’s one thing. Who is in the big places and who’s in the little ones? You know what it’s like in New York. You get a shoebox, and you’re grateful for it. That’s OK, too, in a way, but some people have access to this vast quantity of space, and they don’t need to have it.

The other thing is, of course, right now we’re looking at a huge homeless population that needs housing, and that’s being exacerbated by the pandemic. We’re also looking at a situation where there’s going to be a huge need for hospitals, more room for sick beds and stuff. I think there’s just a tremendous amount of empty rooms in the city.

Brain: When housing does become a commodity, then it becomes an investment, and then it’s no longer tied to actual need. It’s tied to speculation. We’ve been talking a lot about if there’s a way to identify empty apartments or empty spaces through this dataset to highlight that. That’s something we’ve been thinking about in this current moment.

Was there anything that surprised you in compiling all this data?

Brain: You sort of innately know it if you’ve spent enough time on these sites, but there are two types of photography—well, actually three. There’s the staged real estate photography, where someone has obviously paid a high-end real estate agent to come in and put in fake staged furniture to make their apartment look the best. There’s people who just photograph their apartments as they are. I guess those are the people who’ve got less access to resources and are just wanting to sell. Then there’s also this category of images where people put composites of virtual furniture into the spaces. You get this very weird surreal feeling, because it’s not perfect. You start to notice these different tactics that are being used within the real estate industry to sell a property. The dream they’re selling becomes really clear when you start to read through the whole dataset.

We started to then notice certain obsessions within this market as well. For example, marble, stainless steel, hardwood floors, all of these symbols or ideals when it comes to interiors in apartments. Again, funny, because most of us are not in a position where we can even have those tastes.

What’s the weirdest feature or description that you came across?

Lavigne: One thing that I noticed is this word prewar. I kept seeing the word prewar, referencing a period of architecture. That was striking to me just because of the poetics of the word prewar.

Brain: I’ve been collecting photos from the site of people who didn’t bother to make their beds before they photographed their apartment.

Lavigne: Solidarity with those people. You know what I mean? I’m totally into that.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2UZDeuy

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言