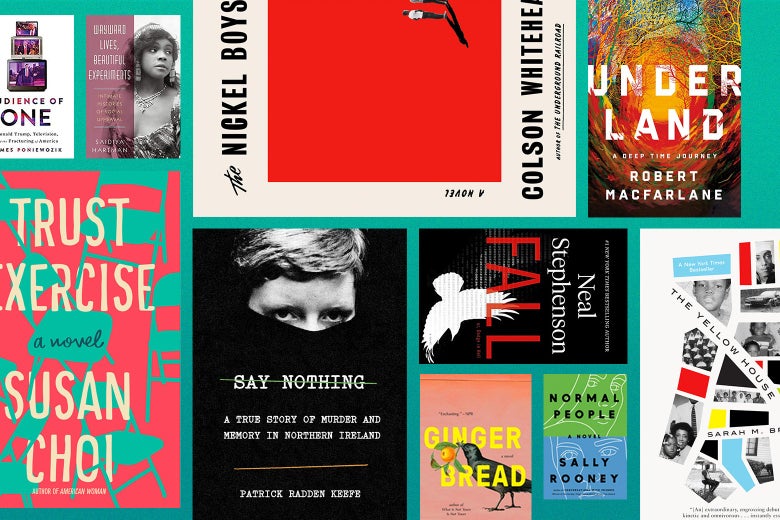

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Liveright, Norton, Doubleday, Henry Holt, William Morrow, Riverhead, Hogarth, and Grove.

FICTION

This wily novel about a group of students at a performing arts high school begins as your basic literary coming-of-age story of love gone wrong, full of overwrought adolescent sex and angst. Is it—just a little bit—bad? Yes! Intentionally so. Suddenly another narrator busts in, determined to take over the book and tell what really happened and, while she’s at it, engineer an elaborate revenge on all those who have wronged her. And yet she’s not telling the full truth either. Choi, who has written novels based on historical figures like Patty Hearst and Wen Ho Lee, is fascinated by what stories conceal as well as what they reveal, and the astute reader will recognize that Trust Exercise is a kind of murder mystery; the only way to get to the bottom of it is not to trust any of them.

By Susan Choi. Henry Holt.

The Lee women—Margot; Margot’s daughter, Harriet; and Harriet’s schoolgirl daughter, Perdita—live in London, but they come from the island nation of Druhástrana. Harriet’s story of her early life in this “alleged nation-state of indeterminable geographic location” is a tale of hardscrabble peasant farm life and a populace mulishly determined to turn its back on the world, expelling confusing foreigners so the Druhástranians can “keep things simple and concentrate on upholding financial inequality.” The one thing Harriet has brought from her homeland is the recipe of the national treat, gingerbread, a baked good so potent and addictive it’s like “a square meal and a good night’s sleep and a long, blood‐spattered howl at the moon rolled into one.” Gingerbread is Oyeyemi’s witty, modern-fairy-tale take on her own homeland, the United Kingdom (she is a Briton of Nigerian descent), and as delicious as the stuff it’s named after.

By Helen Oyeyemi. Riverhead.

Marianne and Connell are teenagers living in a provincial Irish town. He’s cool and she isn’t, but they have a secret romance anyway. Later, in college, their social status is reversed, and they continue a rocky, ambivalent affair. There’s no way any plot synopsis can do justice to how engaging Rooney makes this rudimentary premise. There’s nothing fancy about Rooney’s style either, yet this novel, once it gets its hooks in you, is almost impossible to set down. Normal People is about class, Irishness, youth, and life in the early 21st century, but mostly it’s a tender, bruised meditation on how two people can keep miring themselves in misery even when happiness is within their reach. It does what the novel has done since its birth and what it has always done best, which is to tell a story about how people decide whom to love and what they do about it once they’ve decided.

By Sally Rooney. Hogarth.

I read (or merely began) so many decent novels this year that were well-written and well-meaning in their efforts to tell me important things that I already knew. What I almost never encountered was surprise, a quality that has long been Stephenson’s forte. This engulfing tome begins as a story of corporate and family intrigue involving the disposition of Dodge, a deceased game designer who forgot to change the part in his will asking that he be preserved after his death using the best technology available. Along the way, the singularity—in which the human and the digital merge—becomes a reality. What does it mean to “live” without a body? I won’t spoil Stephenson’s answer, but suffice to say that my mind was happily blown at several points in this endlessly entertaining novel.

By Neal Stephenson. William Morrow.

Elwood Curtis is a promising high school graduate in early ’60s Florida when he makes the mistake of hitching a ride to his first college classes with a car thief. A moral stickler who once obsessively listened to an LP of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches, Elwood gets tossed into Nickel, a brutal reform school closely based on a historical institution. A modern-day Candide, Elwood confronts a regime of arbitrary cruelty, racism, and unfathomable alliances. His guide to this purgatory is Turner, a cynical loner who insists that “in here and out there are the same, but in here no one has to act fake anymore.” At the heart of this novel is the conversation between these two boys about whether there’s any way toward a better, more just world: Elwood insists it’s possible; Turner believes Elwood’s kidding himself, to a degree that might be suicidal. It’s a debate that doesn’t reach a resolution until Whitehead’s ingeniously low-key twist ending.

By Colson Whitehead. Doubleday.

NONFICTION

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom Broom’s memoir is a family saga and a history of the historyless, the story of the neighborhood in East New Orleans where her mother bought a modest shotgun house in 1961. The house became the center of Broom’s family life, a web of indelible personalities—many of them not blood relations—drawn by Broom with a shimmering grace. Broom herself doesn’t appear until over 100 pages in, but her relatives are like the characters in a Russian novel: some comic, some tragic, some enigmatic, some exasperating—all handled with great love and zero sentimentality. Their company never gets old. The men tend to work at NASA, although one becomes a chef and another a crack addict. The women are cagey, particularly about the more scandalous aspects of their past, and proud, which makes the deterioration of the yellow house all the more painful; once the setting for parties, its interior becomes a family secret to which guests are never invited. Broom herself is a journalist who worked in Burundi and lived in Harlem, where in 2005 she watched the destruction of her neighborhood by Hurricane Katrina from afar. The family scattered across the country after that, but Broom herself came back, and while the yellow house is long gone, it lives again in this book.

By Sarah M. Broom. Grove.

In this highly original work, Hartman spins archival straw into gold, imagining the lives of rebellious young black women in 20th century American cities as lived between the sketchy evidence of documentary photos, newspaper items, and police reports. Her subjects were “sexual modernists, free lovers, radicals and anarchists.” They chose single motherhood, childlessness, female lovers. They dressed as men and lived it up in dance halls, grasping every last scrap of freedom the city offered them, making “a way out of no way.” They include an actress who settled down in Harlem with a female cousin of Oscar Wilde, a self-made millionaire, and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells. But Hartman is most spellbinding when writing about anonymous figures: a young girl photographed nude by Thomas Eakins, a figure glimpsed in a picture meant to document the squalor of a Philadelphia street, women picked up on dubious prostitution charges who flicker in and out of court records. She can conjure the worlds these women inhabited with an uncanny vividness and make their lives seem more real than official history.

By Saidiya Hartman. Norton.

In 1972, masked men and women knocked at the Belfast flat where Jean McConville, a young widow, lived with her 10 children. The shadowy figures took Jean away, leaving her kids to fend for themselves, nearly starving in a community that seemed inhumanely indifferent to their fate. Jean was never seen again, presumably another casualty of the Troubles, a period of civil unrest between militant Irish republican Catholics and Northern Ireland’s Protestants and the British forces who supported them. Keefe’s riveting book is both mystery and history, full of characters like the Price sisters, a pair of stylish and merciless revolutionaries; Gerry Adams, the canny insurgent-turned-politician who denies any role in McConville’s disappearance; and the sinister brigadier Frank Kitson, who employed interrogation techniques he learned during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya against the IRA. Most of all, it is the story of McConville’s children, who, facing a culture that demanded silence, refused to forget about their mother and never stopped calling for her murderers to be unmasked.

By Patrick Radden Keefe. Doubleday.

Macfarlane’s uncategorizable work is a fusion of nature and travel writing combined with history and science and linguistics. He’s written—ravishingly—about mountains and roads and place names, but with Underland, for the first time, he focuses on the worlds beneath the earth’s surface. What he finds there is fear—his stories about spelunkers trapped in caves and crevices are nightmare-inducing—and wonder. A mycologist named Merlin teaches him about the vast networks of fungi that extend beneath the forest floor, perhaps the largest of living things and a conduit through which trees communicate with each other. He ventures into a limestone labyrinth to find a subterranean landscape of river, cliffs, and black sand dunes. He pokes his nose into barrows and catacombs and tombs. The underland is where human beings investigate dark matter and bury our nuclear waste, where we have imagined the kingdom of the dead and painted our first works of art. In Macfarlane this realm has finally found the writer who can do it justice.

By Robert Macfarlane. Norton.

There are dozens of ways to interpret the election of Donald Trump: a revolt against the postindustrial economy, part of a rising global tide of populist nationalism, racist backlash. But none seems as apt as Poniewozik’s observation that Trump is a creature of television, that he “achieved symbiosis with the medium. Its impulses were his impulses; its appetites were his appetites; its mentality was his mentality.” Sure, to a hammer everything looks like a nail (Poniewozik writes about TV for the New York Times), but while Trump is manifestly incapable of governing, he always knows how to entertain: He drums up conflict, foments chaos, barks insults, and concocts boogeymen. From the era of prestige cable, Trump learned, in Poniewozik’s words, that you can keep “the audience on the side of the antihero by convincing them that his enemies were even worse,” becoming a master of gambits that seem idiotic and even self-destructive but that actually work. To be honest, the shrewd, witty Audience of One is more than a little frightening, but it also—a bit like its subject—puts on a helluva show.

By James Poniewozik. Liveright.

Check out the best books of 2019 according to Slate’s books editor.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2RhdQjF

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言