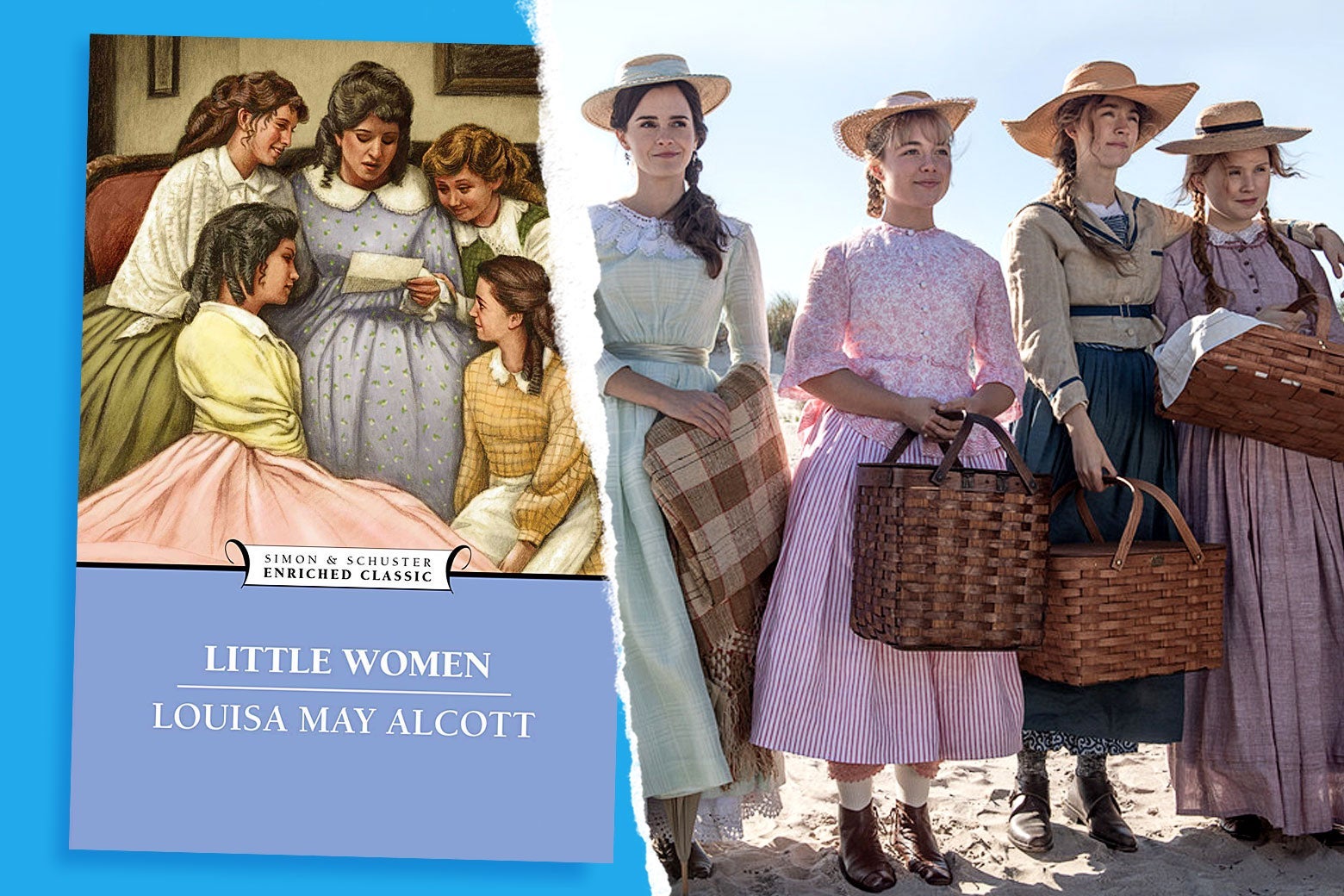

Photo illustration by Slate. Images by Simon & Schuster and Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Little Women has been adapted so many times over the years that certain images have become cemented in the public imagination: the family gathered around a letter from Father at Christmastime, the burnt manuscript, Amy falling through the ice, Jo cutting her hair to pay for Marmee’s journey. Greta Gerwig’s new Little Women movie contains all of these requisite scenes, but it reimagines the story as a whole by turning it into a poioumenon, a work of art about its own making, further blurring the lines between author Louisa May Alcott and her semi-autobiographical heroine, Jo March. Gerwig, who wrote as well as directed this latest adaptation, begins not with the familiar “Christmas won’t be Christmas without presents,” but seven years later, cutting back and forth between parallel timelines.

One timeline covers that more familiar first half of Little Women, which sees the March girls growing up in Concord, Massachusetts, as their father serves in the Union Army. (True to the book, the movie remains zoomed in on the March family rather than giving us the broader context of the Civil War, though Gerwig does sprinkle in a bit of explicit political commentary.) The other timeline covers the less-trod ground of the grown-up sisters on their divergent paths: Meg (Emma Watson) adjusting to married life, Jo (Saorise Ronan) moving to New York and pursuing her writing, Beth (Eliza Scanlen) growing ill once more, and Amy (Florence Pugh) traveling through Europe with their aunt (Meryl Streep).

The result is both faithful to Alcott’s text and wonderfully new, and Gerwig’s adaptation is as radical for how it portrays the lesser-known parts of Little Women as it is for (maybe) changing the ending. Much of the dialogue in the movie is lifted directly from the novel, but the actors often talk over each other, giving it a more natural feel, and Gerwig has both added her own flourishes and borrowed lines from Alcott’s other works. (Still other lines are taken from the Alcott family’s letters: Marmee’s observation that “there are some natures too noble to curb and too lofty to bend” is the result of Laura Dern’s research on Abigail May Alcott, Louisa’s mother.)

Below, we’ve rounded up some of Gerwig’s biggest departures from Alcott’s original text—as well as some aspects that are surprisingly faithful.

MegThe eldest March child often draws the short straw when Alcott’s novel is condensed to fit a two-hour runtime, as filmmakers tend to focus on her more obviously interesting sisters—even Beth at least gets the distinction of a tragic death. Gerwig’s adaptation includes Meg’s visit with the Moffats, where she must contend with her family’s relative poverty compared to her richer friends. But it expedites her courtship with tutor John Brooke, which is a more drawn-out ordeal in the book because Brooke is poor and Meg is too young to marry.

Laurie also meddles in their budding relationship by writing a prank letter in which Brooke confesses his feelings to Meg. When Brooke eventually admits those feelings are real, Meg rejects him, only changing her mind after Aunt March forbids the match, forcing Meg to realize how much she does love Brooke after all. Alas, there’s no time for such Austen-ian confrontations in Gerwig’s movie—only a brief lecture from a tutting Streep after they’re already married—and Meg and Brooke’s romance is confined to making goo-goo eyes at each other.

That said, Gerwig does give Meg a chance to make the case for her own relevance. “Just because my dreams are different from yours doesn’t mean they’re unimportant,” she tells the more ambitious Jo. The movie also offers a rare on-screen glimpse of Meg’s bumpy adjustment to married life and motherhood with an incident taken directly from Little Women’s pages. The first time Meg appears on screen, we see her, egged on by a rich friend, buying a length of expensive silk. This leads to a difficult conversation with her husband about their finances, which is resolved when Meg sells the silk to Sallie. (Gerwig adds an O. Henry–worthy twist by having Brooke tell Meg to have a dress made from the silk after all, only for her to respond that she’s already sold it so he can buy a new coat for winter.)

That’s just a small taste of Meg and Brooke’s domestic squabbles in the novel, which range from expectations about keeping house to disagreements about how they should discipline their twins. Though there’s plenty of moralizing from Marmee about how Meg is neglecting her husband, Alcott herself seems largely sympathetic to the eldest March sister, who she describes as “nervous and worn out with watching and worry, and in that unreasonable frame of mind which the best of mothers occasionally experience when domestic cares oppress them.”

Though Gerwig’s movie can only gesture at this dynamic and makes Brooke a more modern partner than he is on the page, it’s refreshing to see a version of Little Women in which Meg’s story doesn’t just end with happily ever after.

JoAt times, Gerwig blurs the lines between Jo March and the real Louisa May Alcott to the point where it’s hard to tell which one we’re watching: The movie begins with a copy of Little Women with Alcott’s name on the cover; by its end, the author has changed to Jo. Though Jo does give up her more salacious stories to write more wholesome fare in Alcott’s book, she never explicitly writes a book called Little Women.

Jo’s romantic life is even more different in the movie. The Professor Bhaer of Gerwig’s Little Women is almost unrecognizable from the one in Alcott’s novel. Though he lives in the same boarding house as Jo in New York and disapproves of her work, his motivations have been totally changed. The Bhaer of the book takes a passive-aggressive approach, objecting to Jo’s stories on moral grounds and then shaming Jo for writing them by pretending he doesn’t know she’s the author.

Gerwig’s version of Bhaer, played by Louis Garrel, challenges her rather than censures her, telling her outright he doesn’t like the stories, but adding that he thinks she’s talented and needs someone to take her seriously enough to be blunt. Though Jo initially dismisses his comments as those of a critic, this Bhaer is more of an editor. He’s certainly more of an editor than Jo’s actual editor, Henry Dashwood, who doesn’t realize the value of her less sordid writing until his daughters get hold of it—another detail Gerwig borrows from the real Alcott’s career.

As for whether or not Bhaer and Jo end up together in the movie, as they do in the book, that’s a matter of debate.

BethLike the fictional Beth March, Alcott’s sister real-life Lizzie contracted scarlet fever from a neighboring immigrant family. She recovered but still died young, though her exact cause of death is not exactly clear—it has been speculated by modern scholars that it may even have been the result of an eating disorder or mental illness. There’s also evidence that Lizzie was not as serene about her mortality as her fictional counterpart in Little Women. Gerwig doesn’t pursue any of these avenues in her depiction of Beth, taking a traditional approach to the character: Beth’s illness is specifically attributed to her weakened heart, and she bears it as angelically as she does in the book.

Though Gerwig doesn’t save Beth from dying, she does spare her from two other, smaller tragedies from the novel: Her canary Pip doesn’t starve to death, nor does the Hummel baby die from scarlet fever in her lap. The movie additionally doesn’t touch on Jo’s (incorrect) suspicion that Beth might be lovesick and pining for Laurie.

AmyRather than casting two actors as Amy like the 1994 adaptation, Gerwig’s Little Women keeps 23-year-old Florence Pugh as Amy throughout the movie, using a thick set of bangs to distinguish her younger self in flashbacks. (The Irishman could learn a thing or two.) Young Amy is punished in the movie for drawing an unflattering caricature of her teacher—after initially refusing to draw one of Abraham Lincoln and rejecting a classmate’s argument that the South should’ve been allowed to “keep their labor,” one of Gerwig’s nods to the wider world outside the March home. In the book, it’s a different offense that leads to Amy’s punishment: the possession of pickled limes, which have been banned from the schoolhouse.

As is the case in many other adaptations, grown-up Amy travels to Europe with Aunt March on the trip that Jo wanted to take, but in the book, she actually goes with the girls’ Aunt Carrol, as well as her husband and daughter. (Aunt March is also supposed to be the girls’ great aunt, not their father’s sister, as is the case in Gerwig’s version.) Aunt Carrol is otherwise forgettable, so it makes sense to eliminate her from the movie and give her storyline to Aunt March, both for the sake of efficiency and because who doesn’t want to hear Meryl Streep make snooty pronouncements about the French?

Amy is a much more sympathetic figure in Gerwig’s version than in others, where the story’s lack of a villain means she sometimes falls into the role by default. By beginning with the sisters as adults and establishing Amy and Laurie’s dynamic early on, Gerwig makes them, not the less-suited Jo and Laurie, the couple to root for. We also get a look at Amy’s artistic ambitions and why she abandons them in favor of an advantageous marriage—a prospect lent new importance by Meg’s unhappiness and Aunt March’s explicit instruction that she marry well to save her family. Though Gerwig wrote the “marriage is an economic proposition” speech, Amy’s line about being “great or nothing” is all Alcott.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2StJaww

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言