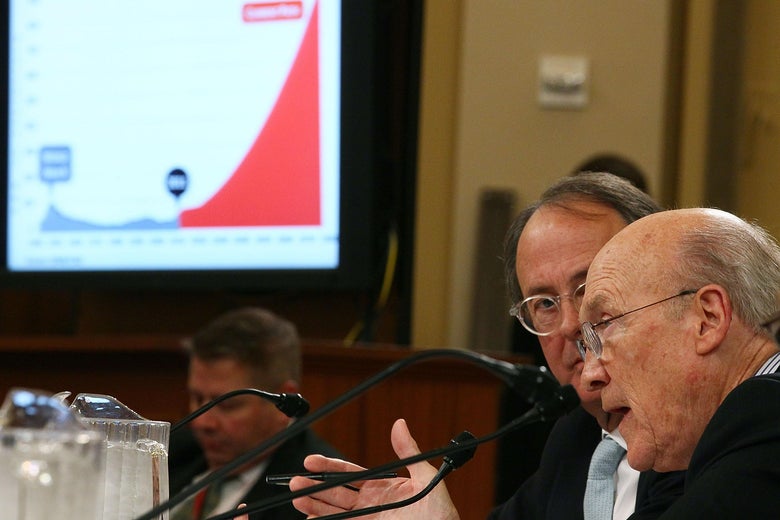

Co-chairmen of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, former Sen. Alan Simpson, and Erskine Bowles, symbols of the economic folly of the 2010s.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Economically, the 2010s were a slow-motion tragedy—a needlessly wasted decade during which bad policy decisions and cynical politics condemned millions to unnecessary joblessness and hardship. From the White House to Congress to the Fed, there were failures in every corner of the government that combined to turn a crisis into a lingering ordeal.

It began in the catastrophic aftermath of the Great Recession. Depending which economic indicator you look at, the country’s recovery from that disaster was either slow or extremely slow. The official unemployment rate only returned to its pre-crisis level in 2017. The share of Americans aged 25 to 54 with a job, which many economists now believe is a better barometer for the labor market, only completed its rebound this past October, almost a full ten years after bottoming out.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

It never should have taken this long for the U.S. to recuperate. The reasons it did have everything to do with choices people in power made along the way.

The Obama administration’s stimulus bill, which was expected to cost $775 billion when it passed, was a historic effort to rescue the economy from collapse and yet still too small for the task. This was known at the time. In January 2009, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote that administration’s plan was “unlikely to close more than half of the looming output gap, and could easily end up doing less than a third of the job.” But inside the White House, people were worried that a larger plan wouldn’t be able to squeak through Congress, and that anything approaching the symbolically important $1 trillion mark would be dead on arrival. Years later, Christina Romer, the chair of Obama’s Counsel of Economic Advisers, explained that when she pushed for a larger stimulus—“I did raise with the president-elect $800 billion is as big as we think it just has to be, but if you went a trillion or $1.2 trillion, that would be even better”—she was told it wasn’t politically doable.

The politicos might have been right about not being able to do it. Democrats on Capitol Hill were skittish at the unprecedented numbers, the bill required moderate Republican votes to overcome a filibuster, and Rush Limbaugh—who for a while people were seriously calling the de facto head of the GOP—was busy railing against the “porkulous.” Perhaps $775 billion was the most that could ever have been done. That merely means that our government, collectively, couldn’t rise to the moment.

The undersized stimulus bill, however, was not nearly so damaging as the government’s hard turn toward austerity following the Tea Party wave in 2010. The new class of arch-conservative Republicans arrived in Washington demanding steep budget cuts and threatened to take the country’s debt ceiling hostage in order to achieve them. And they succeeded. The Manhattan Institute has calculated that Congress enacted $889 billion worth of spending cuts over the last six years of Obama’s term. Those, combined with tax hikes and the waning stimulus spending, acted as a powerful weight on the economy. According to the Hutchins Center’s Fiscal Impact Measure, federal budget policy was a net drag on GDP every quarter from 2011 through 2014.

Jordan Weissmann/Slate

It is impossible to know exactly how much of the GOP’s mania for budget cuts during the tea party era was the expression of sincere, small-government ideology, and how much of it was pure, partisan power politics aimed at kneecapping the administration. Given the party’s willingness to ignore deficits during the Bush and Trump administrations and in some cases embrace the very Keynsian ideas they once mocked—see: Mulvaney, Mick—it’s hard not to assume that much of it was the latter.

But bad-faith politicking isn’t the only thing that makes Washington’s mid-recovery turn to austerity so galling. It’s the way mainstream moderates and media figures abetted it by treating the national debt as an urgent crisis in the middle of what was effectively a depression. Paul Ryan was hailed a serious wonk for advocating vast tax and spending cuts. Based on the press coverage, you’d have thought the Bowles-Simpson deficit reduction committee was meeting to draft plans to divert an asteroid from smashing into earth. Obama himself tried and luckily failed to strike a “grand bargain” on debt reduction with House Speaker John Boehner. There was a consensus to treat debt as a clear and present danger even at the moment when the economy desperately needed the government to spend more.

The Obama administration’s weak response to the foreclosure crisis, which peaked during its first term, was yet another self-inflicted injury that slowed the recovery, by leaving the housing market to spiral downward and households to struggle with their debts. From 2009 through 2012, there were more than 9.4 million foreclosure filings in the U.S., according to ATTOM Data Solutions. In the face of this ever-expanding sinkhole, the White House erected a pair of cautious programs known as HAMP and HARP that were designed to let troubled borrowers lower their monthly mortgage payments, but were plagued by design and implementation flaws, and helped far fewer Americans than expected. Where the administration promised that HAMP would keep 4 million homeowners out of foreclosure, for instance, it only modified 1.1 million mortgages through 2012, and many beneficiaries later fell back behind on their payments anyway.

As a Senator and presidential candidate, Obama had publicly supported more dramatic efforts to rescue homeowners, specifically legislation that would have allowed so-called “cramdowns,” where judges could slash mortgage debt in bankruptcy court. But as president, he never put much muscle into the idea, despite backing from some moderates in Congress, or pursued any of the other bold options that experts and even Republicans had floated. So why did he settle for a more tentative approach?

Part of it was politics. The White House worried that it would face backlash for helping irresponsible homeowners—recall that the Tea Party started (in name, anyway) when CNBC’s Rick Sanetelli uncorked a rant from floor the Chicago Mercantile Exchange about how the government was baling out “losers” who couldn’t pay their mortgages. Part of it was difficulty: Designing a working housing program posed all sorts of technical challenges. And part of it was also a matter of priorities: Some of the administration’s top economic officials, particularly Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, believed that the only way to restore the economy to health was to fix the financial sector so it would lend, and saw helping homeowners out of their unpayable debts as secondary at best. According to one famous account, Geithner once suggested that the point of HAMP was to “foam the runway,” for banks, meaning to protect their balance sheets by slowing down foreclosures a bit. It implied he saw the housing rescue chiefly as a way to aid Citibank, rather than overextended families.

The Federal Reserve deserves a heaping portion of blame for our anemic recovery as well. After the fall of Lehman Brothers, the central bank took extraordinary measures to both save the global financial system and stimulate the U.S. economy, often bucking conservative critics who warned hysterically about hyperinflation and demanded more hard-money policies. But in the later years, it likely slowed the recovery by hiking interest rates prematurely, in a bid to make sure inflation stayed in check.

It did this despite the fact that inflation was more or less nowhere to be seen. The Fed aims for 2 percent annual inflation. Year after year, it missed that target. Yet policy makers still worried that rising prices were just around the corner. The reason was that economists have traditionally believed in a relationship between unemployment and inflation, known as the Philips curve, where as the former falls, the latter rises. As the jobless rate declined, the Fed’s models suggested that prices would finally go up. They wanted to get ahead of the curve, and prevent inflation from suddenly flaring up, by raising rates early, but slowly.

As economists Adam Ozimek and Michael Ferlez have documented, the Fed made a fundamental mistake: Over again, its members underestimated how far the unemployment rate could fall before inflation would become a serious concern. (It’s currently at 3.5 percent, a historic low). They weren’t alone: As early as 2014 and 2015, prominent mainstream economists were arguing that the U.S. had already reached full employment—effectively, that everyone who could conceivably get a job already had one. The press contributed, publishing stories about supposed shortages of construction workers and other skilled employees. They were all wrong. Today, Americans are still coming out of the woodwork looking for jobs, and the employment rate keeps rising.

How significant were the Fed’s errors? Its decision to increase rates in late 2015 likely contributed to what’s come to be known as the “mini-recession” of 2016, an industrial downturn that hit the Midwest, and may very well have boosted Donald Trump’s presidential run. It held off on hiking rates for another year, but even then, its increases probably came too fast, too early. Ozimek and Ferlez estimated that 1 million more Americans might have had jobs in 2018, had the Fed done a better job assessing the labor market.

The last ten years could have been worse for the United States. After all, there are parts of Europe that still have yet to heal entirely from the crisis. Meanwhile, the job market is humming. Middle class incomes are, believe it or not, at all-time highs. Growth looks pretty stable. Wages are rising. Compared to the cataclysmic recession that punctuated the Aughts, things are good. Even Donald Trump’s trade war—another needless self-own—didn’t plunge the economy into another downturn, in part because some people in power seem to have learned lessons from their past mistakes. The Federal Reserve may have averted another recession by cutting rates three times this year, and vowing to hold them down until it finally sees inflation actually rise above its target and stay there.

But this was decade was not a slow march to a happy ending. It was miscarriage of economic policymaking that left millions without work for far longer than they needed to be. If we remember that—and why it all happened—maybe we won’t have to go through it all again.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2ZwjsJh

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言