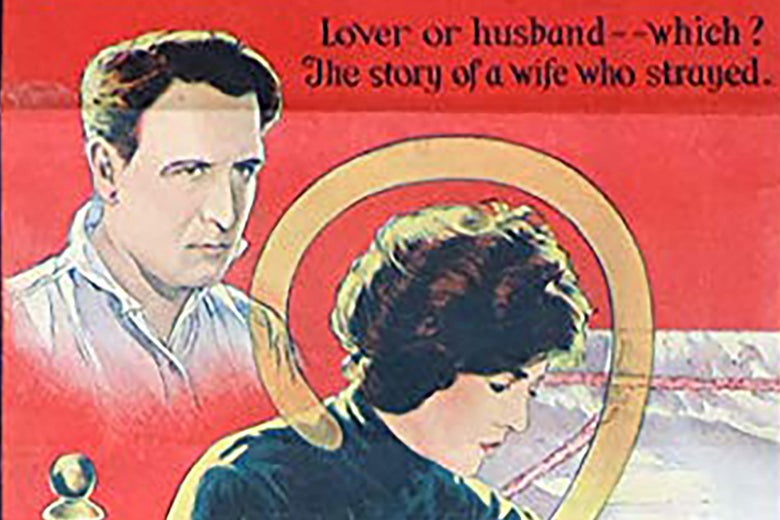

The poster for the 1924 film The Next Corner, which one critic called “about as poor a production as anyone would want to stay away from.”

Paramount

On Jan. 1 of this year, works of art first published in the United States in the year 1923 entered the public domain and became available to republish, remix or adapt at will. It was the first time that had happened since 1998, thanks to Congress’s perpetual extensions of the terms of copyright, so to help readers sort through what newly-public-domain art was worth reviving and what should be avoided at all costs, Slate published a guide to the worst art of 1923, according to the critics of 1923. On Wednesday, another year’s worth of movies, books, plays, and music will be ours to do whatever we want with. Duke Law School’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain has put together a list of some of this year’s highlights, and just like last year, there’s some wonderful work in the mix: Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr., E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, and George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue will soon belong to all of us.

But as usual, most of the art produced in 1924 was a disaster, and most of the critics knew it. Here is a selection of work from 1924 that critics in 1924 thought was perfectly dreadful, together with excerpts from their reviews. The biggest difference between the vicious pans of 1923 and 1924 is that several critics acknowledge that bad art can be enjoyable because it is bad, almost as though you can see critics and audiences alike developing the tools they will need to survive the twentieth century’s mass media in real time. If any of these books, movies, or plays seem like they’d still have camp value for a modern audience, you’ll be able to republish, remake, restage, or remix them in just a few short hours. We urge you to refrain.

Across the Street, by Richard A. Purdy

“Seeing Things at Night,” Heywood Broun, The Miami News-Metropolis, March 29, 1924.A new play called Across the Street has just come to Broadway and while it would be excessive to place it beside Survival of the Fittest, it is easily bad enough to hold an audience spellbound from beginning to end. Unless we are much mistaken the author has written it with full sincerity. These unconscious burlesques beat the premeditated article every time. Possibly there is something just a little cruel in enjoying bad work. It may well be that the spectator is amused by noting the gap between what the author is trying to do and what he has actually accomplished.

But, granting all the ethical objections which may be brought against my attitude I must confess that I had a fine time at Across the Street. … To see Across the Street is to long to be young again, a college freshman and just a wee bit stimulated. … Before the first act has ended everybody can perceive that here is an awful play and soon this very quality begins to work to its advantage. The shrill implausibility of all that happens is an asset. Every vice becomes a virtue.

Daughters of Today, directed by Rollin S. Sturgeon

“Lots of Joy for Filmgoers,” Helen Klumph, Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1924.…a strange and maudlin crazyquilt of flappers, sex, aged parents and booze parties, directed by Rollin Sturgeon, and called Daughters of Today, represented the lowest level of human endeavor in the movies. … It pains me to report that [it] is doing a big business.

Everywhere one goes the hostess greeting is apt to be, “Don’t take your wraps off. We’re going to take you to the funniest movie you ever saw.”

“They tell me there isn’t a single natural or life-like touch in Daughters of Today and everyone just shrieks at it. We’ll have to get there early or we can’t get in.”

Sometimes I wonder if movie makers aren’t fostering too much of this sentiment by continually putting out pictures that can only be taken as a joke.

The Gay Ones, by Charles Hanson Towne

“Recent Fiction,” Los Angeles Times, Aug. 10, 1924.…as a writer of fiction, [Towne] is beyond criticism. For the best that one can say of his work in this field is that it is pleasant trash. Flashy, overdrawn, sentimental and forced is The Gay Ones. Not the worst novel of the season, but the most irritating, in that behind all its glitter and falsity, one detects an author with a mind, doing his worst. Then, too, the very fact that Mr. Towne has the knack of holding the reader’s interest, adds to the irritation.

This is what the slip cover tells you about the book: “A novel of the Long Island smart and fast set, with a numerous cast of characters, each a type that all who have the most casual contact with this life will recognize. Under the surface of jazz, cocktail and champagne, ‘petting,’ and paint and bridge, the mismatched couples, the blasé young—Mr. Towne sees human beings still, with human traits they cannot paint out with all the glittering gilt of their lives or drown with highballs.”

You are not to suppose that Mr. Towne approves of all this. Quite the contrary. Hence, this may be looked at as a novel with a purpose; in fact, with two purposes. The first is to pile up royalties. The second is to be an awful warning against the gay life. May it succeed in both.

The Innocents, by Henry Kitchell Webster

“Father and Son Novel is Stupid, Reviewer Finds,” Bert Roller, The Tennessean, Nov. 23, 1924.The Innocents is a rather striking title for a very stupid book. I expected much more than Mr. Webster was able to give me, especially when I read the subtitle, “A Novel of Father and Son.”

But perhaps there isn’t much more to expect from adolescence literature. … In fact, we have grown to accept the monopoly of [Booth] Tarkington in this field. An American writer must keep entirely away from Tarkingtonesque mannerisms—or he suffers the indignity of being accused of copying. Mr. Webster succeeded in evading all such mannerisms. But his success has left him sterile. He has given us a purely mechanical book, glibly uninspired.

The Needle’s Eye, by Arthur Train

“The Reading Lamp,” J.B.C., South Bend Tribune, Oct. 12, 1924.The Needle’s Eye is probably the worst novel of the year; which is not to say that it will not be a big seller. Better things might have been expected of Arthur Train, whose “Tutt and Mr. Tutt” stories in the Saturday Evening Post have amusingly portrayed the triumph of virtue over vice in the minor courts of New York. But in this book, with the exception of a sketch toward the end about the last hours of a wealthy old reprobate, the organization of the story is poor, the writing indifferent and the dramatic values wretchedly botched. …

The author’s idea seems to be to show the troubles which accompany the ownership of great wealth, and to prove that even a millionaire cannot buck against economic forces. Union men will probably consider the book anti-labor propaganda. My quarrel with it is because it is a wretchedly executed work.

The Next Corner, directed by Sam Wood

“Talking Films as Crude as Movies Were 20 Years Ago,” Maurice Henle, The Evening Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), Feb. 23, 1924.The Paramount picture The Next Corner, despite its cast of Conway Tearle, Dorothy Mackaill, Lon Chaney, and others of equal note, is “about as poor a production as anyone would want to stay away from.” … a sure cure for insomnia. There is a rumor the name of The Next Corner will be changed, but a rose by any other name smells just as sweet. They should have left Kate Jordan’s novel sleeping between its covers.

Orphan Island, by Rose Macauley

“ ‘Orphan Island’ a Stupid Volume,” Hunter Stagg, Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 22, 1925.Just what happened to [Macauley] when she wrote Orphan Island it would be difficult to say, but as it is her first really stupid book, I suppose one shouldn’t be too hard on it. The trouble with the book is plain enough. All through it she seems to be tuning up her instruments for an orchestra of mirth—which never plays. Even your unmarred enjoyment of the first few chapters is a sort of anticipatory enjoyment of the delightful satiric comedy you think is being carefully prepared.

And after a while you begin to wonder what is holding it back. You think that it is going to begin on the next page, and it is a tribute to Miss Macauley that you keep thinking that through as much as half of the book. But the feeling of pleasurable expectancy is never gratified.

The Right to Dream, by Irving Kaye Davis

“Broadway,” by Brett Page, Muncie Sunday Star, June 22, 1924.The Right to Dream is about as untruthful as some lemon merengue pies. The froth, you know, looks diaphanously solid, but is as solid as sweetened water. Mix prussic acid with the meringue and you will have the idea of The Right to Dream.

A young man and a young woman love and are married. He is a genius, so we are assured time after time, though no evidences of the alleged fact are offered. He chats in squalor with his wife. He cannot sell his play, though it is the greatest ever written. There are two acts of this. In the third act, Mr. Alleged Genius accepts a job as editor of a magazine. He is forced to this terrible deed to save his wife from starvation. But so obsessed is he by working as an editor—think of prostituting his genius to so terrible a degree!—that just before the final curtain he blows his alleged brains out. …

The Right to Dream may or may not be the worst play of its type we have ever seen. There may be others, but we have our doubts.

Sandra, directed by Arthur H. Sawyer

“At the Movie Theaters This Week,” T.M.C., Baltimore Sun, Dec. 16, 1924.When old man gloom drops in to check off his list of the season’s 10 worst movie plays the present reviewer hopes to be on hand to suggest Sandra for first place. … Of all the unmitigated twaddle masquerading under the guise of silent drama, Sandra is about the most unmitigated. By the time the first half of the film had been unfolded yesterday the spectators were beginning to titter gently. At the grand finale some of the more frank folk laughed out loud.

But obviously it was not intended as a comedy nor as a cross-word puzzle, though it might take the place of either. When the spectator is busied in piecing together the scenario he gets several magnificent opportunities for—let us say—a chuckle.

That’s it until next year, when we’ll all be able to publish sequels to The Great Gatsby without asking anyone for permission. Mine is called Trimalchio’s Revenge, and if you think the critics of 1924 could be harsh, just wait till I send out the advance proofs.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2ZCPJya

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言