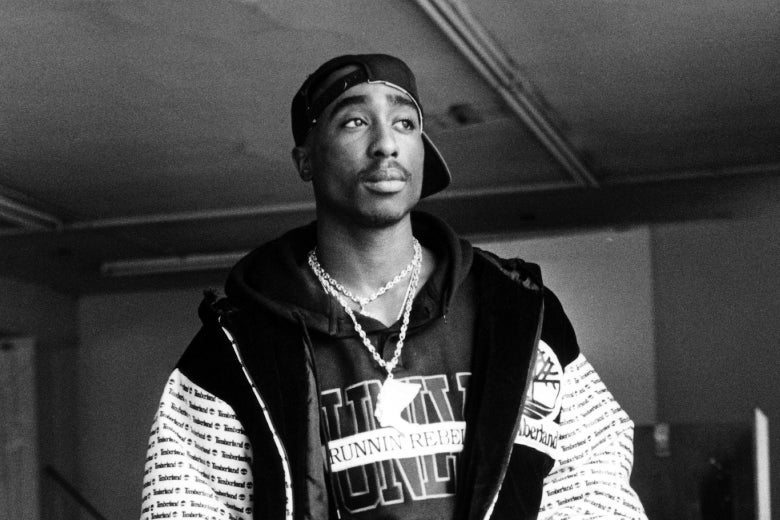

Tupac Shakur in Oakland, California, in January 1992.

Gary Reyes/Oakland Tribune Staff Archives/MediaNews Group/Bay Area News via Getty Images

On June 23, 1996, four LAPD officers went to the headquarters of Death Row Records to “verbally admonish” the record label. The officers had issued that warning at the behest of Death Row’s neighbors in the suburban enclave of Tarzana, California. There had been complaints about armed gang members coming and going and increasing reports of assaults, auto thefts, and robberies.

This might have been a particularly observant neighborhood watch, or it could have been a case of racial profiling. But it was true that Death Row had become a hangout for gangsters—and not just the Bloods that label head Suge Knight rolled with.

“There’d be Crips on one side of the couches and Bloods on the other side because Snoop [Dogg] was Crip affiliated at that point,” said Leigh Savidge, co-director of the documentary Welcome to Death Row.

Tupac Shakur publicly embraced that gangster ethos when he signed with Death Row. He got the letters “MOB” tattooed on his right triceps. He said it meant “Money, Organization, and Business.” But some people took it to refer to the Mob Piru, a faction of Bloods from Compton. Others said it stood for “Member Of the Bloods.”

Tupac had become the biggest star in hip-hop, but by 1996, Death Row was starting to fall apart.

Snoop went on trial for murder, in a case stemming from an altercation near his house three years earlier. After he was acquitted that February, he started to distance himself from the gangsta life.

A month later, Dr. Dre announced he was leaving Death Row. He’d grown weary of the violence surrounding Suge, and he wasn’t eager to work with some of the label’s newer artists, including Tupac.

Tupac came to feel the same about Dre. He was bothered that Dre never showed up at Snoop’s trial, and he thought Dre didn’t do enough to support Death Row in its beef with Bad Boy Records.

“[Tupac] was the one that pointed things out to us,” said Reggie Wright, Death Row’s head of security. “He was the one that was like, ‘This a disloyal motherfucker. I don’t want to be around him. I ain’t feeling him.’”

It seemed like Tupac and Death Row were going to ride together, everyone else be damned. That’s how it looked from the outside, at least. But even as Tupac was calling out Dre for disloyalty, he was making his own moves away from Death Row.

In 1996, Tupac formed his own production company, Euphanasia. He was making plans to start a label under his new stage name, Makaveli. He also spent much of that spring and summer filming two movies, Gridlock’d and Gang Related. He told people in the film business that he wanted to start working on different kinds of projects: a Western starring young black actors and a movie about the uprising led by enslaved preacher Nat Turner.

“I think he knew Death Row was going to be a roadblock for him,” said Allison Samuels, who covered hip-hop for Newsweek.

The surest sign that Tupac was considering a different direction came on Aug. 27, 1996. That’s when he fired Death Row lawyer David Kenner, a former defense attorney who’d made his name representing drug traffickers. He came to power at Death Row by attaching himself to Suge Knight. Kenner got Suge and Death Row’s artists out of a bunch of legal jams, and he came to play a big role in the label’s day-to-day operations.

It was Kenner who had engineered Tupac’s release from prison. But first, Tupac had signed a contract with Death Row—an agreement that also made Kenner his legal representative. Once he was on the outside, Tupac grew frustrated with that arrangement.

The final straw came when Kenner denied Tupac access to some music he’d been working on in the studio. That’s when Tupac fired him—a move that some friends and outside observers considered rash. To cut ties with Kenner was a very big deal.

George Pryce, Death Row’s publicist, says he came to believe that Tupac’s loyalty only went so far.

“Tupac wanted to start his own company, and that’s why he was doing what he was doing with Death Row to make that money that he needed,” Pryce said. “Tupac was using Death Row as a means to an end.”

It often seemed like Tupac couldn’t think more than one second ahead, but he also appeared to understand, on some level, that he couldn’t keep acting this way forever. He had to make a decision—about what kind of career he wanted to have and what kind of life he wanted to live.

In the summer of 1996, he was increasingly essential to the survival of Death Row Records, and increasingly ready to strike out on his own. He was on the verge of making a choice.

And then he went to Las Vegas.

What happened in Tupac Shakur’s final hours? How close was he to quitting the gangsta rap life? And how would one last reckless act come to define his legacy?

This excerpt has been edited for condensed and edited for clarity. Subscribe to Slow Burn Season 3: Tupac and Biggie now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. And to hear the interviews we just couldn’t fit into the main episodes, join Slate Plus.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2Rgkhn8

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言