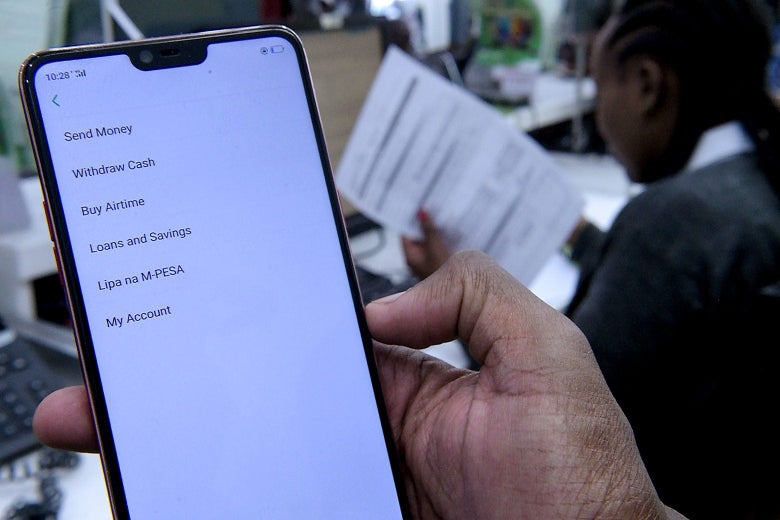

A Safaricom employee displays the M-Pesa money transfer service on a smartphone inside a mobile phone care center in Nairobi, Kenya, on Nov. 22, 2018.

Simon Maina/AFP via Getty Images

The future is looking dim for Libra, Facebook’s attempt to build a global cryptocurrency. This month, European finance ministers agreed to block Libra within the EU until they develop a shared way to regulate it. In the U.S., Libra has faced bruising skepticism from U.S. officials as ideologically diverse as President Donald Trump, Reps. Maxine Waters and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell—a bad portent for a project that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg says won’t happen, in any country, without U.S. regulators’ rubber stamp.

It’s easy to see why Libra seems at best useless and at worst dangerous to Americans and Europeans. We get to have bank accounts denominated in dollars and euros, remarkably stable currencies with low rates of inflation, meaning our savings don’t get eaten away overnight. As obnoxious as our banks may be, we generally can trust that they will not run away with the money we deposit. The U.S. payments system is a little slow compared with some countries including Mexico, Poland, and South Africa, but it basically meets our needs. In this context, the prospect of being able to buy stuff from Instagram influencers more easily, in exchange for Facebook having even more data to potentially misuse, does not sound compelling.

But the 1.7 billion users of Facebook’s platforms outside the U.S. and Europe actually could use something like Libra to store and transfer money. These users would take on most of the risk and harm if things go wrong with Libra. And if everything went right—it’s a big if—they’d gain the most too. It’s why, even if Libra is dead in the water, I hope the idea behind it isn’t.

Facebook announced Libra back in June, although the proposed digital currency and payments system is officially being led by a nonprofit with voting members including Facebook, 17 other companies, and four nonprofits. A “stablecoin,” Libra would be backed by reserves of hard currency including the dollar, euro, and Japanese yen, so its value wouldn’t fluctuate as wildly as that of bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. A new Facebook subsidiary, Calibra, is developing a wallet that would let people send Libra through a stand-alone Calibra app or via other services like Facebook-owned WhatsApp. Libra would move across a blockchain, unlike most international money transfers, which primarily go through a system called SWIFT, and this, presumably, would make Libra transfers cheaper, faster, and more accessible, especially if people are able to transfer Libra on any kind of cellphone, as the Libra coalition anticipates will happen once other parties develop digital wallets.

The 1.7 billion users of Facebook’s platforms outside the U.S. and Europe actually could use something like Libra to store and transfer money.

With or without Facebook’s involvement, such a system could mean a lot to someone who lacks a safe place to store money. Consider the case of M-Pesa in Kenya.

M-Pesa is a mobile money service offered by Safaricom, a Vodafone affiliate. It’s not a cryptocurrency but a service that lets you store, send, or receive Kenyan shillings (or a handful of other fiat currencies). Within two years of M-Pesa’s launch in 2007, more than 65 percent of Kenyans had received money via the service. M-Pesa effectively allows anyone in Kenya with a cellphone—smart or not—to send or receive or store money on their devices, a boon to those without bank accounts. Around the world, bank accounts are rarely offered for free to people who can’t make large deposits. But transferring your M-Pesa into hard currency was relatively easy and cheap; Safaricom paid kiosks around the country a small fee to exchange M-Pesa back and forth into cash. As M-Pesa grew in popularity, users had to convert it back to cash less frequently; grocery stores, utility providers, and doctor’s offices began accepting the mobile money as a form of payment. Economists Tavneet Suri and William Jack estimated in the journal Science that M-Pesa lifted 194,000 Kenyans out of extreme poverty, in large part by making it much easier for Kenyans to accumulate savings. If a stablecoin coupled with an easy-to-use wallet could replicate some of the benefits that M-Pesa users have in Kenya, it could make a small but important dent in global poverty.

It’s not just the ability to hold money that matters; it’s also the ability to move money cheaply. Joe Huston, the chief financial officer of GiveDirectly, an organization that sends cash assistance to people living in extreme poverty around the world, told me that in countries like Kenya with well-functioning mobile money systems, it costs GiveDirectly about 1.5 percent of the total cash transfer to send money to poor families, which includes both what GiveDirectly pays to send the assistance and what the recipients pay to turn their mobile money into cash. In other countries with more limited mobile money ecosystems, like Malawi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Bahamas, GiveDirectly’s costs are roughly twice as high. (GiveDirectly is not affiliated with the Libra Association.)

In theory, Libra would bring down or eliminate the cost of these transfers because, like Bitcoin, Libra would bypass the expensive international bank transfer systems. This does rest on some big assumptions: that people around the world will be happy to hold onto Libra, and that third-party operators will spring up to let customers convert Libra to local currency at an affordable price. Dante Disparte, the vice chair of the Libra Coalition, told me he believes a network of local third parties will eventually arise to accept and exchange Libra. In that sense, the most important partners for Libra won’t be multinational corporations but individuals like the street vendors who now accept M-Pesa.

There’s a compelling reason to reduce these transfer costs: remittances. According to the World Bank, in 2019, low- and middle-income countries are expected to receive $550 billion in remittances, more than three times what they receive in foreign aid. In Haiti, Honduras, and South Sudan, remittances account for more than 20 percent of GDP. “A lot of the existing rails [to send remittances] can take between 5 and 10 percent [of the value] between the person sending it and the person receiving it,” Huston said, adding that “getting those fees down would be hugely beneficial to people in poverty.”

Again, this definitely isn’t simple. In making money easier to transfer, Libra will have to find an inexpensive method for fighting money laundering that meets the requirements of U.S. and other governments. The coalition will have to find markets that aren’t already saturated with existing, well-functioning payment and money storage products, and they’ll have to keep local governments happy. Generally speaking, in the countries where moving money is especially difficult and expensive, it’s because governments have adopted protectionist policies.

The biggest case for why this should all be done by an organization tied to Facebook—as well as an important argument against it—is scale: If you’re going to succeed in launching a widely used global currency and payment system, it helps to be a massive company with deep pockets and more than 2 billion existing active users.

Fighting money laundering is one of the places where you’d expect the Libra Association to have a head start over other players. A lot of companies, both “fintechs” and big banks, have tried and failed to lower the cost of remittances. According to Connel Fullenkamp, professor of economics at Duke University, who studies remittances and financial market regulation, one of the obstacles remittances startups run into is the cost of verifying the identities of the sender and the recipient of the cash, something they have to do to comply with anti–money laundering laws, especially if they’re headquartered in the U.S. Libra says it plans to verify user accounts by asking users to upload photos of their government-issued IDs, the type of technological solution made easier by Facebook’s expertise in facial recognition. And depending on how regulators proceed, Facebook has another head start here as well: Governments might decide that validating consumers’ identities by referencing their Facebook profiles is about as reliable at preventing money laundering or terrorist financing as existing methods banks are allowed to use, like checking credit bureau data. If that sounds dystopian to you, don’t forget that credit bureaus are ethical dumpster fires in their own ways too.

And if Libra takes off in the developing world as a safe place to accrue savings and an easy way to move money, regulators will have to reckon with the very mixed economic consequences of their citizens choosing a cryptocurrency over the local currency. If a lot of people in a particular country decide they want to hold their savings in Libra, it could weaken the local currency. Access to foreign currency tends to create “a system of haves and have-nots,” says Fullenkamp. When countries see a massive outflow from their own currency to a foreign currency, the government “loses control over the value of their own currency”; as fewer people use the local tender, it becomes even less stable. Countries like Ecuador and El Salvador have gone so far as to ditch their local currencies altogether, giving in to their citizens’ preference for stable U.S. dollars over volatile and rapidly inflating sucres and colones. Their citizens gained the ability to go to a grocery store and know today’s prices would be roughly the same as yesterday’s, but their central banks lost the ability to weaken the currency to encourage exports or to strengthen the currency to make imports cheaper.

Libra’s sweet spot would likely be countries that receive a high volume of remittances and have governments with liberal currency policies, but where the existing mobile money environment is fragmented or limited.

Some developing countries, fearing that loss of power, try to limit their citizens’ access to foreign currencies altogether. Although Libra’s Disparte specifically mentioned Ethiopia as a remittance corridor that could benefit from Libra (in 2017, Ethiopia received $277 million in remittances from people living in the United States), Teddy Tassew, a fintech consultant based in Addis Ababa, pointed out that Ethiopia’s government has a particularly strict position on currency issues. “The country doesn’t allow moving money out of Ethiopia as an individual due to strict monetary policy on the foreign exchange, so you would have to use informal ways to move money out—some illegal,” Tassew said. He added that citizens who receive remittances are “expected to convert their foreign currency into birr right away.” While he said he was somewhat “optimistic” that Libra could help lower the cost of international remittances, he also acknowledged it would be a “big hurdle” for Libra to convince central banks in Africa to permit them; that same challenge is no less important in most of the developing world.

Although Disparte flagged that the Libra coalition has spoken to roughly 40 regulatory agencies or central banks, many in the developing world, some of which he said were supportive of the project, he declined to cite specific examples, explaining that the “regulators themselves really like professional discretion.”

Fullenkamp expects that even if some countries blocked Libra, at least some developing countries would be open to it, particularly those whose economies are particularly dependent on remittances. Beyond the countries like El Salvador and Ecuador that have already “dollarized,” others, like Lebanon, where remittances are the source of roughly 20 percent of GDP, let their citizens freely hold checking accounts in foreign currencies. Ecuadorian, Salvadoran, and Lebanese regulators might object to Libra for some of the same reasons as Western regulators, but they’re not entirely opposed to the general idea of their citizens favoring nonsovereign currencies. Libra’s sweet spot would likely be countries that receive a high volume of remittances and have governments with liberal currency policies, but where the existing mobile money environment is fragmented or limited.

Is Facebook far too troubled to spearhead the initiative? And if the social network didn’t do it, who could? Fullenkamp points out that most successful consumer payments systems are launched either by telecom providers (like M-Pesa, launched by Vodafone) or by tech companies that already have a large preexisting customer base (like Alipay and WeChat Pay, launched by Alibaba and WeChat). Generally speaking, it’s much easier to gain traction with a payments system if a bunch of people already have your app installed. But telecom-based solutions are inherently going to be globally fragmented. There’s not much overlap, for example, between the telecom companies in the United States and those in sub-Saharan Africa. Notably, Vodafone has signed the Libra coalition’s interim articles of association, a hint that the company doesn’t expect to solve the global payments problem on its own. A Vodafone spokesperson said that while no firm decisions had yet been made, M-Pesa accounts may one day accept Libra alongside the Kenyan shilling and other currencies.

There are plenty of legitimate reasons that Facebook and Libra could succeed where others have failed to bring down the costs of sending money worldwide and to make it easier for anyone with a phone to have a cheap and fairly safe place to store money. Arguably the only other company that would be comparably well positioned to launch a global payments system is Google—nobody else has so many digital users across both the developed and the developing worlds—and to tech critics, Google is nearly as scary as Facebook.

Is it terrifying to imagine Facebook running a global currency, even if it’s only the most important partner in a nonprofit coalition? Sure, a million things could go wrong. What happens if the next financial crisis is caused by a bunch of Libra banks doing risky Libra loans, and all the borrowers default, leaving the banks without enough Libra to make their middle-class Libra depositors whole? And what if, despite the Libra coalition’s vague pro-privacy affirmations, Libra data is used to extend the reach of Facebook’s surveillance?

But Western regulators also need to fully grapple with the radical potential of an efficient global payment system. It’s easy to take for granted having a safe, relatively cheap way to store and move your money, and yet without those things, it’s nearly impossible to build any measure of financial stability. Facebook doesn’t yet have adequate answers for how to manage all the risks that Libra would create, but if the U.S. cares at all about global poverty, it should help Facebook figure out good answers—or put the money and time into building an alternative with the rest of the world.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2EJ6o9P

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言