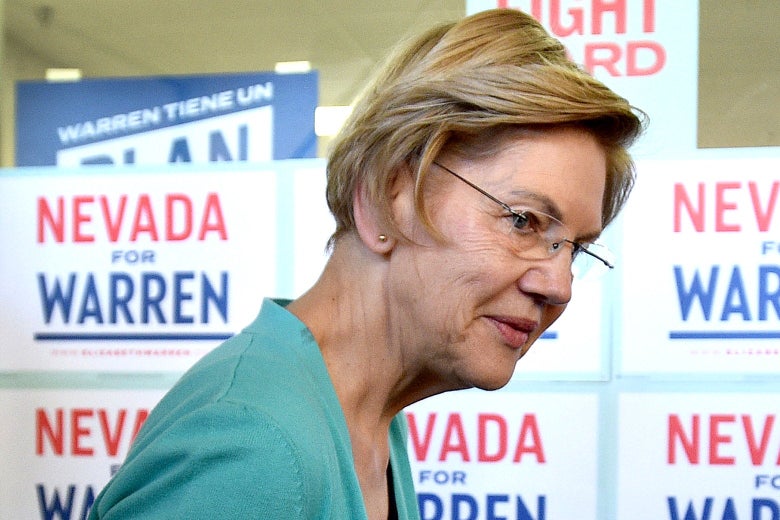

Elizabeth Warren in Las Vegas on Saturday.

David Becker/Getty Images

As Elizabeth Warren addressed a crowd of about 500 supporters in Las Vegas on Friday at the Clark County Government Center Amphitheater—one day before the Nevada caucuses in which she would finish in a distant fourth place—the Massachusetts senator wound into a familiar part of her stump speech. Describing how “I have known what I wanted to be since second grade,” a public school teacher, Warren told the story of how she married young, dropped out of school, returned to a $50-a-semester commuter college, got her degree, and was ultimately able to achieve her goal.

“I could pay for it on a part-time waitressing job,” she said. “I finished my four-year diploma and I became a special education teacher.”

Then came a line that she gives at every speech: “I’ve lived my dream job,” Warren said.

The point is that the younger Warren already struggled to reach her ambitions, priorities, and goals, and whether or not she wins the most powerful job on the planet, she has overcome long odds.

In Friday’s telling, though, that subtext carried particular resonance. Warren’s emphasis on the past-tense “lived” reflected a truth that has emerged in recent days and became much clearer after the votes were counted in Nevada: Sen. Elizabeth Warren is very likely not going to be the Democratic nominee for president of the United States.

Campaign surrogates argue against this, saying that a strong debate performance this past Wednesday in Las Vegas gave her campaign new life, showcased her skills at taking down arrogant plutocrats like Mike Bloomberg and Donald Trump, and resulted in a huge fundraising haul the night of the debate and a polling bounce. They note that there are still plenty of states left to be counted.

But the reality is that Bernie Sanders is opening up a sizable polling lead nationally and in many key states, and is building a steady delegate lead, which could soon become insurmountable. Even in her best new national poll, Warren trails Sanders by nine points in second place. In state poll after state poll released in the past week, meanwhile, she has often done no better than third. She is in fifth in a recent polling in South Carolina, where former Vice President Joe Biden still leads with Sanders in a close second. According to her strongest entrance polling showings in Nevada, meanwhile, Warren finished a distant third among black voters and fourth among Latino voters, trends that—if they continue—will only produce more drastic delegate deficits as the diverse Democratic electorate begins to have its say outside of the lily-white states of New Hampshire and Iowa.

Warren’s path to overtaking Sanders or even finishing in second in the delegate count is shrinking to virtually nothing—FiveThirtyEight’s latest campaign forecast puts her odds of winning the nomination outright at less than 1 percent and of achieving a plurality of delegates at 2 percent. By Super Tuesday next week, they will likely fall much closer to zero.

How did Warren, who as recently as November appeared poised to take the first two states and finish a strong second in Nevada, see her campaign collapse so completely? In talking with her surrogates, supporters, and would-be supporters in the waning days of the Nevada campaign, a theme emerged. While Sanders earned unshakable support among a hardcore following of die-hards and Biden did well enough among the more typical Democratic constituency and interest groups to survive Nevada with a chance to claim victory in South Carolina, Warren’s base of mostly college-educated liberals just could not make up their minds.

“I am seeking clarity,” Megan Creider said before Warren took the stage at the Clark County Government Center Amphitheater for the pre-caucus event on Friday. “I’m more of a Bernie supporter, but they do agree on a lot of the same issues, so I’m not against Warren whatsoever. I’m seeking some clarity from her.”

Creider was the first of nine people with whom I spoke—nearly in succession—at Friday’s event who told me that they were undecided or had already cast a ballot for someone else in early voting. Her uncertainty was typical, if not her support for Sanders.

“Right now, it’s between Warren and maybe [Pete] Buttigieg,” said Royce Ray, a former 23-year service member who said that getting Trump out of office was his top priority because he feared a disastrous foreign conflict might be undertaken by the impetuous president. “I think the top four are all good.”

Gustav Lukban and Carmelita Lukban, who sat in the back of the five-sixths empty outdoor amphitheater, both had already caucused early. They had voted for Buttigieg, with Warren as their second choice. “It was pretty close,” Gustav said. “I kind of second-guessed myself after I went with Pete. I was thinking, ‘Warren really was my first choice,’ but at the last minute I switched.”

“If he doesn’t reach that threshold, I’ll be rooting for Elizabeth,” he added.

Tracy Williams, who has a Ph.D. in educational leadership and is from Washington state, was also sitting near the back of the amphitheater. She had come in from Walla Walla to help knock on doors and get out the vote—not for Warren, but for Joe Biden. Williams had done this canvassing at the behest of a close friend and was unsure whom she would vote for on March 10, one week after Super Tuesday.

“I’m probably Warren, Biden, Klobuchar, and they could be interchangeable at any time,” she said. Williams, who had initially supported former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro before he dropped out and backed Warren, was there in part to see Castro, who was introducing the former Harvard Law professor. “When I read her education plan, I’m like, ‘Holy cow, I couldn’t have written a better one if I called all my friends in education and said let’s write this thing,’ ” Williams said. “I started reading the other plans and I’m like: ‘This woman has tapped into geniuses to put this stuff together, she didn’t just throw out some good ideas, she got the best of the best.’ ”

Still, Williams hasn’t been able to settle on a candidate since Castro dropped out. “Now I’m Warren, Biden, Klobuchar,” she repeated. “It’s a teeter-totter.”

Waiting in the selfie line after Warren made her case, UNLV student and Hawaii voter Cody Pinzon also said he was still undecided.

“Seeing a candidate in person is different than seeing a candidate online,” he said of why he wanted to attend. “I was leaning towards her. I might be leaning more towards Warren.”

At the Sanders event—just 10 minutes up the road at the Springs Preserve Amphitheater—there was little such ambiguity over who attendees were supporting, as 2,000 Sanders fans packed into the 1,500-seat outdoor venue, many of them decked out in Bernie gear. Jack Wagner and Chelsea Tadros, who left the event early, had come from Los Angeles to canvass—not for another candidate, but for Sanders. Wagner, who attended both the Warren and the Sanders events, said he was a bit taken aback by the subdued Warren crowd relative to the raucous Sanders supporters.

“It’s just like a stark difference in terms of vibes,” Wagner told me. “To be fair, it was a lawn, [but] going from the Warren one, where people were sitting down and it was kind of spread out and not as many people, and then this is just a lot of people and everybody’s standing up and screaming. Just, the energy’s very different.

“She did great,” he added of Warren’s speech. “I think she’s super charismatic, and I like her as a candidate, and I enjoyed watching her speak.”

Unlike the very progressive Wagner and Tadros, Warren’s supporters and would-be supporters were a mix of some who leaned more toward the progressive wing of the party and others who leaned more toward the moderate wing. That was one of the candidate’s biggest problems. Warren has tried in recent days to bill herself as the candidate who was best positioned to unite the two wings of the party. But that difference-splitting only served to send progressives to Sanders and to scatter the undecided moderates. According to the Washington Post’s entrance poll, Warren finished with just 16 percent of very liberal voters, second to Sanders’ 52 percent, and 7 percent of moderate or conservative voters, fifth behind Sanders, Biden, Buttigieg, and Klobuchar. In attempting and failing to appeal to these moderate voters by tempering her “Medicare for All” stance, Warren turned off any chance of winning over progressive voters while failing to turn around the center.

When I asked Wagner and Tadros what they would do if Warren was the nominee instead of Sanders, Wagner said that he would reluctantly “bite the bullet” and vote for the Massachusetts senator. Tadros interrupted, saying, “I don’t know, man.

“I like her, and she is charismatic, and I understand where her followers are coming from,” Tadros told me. “But she still believes in the capitalistic system to get the job done, and I don’t agree with that. I think that Bernie’s the best guy for the job right now.”

“It’s always hard, especially for working people that can’t take the time off for work,” said Julieta Garibay, a co-founder of the immigrant rights group United We Dream and a Warren surrogate, attempting to explain away the differences in rally attendance at the two pre-caucus events. “I’ve been door knocking in my state, Texas, and many of our communities have to have two jobs so going to a rally on a weekday can be hard, even if it’s a Friday night.”

Garibay was speaking with me at the Bellagio Hotel and Casino caucus site as dozens of hotel and casino employees piled into a Bellagio ballroom to cast their ballots. Many of these workers wore their work uniforms, and many wore “Unidos Con Bernie” stickers, despite the advice of their culinary union that Sanders’ health care plan would end their union medical coverage.

In the end, 76 of the 123 working, mainly Hispanic community members who showed up to caucus went for Sanders. In the initial round of results, just six caucused for Warren, and she failed to meet the 15 percent threshold. Her supporters dispersed in the final tally to the Biden count and to “uncommitted.”

When I asked Garibay before the caucus what results the campaign was hoping to see in Nevada, she had demurred. “We know likely that results won’t be until maybe Sunday if we’re lucky,” she told me. By Saturday at 4:30 p.m. local time, a few hours after caucusing ended at the Bellagio, NBC had called the race for Sanders. By Sunday evening, with 88 percent of the vote counted, Sanders had 47.1 percent of the awarded county convention delegates and outlets were able to make a call on second and third place, which went to Biden and Buttigieg with 21 percent and 13.7 percent respectively. Warren was in fourth with less than 10 percent, not enough to claim any delegates from Nevada.

Sanders was aided in his Nevada victory by a major advertising blitz, paid for by millions of dollars he’s taken in from small donors, and by an army of volunteers who knocked on more than 500,000 doors in the state. Biden’s strong but distant second-place finish was brought about by the sort of special interest and constituent-building—labor endorsements and support in minority communities—that has been more typical of Democratic Party politics for years, and which Warren has not been as successful at achieving.

At Biden’s pre–caucus day precinct captain training event, held at the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, some of the locals of the top unions in the country gathered to hear Biden speak. While nobody won the endorsement of the state’s powerful culinary union—whose voters Warren aggressively courted, appearing at a picket line on Wednesday and a women’s event on Tuesday—Biden has had the backing of the International Association of Firefighters, the Amalgamated Transit Union, and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

In explaining his support for Biden, Ray LeClair—a member of the firefighter local—cited specific legislation Biden helped pass during his time in the Senate that provided benefits to surviving family members of firefighters who die in the line of duty and overtime for public sector workers.

When LeClair, who was caucusing for the first time, was asked if he had a backup to Biden in case the vice president didn’t reach the threshold for viability at his caucusing site, he was adamant that his support would be going to Biden. “That’s really not what we’re here for, right?” he told me. “We’re here to make sure that the vice president meets that threshold and then bring the people that don’t make that threshold over to Joe’s side.”

Bret Tantlinger, an IBEW member, said he was skeptical of some of the other candidates because he didn’t feel their health care plans were realistic. He also believed that Sanders, who has listed himself as an independent in the Senate for years, is “riding the coattails of the Democratic Party.”

While the bulk of culinary union employees appeared not to have felt the same way as Tantlinger, the support of his union and others like them helped Biden claim second place in Nevada. According to NBC’s exit polling, Sanders took 34 percent of the union vote, but Biden finished with 19 percent for a strong second. Warren had 11 percent of the union vote.

Similarly, Biden had a strong showing among black voters in the first diverse state of the primary season. Both the Biden and Warren campaigns had done outreach in the black community in Las Vegas, but Biden’s efforts were clearly more effective. The day before the primary, Jill Biden made an appearance on the state’s only black public radio station, KCEP, and the Bidens received effusive praise from the program’s hosts.

“He showed us that KCEP was important,” one host said of the family’s attention to the station.

“He keeps his promises,” Jill Biden said.

“And that he kept his promise!” the host repeated.

Jill Biden was meant to appear at a community center of black senior citizens following her radio appearance to talk up the Biden campaign but backed out. A Nevada Biden campaign staffer told me the cancellation was because a local carpenters union was picketing one of the building management firms in the complex that housed the senior center over a payment dispute.

Despite the cancellation, the event still seemed to have its effect. The visit was to double as a celebration for all of the February birthdays for community members and the center was plastered in wall-to-wall Biden signs, as seniors clad in Biden stickers danced to 1970s funk music and sat around chatting.

“I have good confidence that he’s going to do what he says he’s going to do,” Atlee Macklemore told me of why she supported Biden. “He worked with the president.”

“He can get Trump out of there,” Evelyn Johnson said.

“I like all of them, I just want somebody to beat Donald Trump,” Jacquelyn Washington said. She also supported Biden.

The day prior, Rep. Joaquin Castro had turned up at the same center as a surrogate for the Warren campaign, though he didn’t sound too confident that many of the seniors would be backing her. “I do think that in places that are in the first few states, whether it’s Iowa, New Hampshire, or Nevada, they see a lot of politicians,” Castro told me of his reception. “But I felt like people were engaged in terms of planning to go out and vote.”

In the NBC Nevada entry poll, Biden led among black voters with 36 percent to Sanders’ 25 percent. Warren finished tied for third with 13 percent. In South Carolina, the site of the next primary on Saturday and Warren’s last chance to earn a campaign showing stronger than third place before Super Tuesday, more than half the electorate is made up of black voters.

On Sunday, I attended a Warren get-out-the-vote rally in East Los Angeles where a little more than 50 attendees came out to see Julián Castro speak.

Despite the disappointing finish in Nevada, the former HUD secretary sounded bullish notes on Warren’s chances of building on her campaign momentum from a debate in which it was widely accepted that she had eaten Bloomberg’s caviar.

“The fact is that less than 5 percent of the delegates have actually been allocated already,” Castro told me. “This race is just beginning. In places like California, what I’ve seen is that she has tremendous enthusiasm.” Castro cited a Long Beach canvassing event he went to earlier in the day where 75 volunteers had turned up.

“She continues to gain support among Latinos, and I think that’s going to pay off in California and Texas,” Castro told me.

On Sunday evening, Sanders held an event in Austin, Texas, with nearly 13,000 attendees.

In Nevada at least, Hispanic voters did not turn out for Warren. According to NBC’s entry polling, Sanders won that demographic with 51 percent support, Biden finished second with 13 percent, and Warren finished fifth with 9 percent, behind Buttigieg and Tom Steyer.

“I mean, he did well, but he only has 1.7 percent of the delegates that are going to be allocated, so we still have states with a huge Latino population in California and Texas and Florida and they’re not all the same either,” Castro said. “I’m confident that Sen. Warren also has a good support base in the Latino community, and that will show itself in the states to come.”

“[Bernie’s] got a very progressive message so he’s getting all the Latinx [voters] because we’re more progressive,” said Roberto Murillo, a 68-year-old medical social worker with a master’s degree in anthropology, who was at the L.A. event to see Castro speak. “People of color are more progressive. They like the ideas of Medicare for All. The push for squashing student debt. All of the things that he’s really been advocating since day one, especially the Medicare for All.”

Murillo said he supported Warren because he was skeptical that Sanders could actually get those policies done. “It may resonate with somebody, but what is the reality, what is the pragmatism,” he told me.

Murillo and four family members had voted early for Warren, but if Sanders is the eventual nominee, he will support him, and he sees other possibilities as well.

“I’m going to support the Democratic candidate,” he said, “whether it be Sanders or Buttigieg, who’s running for me as a strong second.”

Slate is covering the election issues that matter to you. Support our work with a Slate Plus membership. You’ll also get a suite of great benefits.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2w0DTmK

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言