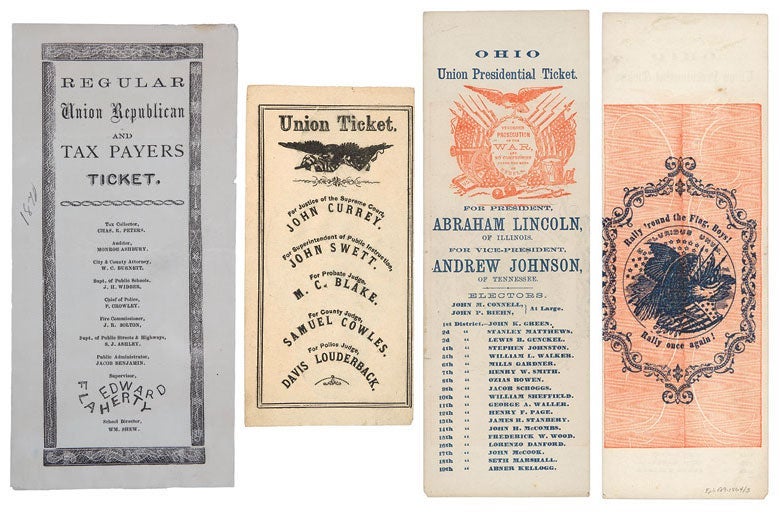

Left to right: a Prohibition ticket from Boston, 1873; a Union Republican ticket from California, 1868; a Union Ticket from California, 1867.

American Antiquarian Society and California Historical Society

Long lines, bureaucratic disorganization, confusing ballots, and machine malfunctions—our system of voting has never seemed more complicated and precarious. But it used to be far, far worse.

We should appreciate the non-event of Election Day: For a long time, it wasn’t that way. Election days were frequently raucous, violent affairs. Local taverns were often used both for campaigning and as polling locations, with party workers sometimes persuading the undecided with cash or whiskey. Newly arrived immigrants were often naturalized en masse and bribed with basic necessities in exchange for their vote; citizens were subject to overt intimidation from their neighbors, their employers, and the party bosses. Until electoral reforms overhauled the system in the late 1880s, casting your ballot was very much a public act: Everyone knew how you voted.

In the early days of the republic, the “ballot” was often nothing more than your voice. Citizens verbally announced their preference to a clerk who registered them in a poll book—hardly an ideal system for those worried about social repercussions. While these simple systems endured (much like the caucus system continues today in Iowa) they weren’t as useful when things scaled up. Paper ballots were used as early as 1634, but the format was in no way standardized: Voters often simply wrote their candidates’ names by hand.

Election tickets from Massachusetts, from 1827 and 1829. Early paper ballots required voters to write their candidate preferences by hand.

American Antiquarian Society

As the population grew and the number of political parties, offices, and candidates expanded, election officials didn’t want to bother with the hassle and expense to oversee the production of all the ballots. By the early 19th century, parties were allowed to print and distribute their own party tickets, tightening their already firm grip on the electoral process. The party tickets listed their entire slate of candidates, forcing citizens to vote all or nothing.

So imagine: You arrive at your local polling place, where competing party heelers would exhort you to take their colorful, typographically distinctive ballot for you to deposit in a wooden ballot box, maybe accepting some ready cash in exchange. Poll watchers took note to ensure you submitted the right ballot, confirming the party’s money was well spent. Despite limited regulations in some states requiring ballots to be printed on black ink with white paper, the majority of election tickets from the period featured attention-grabbing displays of freewheeling typographic ornamentation, color, inks, and imagery. These ballots doubled as political advertisements.

Ballot backs from the 1860s. The backs of ballots were often even more colorful and outlandish than the business side.

American Antiquarian Society and the Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Party tickets offered a number of opportunities for creative forms of chicanery: One account from 1878 describes the “tissue ballot” used in some Southern states, where ballots were printed on stock so thin that they could be nested together, so that, once inside the ballot box, a shake would multiply them from one vote to many. Another gambit to pump up vote totals was voting “by whiskers”: A man with a full beard would deposit a ballot, then shave his beard to alter his appearance and vote again under a different name, repeating the process several times until cleanshaven.

Backs of ballots from the1860s. The backs of ballots were often even more colorful and outlandish than the business side. One ballot depicts the sinking of the CSS Alabama, a Civil War naval battle. Another has a visual aid for polling hours.

American Antiquarian Society and The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Ballots of the era may not have been ideal for a free and fair election—but they certainly were not boring. Intricate designs on the backs and a range of emblems represented the many political parties and factions of the day. Illustrations of chickens, stars, ships, fountains, and eyeballs at the tops of the ballots also served as identification aides for illiterate voters. Tickets also served as convenient pieces of propaganda: California ballots from the Workingmen’s Party featured blunt, anti-immigrant party mottos (“Exclude the Chinese!”) as well as xenophobic depictions of Lady Liberty protecting America’s shores from encroaching foreign labor. Ballots supporting anti-corruption reform during the Boss Tweed era graphically depict a citizen throttling a party boss.

Regular Democratic tickets and Regular Workingmen’s tickets from California from the 1880s. The wave of immigration during the 19th century motivated the formation of political parties based exclusively on anti-immigrant platforms. These ballots from San Francisco called for the “Exclusion of Chinese” and depict Lady Liberty holding back the immigrant hoards.

California Historical Society and the Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Concern is growing over the accuracy and auditability of modern digital voting systems, and whether they’re vulnerable to hacking. Ballot boxes of the 1800s—typically large wooden containers with hinged lids and multiple locks—were also subject to tampering. One box, discovered in San Francisco, turned out to include secret panels filled with pre-marked ballots. Transparent glass ballot containers were introduced as an antidote but were a limited success. The system was consistently vulnerable.

Sometimes it wasn’t one box, but many. As a deliberate form of voter suppression, South Carolina passed the Eight Box Law in 1882. Voters were required to place their ballots in separate ballot boxes, one for each type of office—any ballot cast in an incorrect box was disallowed. This functioned as an effective literacy test, clearly discriminating against the black population without violating the recently passed 15th Amendment.

A New York state ballot from 1895. The adoption of the Australian system in 1889 radically changed the form of the ballot: All candidates were listed on one ballot produced by the government, and votes were marked in secret. Despite these regulations, states began adopting variations with pictorial emblems that allowed for “straight ticket” voting.

New York Public Library

By the late 1800s, the public was getting fed up with the rampant fraud and called for a purification of the system. It took a while to take hold, but by the late 1880s, the American government adopted a format introduced in Australia around the 1850s: an official, government-issued ballot, distributed only at the polling place, regulated in its layout, and, above all, marked in secret. Detractors fought back: This “kangaroo vote,” they claimed, would be too expensive to print! The process of marking the ballot and all its individual choices would be too taxing! Voting in secret was cowardly! Despite this resistance, the Australian ballot was adopted by the turn of the century, marking the beginning of watershed election reform measures as well as the demise of freewheeling ballot design.

A 1972 sample ballot from Pennsylvania. As paper ballots were blamed for persistent fraud at the turn of the century, the adoption of voting machines resulted in the demise of freewheeling ballot designs. Mechanized voting proved less than foolproof.

Division of Political and Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Our contemporary democracy is still actively dealing with fundamental issues of voter suppression, harassment, misinformation, and fraud. But when you step into a voting booth, you can be confident that it will not only list the candidates from one party, it will be identical to those in the booths on either side of you. You are unlikely to face intimidation or bribery at the polls (unless you count the reward of a sticker as a bribe). And, most critically, your vote is secret. Ballots today may be graphically torpid compared with their historic peers, but perhaps we should be grateful for that.

These images and others will be featured in This is What Democracy Looks Like, out in May from Princeton Architectural Press.

Support This Work

Help us cover the central question: “Who counts?” Your Slate Plus membership will fund our work on voting, immigration, gerrymandering, and more through 2020.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3ckNHbS

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言