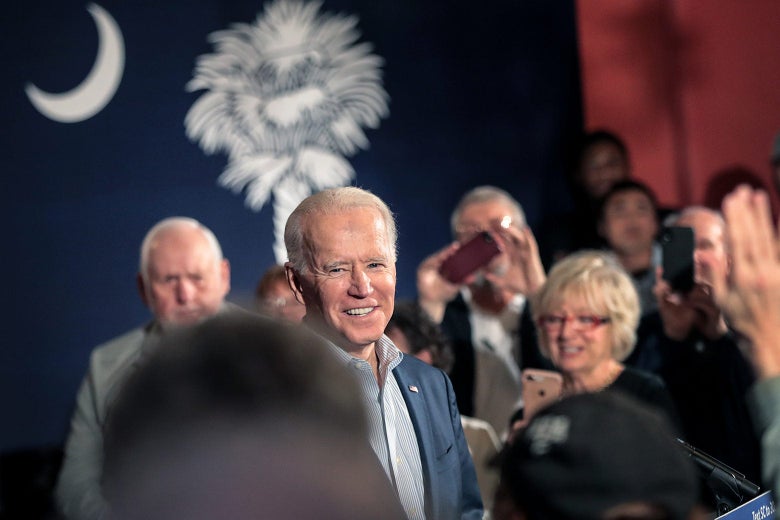

Joe Biden speaks to guests during a campaign stop at the Winyah Indigo Society Hall in Georgetown, South Carolina, on Wednesday.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

GEORGETOWN, South Carolina—Joe Biden needs to win South Carolina to keep his presidential hopes alive. He knows it. That’s why there wasn’t much risk for him, during Tuesday night’s debate, in setting a marker by saying he would win Saturday’s primary. If he gets it right, he’ll have correctly called it. If he gets it wrong, who cares? He’ll be finished anyway.

And barring a systemic polling error, it looks like he’ll get it right.

The Biden campaign has been having some of its best days of the early primary season—a low bar, sure—this week. A second-place finish in the Nevada caucuses gave way to a strong debate on Tuesday night, showing a vigor that was missing earlier in the year. The next morning he received an endorsement from South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn, the House majority whip whose reverence within the Congressional Black Caucus is exceeded only by that within South Carolina Democratic circles. The most recent polls of the state show him with comfortable leads over his nearest competitors, Bernie Sanders and Tom Steyer, the latter of whom had been eating into Biden’s base of support with an overwhelming advertising blitz. A fabrication that might have ended his campaign in another era, hasn’t picked up much damaging traction in the era of Donald Trump.

If the firewall can hold a few more days, it’s because South Carolina is just not a state that allows whoever is coming in with a head full of momentum to roll through and pick up another victory. Candidates with little connection to black voters, who make up about two-thirds of the primary electorate, will not find success by popping into a black church a couple of times or speaking about the need for criminal justice reform. And, yes, the candidates who served as Barack Obama’s vice president for eight years will have a stronger foundation than those who did not.

The scene on Monday, at the South Carolina Democratic Party’s First in the South dinner at the Charleston Marriott, was a sharp reinforcement of something that’s both obvious and needs to be said often: Democrats are not in Iowa or New Hampshire anymore. It was not the perfect cross-section of the state primary electorate, as it was, after all, a fundraiser. One of the loudest laugh lines of the night came from Clyburn, who told the crowd that he had been going to the First in the South dinner for so long that he could remember when it cost only $25 to attend.

The crowd was about equal parts black and white and, except for a table here or there, not particularly receptive to revolutionary politics or to candidates who had staked their first year of campaigning on Iowa with little regard for what came next. The first thing Bernie Sanders said, after a cordial reception, was that he recognized there were differences of opinion in the room, and he went from there to defend his own electability. His argument that he could put Texas in play in the general election, judging by the limited applause for a line that might have given him rapturous applause at one of his own megarallies, didn’t pass the smell test.

Pete Buttigieg’s acknowledgement that white candidates too often only reach out to black voters around elections, and then take them for granted, came across less as a humbling appeal than a spotlight on exactly what he was doing at that moment. Amy Klobuchar’s closing line—“I know you, and I will fight for you”—was at least half-wrong, and she still seems to be learning that audiences here don’t care that she launched a presidential campaign in a snowstorm. Even Tom Steyer, who has gained some traction over his fellow also-rans, earned a few eye-rolls when he enthusiastically mentioned how he was the only candidate to call for reparations.

Few lines from the presidential candidates earned as much applause as the ones from Rep. Joe Cunningham, a freshman Democrat representing a targeted low country district, did when he called for “pragmatic” and “mature” leadership in Democrats’ presidential choice.

About midway through the program, those attendees who had been politely eating their plated dinners of chicken and fish during other candidates’ speeches stood up with their cameras when Joe Biden came out. (He was called on stage by SCDP Chairman Trav Robertson, who introduced him as “the only person who has ever eulogized two United States senators from the same state.” Robertson named one, Fritz Hollings, but stopped short of naming the other.)

Biden barely said anything, speaking for only four of his allotted 10 minutes. Most of that was devoted to aggrandizing and touting his relationship with Clyburn. (The shortness of his remarks, judging by the way he pointed to Clyburn to emphasize his brevity as he was walking offstage, seemed to be in Clyburn’s honor.)

And even in that short amount of time, he managed to screw up the big ask: “My name’s Joe Biden. I’m a Democratic candidate for the United States Senate,” he said. “Look me over, you like what you see, help out. If not, vote for the other guy. Give me a look though, OK?”

He left stage to a standing ovation.

“Everybody in South Carolina loves Joe Biden. They may not say it, but they love him.”

Denise N. Washington, a black woman from Georgetown, was “100 percent committed” to Joe Biden since the day he entered the race. She had staked out the seat immediately in front of his podium on Wednesday at an event Biden was doing in Georgetown, about an hour north up the coast from Charleston. She was dressed sharply for the occasion, wearing one of the custom hats she had designed, a hobby for which she’s become locally famous.

“I’ve always been a Biden supporter. You know, Biden supporter, Obama supporter.” She appreciates him looking out for people with disabilities, as well as his positions on Social Security, health care, gun control, and education.

“I love everything that he stands for,” she said.

The event began with the Pledge of Allegiance and a prayer from a local pastor who prayed for Biden, his campaign, and an “overwhelming turnout to vote.” It was left, then, to state Rep. Carl Anderson, who represents Georgetown, to address the latest statewide scuttlebutt. He spoke about how some nefarious upstate conservatives had been calling on Republicans to vote for Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary on Saturday, “because they know that our vice president, Joe Biden, is the strongest candidate in this race.” And without saying a name—because there was no need to—he addressed the issue of Tom Steyer spending an exorbitant amount to peel away Biden’s base.

“Tell your friends, who are trying to get you to go the other way because the billionaires and the millionaires are dumping money into South Carolina, listen: We’ve got the right person in Biden,” Anderson said. “Doesn’t have a lot of money, so guess what—he’s on our level, right? I got you? So he’s our friend, right?”

In his speech and the question period that followed, Biden touched on education, Social Security, a push to dredge the Port of Georgetown, rural broadband, climate change, and gun violence. Much time was spent, too, discussing how “Barack and I,” alongside Clyburn, secured votes for landmark health care legislation—“Obamacare,” not “the ACA”—that Sanders would rather do away with in favor of something else. The Q&A was a typical question period for Biden: Questions weren’t entirely questions so much as prompts for him to speak haphazardly, and at length. Anderson politely tried to cut him off after a while by starting a round of applause, and Biden said he would take two more quick questions.

Neither Biden’s speech nor the questions he got dealt with what is so often defined as the one “racial issue” in cable news discussions about, or presidential debates in, South Carolina: the criminal justice system. The frustration with that narrow scope is palpable among black voters. As Rep. Ayanna Pressley, a surrogate for Elizabeth Warren, told reporters before the debate Tuesday night, “People are lazy, often, and come into our communities and just talk about the criminal/legal system.” Biden doesn’t talk to black voters with the pathos that so often can be a tell. He’s not, after all, just introducing himself.

“We are sick and tired of it,” Anderson told me afterward about the way certain other candidates have campaigned for black votes. “He is here, and he’s not coming stating something that he has not already done. When you follow his record, he has always been here to help minorities.”

Steve Williams, a journalist and author who’s written a book about black Americans in Georgetown, was also in the audience. He doesn’t think Biden is “a great debater” and didn’t like how Biden complained during Tuesday night’s debate when he didn’t get time to speak. But he’

“He and Obama, their administration, it was a team administration,” he said. “And I feel a sense of pride when I think of Joe Biden because, No. 1, Obama picked him.”

Slate is covering the election issues that matter to you. Support our work with a Slate Plus membership. You’ll also get a suite of great benefits.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2wRhHvL

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言