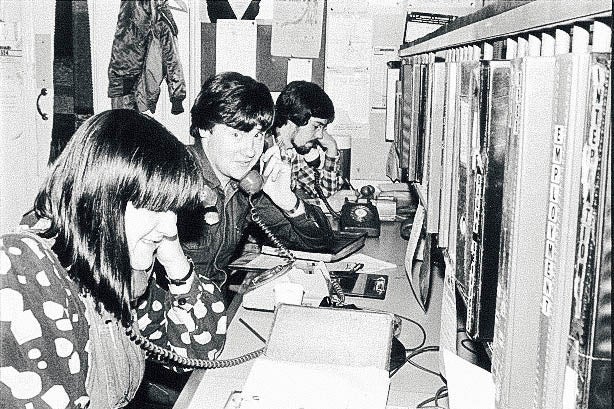

Operators working for the Switchboard in London in the 1970s.

Switchboard photo archive

This post is part of Outward, Slate’s home for coverage of LGBTQ life, thought, and culture. Read more here.

Although the U.K. has a rich queer history of its own, it doesn’t have a moment as singularly important as the Stonewall uprising in America. Perhaps those hot nights in Greenwich Village in 1969 have come to loom so large because Americans are so good at telling their own stories, over and over again. Brits, on the other hand, are more likely to mumble, “Yeah, some things happened … ”

But we do have plenty of stories to tell—especially from the lives of the people whom we now refer to as LGBTQ. And I don’t just mean from our more famous luminaries, like Alan Turing. British LGBTQ history can also be remembered through the stories of the countless other, more mundane individuals who endured persecution or thrived as unashamed queers.

On April 9, 1978, a young carpenter named Paul was discharged from hospital after surviving a suicide attempt. Destitute, he phoned a help line to ask if there was somewhere he could stay. The volunteer who took his call at the Gay Switchboard recommended a few hostels, according to their note in the logbook from that shift. “Also suggested that he should come back to us a bit later this week to find a bed-sit,” reads the entry.

I don’t know what became of Paul, but I hope Switchboard fixed him up with one of the people who frequently offered a place to stay when they had a spare bed. A logbook entry from 1975 reads:

Crashpad offered in SW1 [a London postcode]. This is not operational till caller confirms date. Ringing back within a month when his flatmate moves out.

These handwritten logbooks offer a unique glimpse into the U.K.’s queer history. The help line started in 1974, partly to draw on the energy generated by the American Gay Liberation Front in the early ’70s. Volunteers set up the first phone line in the basement below a socialist bookshop in Kings Cross in London. They surely could not dream of the freedoms that were to come to LGBTQ people in the next few decades, or that Switchboard would still be taking calls in 2020.

The shelves of the archives of the Switchboard logbooks, seen in London in 2019.

Imogen Forte/The Log Books podcast

A new podcast, The Log Books, uses the volunteers’ extraordinary handwritten archive to tell these stories. As a co-producer of the podcast, I read through hundreds of pages of notes and interviewed dozens of people to collect their memories. Like Paul, so many of the people with stories had nowhere to go. Here is an entry from June 11, 1982:

I had a call from a 19-year-old TV [transvestite] in Ashford who had been thrown out of home this evening by his parents who had just “discovered” … Luckily he seemed reasonably together about his situation and was reconciled to spending a night in his Mini.

Sali, one of the interviewees for the podcast, wasn’t thrown out of home—but she did leave, while only 16, in the 1970s. “I’d had enough because my mum was physically and emotionally abusive,” she says. “So I packed a carrier bag and I went to social services.” Sali was boosted by a call to Switchboard, during which a volunteer assured her that other lesbians existed. “The main thing I wanted to do was to talk to somebody who was like me, to know I wasn’t on my own, I wasn’t from another planet,” she says. “I wanted to feel less isolated.”

The logbooks show that Sali’s reason for calling was incredibly common. And Switchboard volunteers helped in many other ways, often with tips on where to go out. They kept meticulous notes on pubs and clubs:

April 19th, 1975—Chagueramas reported not gay at all. Straights have been making comments when gays dance together.

December 17th, 1975—A woman caller asked if there was anywhere for women to go after 11pm.

As in America, pubs and clubs in the U.K. play a huge role in queer life, today and historically. The Coleherne pub in West London served men in leather on one side of the bar and sophisticated queens in Angora fur sweaters on the other. Although, in reality, the tastes in that pub mixed more than clothing might have hinted. Neville remembers the leather side of the Coleherne like this: “Someone once said to me, [that] in that group you often hear some of the best criticism of what’s on at the opera house. And it was true.”

That is the level of community knowledge that Switchboard volunteers needed to have. They devised a system of maps with color-coded pins so they could easily locate intel on different parts of the country when someone phoned with a question. “You had to leap up,” says Femi, a former volunteer, “and your geography had to be good. ‘You’re in where? Oh, OK! Weston-super-Mare? Nope sorry, there’s nothing there!’ ”

They also had to keep track of “cottages.” In British queer history (and still today), a cottage is a public place known for cruising, usually a public toilet. Cottages are full of stories, as Julian remembers in the podcast. “It was easy to stand around or wander around the toilets in Waterloo station. You didn’t have to pay 10 pence just to get in. … So you went in there and sat down and moved your feet further and further apart so your shoe could be seen under the cubicle next door. And if somebody moved their feet towards that as well, then you could start knocking each other’s feet—and then you knew.”

But this was risky business (surely part of the attraction), as recalled in the logbooks:

February 13th, 1976—The cottage on the third floor of [the department store] in Oxford Street is very dangerous at the moment. Staff or plain clothes police watching everyone and looking under cubicle doors.

These are some of the most upsetting stories from the U.K.’s recent queer history. Police forces across the country organized to pursue men for having sex with men, often entrapping them in well-known cottages with handsome officers in shorts. It happened well into the ’90s. “It was all rather scary,” recalls one contributor to the podcast, about how men were arrested in parks. “You were told, ‘I’ve got a big torch in my pocket and if you make the slightest move to get away, you’ll get it across the neck.’ ”

Defendants often found lawyers by calling Switchboard. “People were very anxious about their careers, their reputation, often about their family circumstances and what the consequences of a conviction for gross indecency would be,” says David Offenbach, one lawyer who frequently defended men under such charges. “Often some of these conveniences [toilets] had been set up in a way, or adapted, where it was easier for the police to convict. So if there were holes in the wall, [or] places where a police officer would be concealed, there would tend to be more cases from those conveniences than from others.”

Convictions stick. Thirty-eight years after he was arrested in a public toilet, even though he was alone, Terry is still branded a criminal. “If I go for a job or to join an organization that wants to know if I have a criminal record, I won’t get past the front door,” he says. Turing famously received a pardon for similar offenses, in 2014—but only under the queen’s royal prerogative of mercy. It neither expunges his record nor declares that the law that condemned him was unjust in the first place. The government later created a system for other people, like Terry, to have their convictions disregarded. But the law is so narrow that only 189 convictions have been disregarded, out of a possible 50,000. Terry is one man who remains convicted of this historic offence.

Terry’s story shows how history lives with us. Stories abound in the bureaucracies of the justice system and the archives of organizations like Switchboard. But more importantly, they exist in the memories of our queer elders—people like Terry, Julian, Sali and Femi. You might walk past any one of these in the street and never hear the stories they have to tell.

Our history is a mess of stories, and queer life today is often just as perilous as it was in the past. One of the startling things about the stories in Switchboard’s archive is how similar some of them sound to tales from today. That’s why it’s crucial to listen to our elders, and and it’s my motivation for working on the podcast The Log Books. History is not just a series of events, or breakthroughs like Stonewall. It is still surrounding us, as a soundscape of shouting, laughter, crying, and singing.

For more info about the podcast The Log Books, including where to listen and subscribe, visit www.thelogbooks.org.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2vd2Z1g

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言