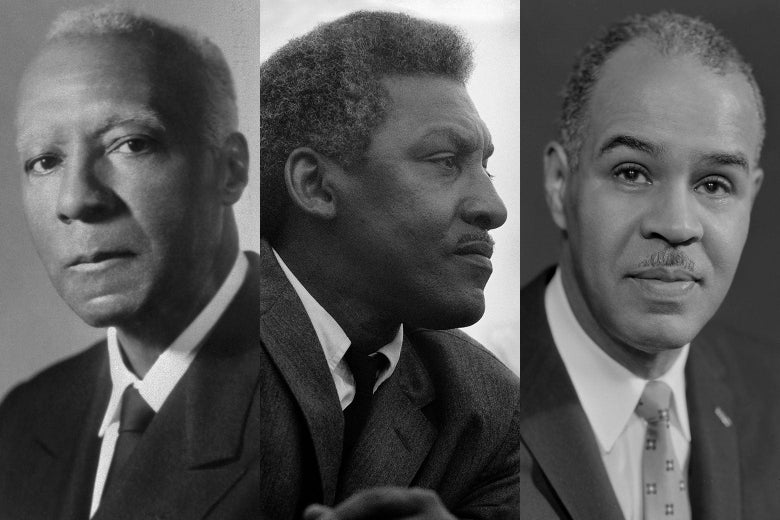

A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Roy Wilkins.

Photos by Bettmann/Getty Images, Stephen F. Somerstein/Getty Images, and Bachrach/Getty Images

When the internet turned 50 last year, there was much to celebrate. It proved to be a powerful platform from which to mobilize millions to fight for racial, economic, and social justice, through movements such as Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, and Black Lives Matter. It has also given us a million different ways to escape, chill out, and give ourselves a much-needed break—from cat videos to Cookie Clicker (where I have amassed more than 55 million cookies in just the past week alone).

But the anniversary also gives us a reason to reflect. Computing and the internet have not been the engine of democracy and economic opportunity we once dreamed of. Rather, they have become a breeding ground for racism, discrimination, and economic inequality.

How did we get here? That was one of the questions I set out to answer five years ago when I started researching my new book, Black Software. That’s when I embarked on an unpredictable journey that led me back to the 1960s civil rights movement—and blindsided me.

You see, my schooling on civil rights–era history runs fairly deep. Mrs. Crume taught me sixth grade Texas history. She was Black. Thin. Regal. I imagined her to be nearly 100 years old. I don’t remember much of my Texas history canon. But her class is where I first learned of Jim Crow. Segregation. Civil rights. Mrs. Crume delivered those lessons through stories about her and her husband, Arthur Crume, the one-time frontman for the legendary gospel/soul group the Soul Stirrers. She narrated his rides throughout the “chitlin’ circuit,” a network of performance venues that provided shade for Black performers at a time when their movement throughout the South was suspect, dangerous, even deadly.

My civil rights education continued in graduate school, studying with the first Black professor the University of Oklahoma had ever hired, back in 1967. George Henderson was a civil rights pioneer. He stood alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Received the former’s counsel. Respectfully declined the latter’s recruitment.

Then, for 15 years I studied how U.S. political campaigns frequently undermined our ideals of (racially) representative government. That demanded I understand what many scholars had written about the civil rights era.

But around 2016, I found myself back in the middle of the 1960s, hunting for an answer to a technology question. That is when I confronted the fact that I didn’t know as much about the civil rights movement as I had thought.

The 1960s—that was the explosive decade when the computer revolution and the civil rights revolution collided, catapulting us toward our current moment. But I also discovered that in the 1960s, our civil rights forebears, not the computer wizards, were the ones highlighting the challenges such innovation would bring. Those civil rights figures provided a blueprint for not just their own technology future in the 1960s, but our own future that we must confront now.

Many of the computer scientists and engineers of the day seemed indifferent to the civil rights movement. However, three civil rights figures—the philosopher, the planner, and the visionary—were keenly aware of, were concerned about, and directly addressed the growing revolution in computing and automation.

A. Philip Randolph was a labor leader. But when it came to the subject of automation and technology, he was our chief ethicist. Randolph never shied away from a good fight, but he thought it foolish to resist technology’s progress. “You cannot destroy the machine. You cannot stifle the invention of various geniuses in the world,” he once said. Still, Randolph outlined key principles that should govern technology’s design and use. To Randolph, technology wasn’t just the domain of technical experts or privileged classes. Technology, he asserted, was the “collective creation of the people.” As such, he believed “the people should share in the fruits of technology.”

As the longtime head of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Randolph was primarily concerned that automation would displace Black workers. But he was no Luddite. He simply believed that public interest should govern and guide technology. He stressed that “the community and the government have a responsibility” to see that technology produced public goods.

Will we focus our attention on ameliorating racism and providing equal opportunity, rather than merely trying to excise bias from technological tools?

In that vision, Randolph gave us a model for technology governance. But it was Bayard Rustin—architect of the famed March on Washington—who developed a plan. Rustin knew that automation’s employment threat was merely a symptom of a more deeply rooted problem: America’s antipathy toward Blackness. Rustin knew that negative consequences caused by automation would hurt Black people first and hardest. But it was precisely this certainty that led Rustin to see a way forward—through planning.

Rustin was aware of not just automation, but cybernation (a term used in the 1960s to refer to both computerized automation and that era’s concept of “artificial intelligence”). Automation referred to computers carrying out industrial processes. Cybernation emphasized a sense that computers could “learn”—and therefore get “smarter.” Rustin realized that we needed to educate and prepare people socially, emotionally, and vocationally for the latter rather than the former, such that Black people would “keep up” with the computer. But Rustin also knew that this was a difficult proposition. He knew that racial discrimination in employment was real and rampant. But he believed we faced a more fundamental problem.

At the time, many corporate do-gooders and government bureaucrats alike rushed or were dragged into reforming America’s ghettos. They said job training is what Black folks needed, and needed immediately. But Rustin wasn’t concerned about Black people’s present economic condition when he spoke about “Humanizing Life in the Megalopolis” in 1965. He was concerned about their position in 1995 and 2015. Rustin argued that the narrow focus on short-term job training as a solution to racial and economic inequality bred disillusionment, anger and contempt in Black men and women. “We are giving them an aspiration which this society cannot fulfill, and the reason is we reject planning,” he said. Rustin believed that we should think, calculate, and plan for and over the long term. That, he argued, would guarantee that Black people were full and equitable stakeholders in a new computational society.

Randolph was technology’s moral compass. Rustin its would-be social engineer. But Roy Wilkins was its civil rights visionary. Wilkins once hoped to become an engineer. He became a journalist instead, then a writer, then an organizer, the latter two during his decades serving the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Wilkins didn’t have an MIT degree. He didn’t know much about the inner workings of word processing (which was still considered women’s work in his day). In fact, the closest Wilkins seems to have come to an actual computer was making requests to IBM: first, to remove one of its outdated 020 Key Punch machines from the NAACP offices; second, to ask for more punch cards to facilitate address labeling for an upcoming NAACP membership drive. The NAACP, like other organizations and businesses of the day, utilized the day’s computers for what they were: simple tools to make work and work processes more productive.

Beyond the organization’s practical use, however, Wilkins thought deeply and frequently about the consequences that computerization would one day have on Black lives. He, too, was concerned that automation was the latest technology white people would use to keep Black people in their place.

He was also concerned about representation. A New York newspaper once showcased what Wilkins called a “standard riot photograph” (Black people looting). Wilkins connected the problem to a new shoplifting database that Spartan Industries—a retail company—had developed for New York’s Alexander’s department store. Wilkins feared that computers used to identify thieves in stores would import, and build into their memory, the stereotype that Black people are criminals. He feared that such computers would be turned into racial profiling machines, used to target and jail Black people.

Wilkins had many other concerns about the computer. But mostly he saw that we were not using it as we should. If the computer was as powerful as we thought it to be—if it was a great problem-solving machine—then could we not ask it to help us overcome that problem that lies at the heart of American society? The problem that predated the computer itself?

Wilkins asked it this way in a 1967 Los Angeles Times opinion piece titled, “Computerize the Race Problem?”

After the computer has defined, on tape, the ideal Holstein, could it then turn its impersonal, unprejudiced magic upon our agonizing race problem? Could it not, after digesting the facts which both whites and blacks have fogged over for so long, give us an outline of our obligations? Instead of being a measure of the Negro’s lag, cannot the computer become a guidepost to interracial justice and peace?

Unfortunately, in 1967, no one took this question seriously, and, as Rustin predicted, we rejected the opportunity to plan for Black people to have a stake in the computer revolution that was taking place in (and since) 1965. Similarly, Randolph’s technology governance principles were largely ignored from the day he proclaimed them. Had we heeded their words, there would likely be more Black, Latino, and Asian folks in, and in higher levels of, leadership and ownership in today’s computing industry. We would likely have fewer of those same folks in the criminal justice system today as well.

We stand more than 50 years removed from Randolph’s, Rustin’s, and Wilkins’ sage advice. As we look forward to the next 50 years of technological innovation, will we reconsider? Will we seriously heed the admonition to plan so that people of color will have a share of, and stake in, our technological future? Will we work to determine what it would take to educate technologists of color to work in today’s and tomorrow’s tech industry and governance structures? At every rung of the ladder? In the same proportions in which we exist in the population? Will we plan to make measurable progress toward meeting this goal in the next 10, 20, or 50 years? Will we commit the long-term educational, public, and private sector resources needed to achieve such a goal? Will we focus our attention on ameliorating racism and providing equal opportunity, rather than merely trying to excise bias from technological tools?

If we do not, then we can certainly predict that the most marginal and vulnerable among us will continue to get crushed under the weight of our next technology revolution.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/314BNxA

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言