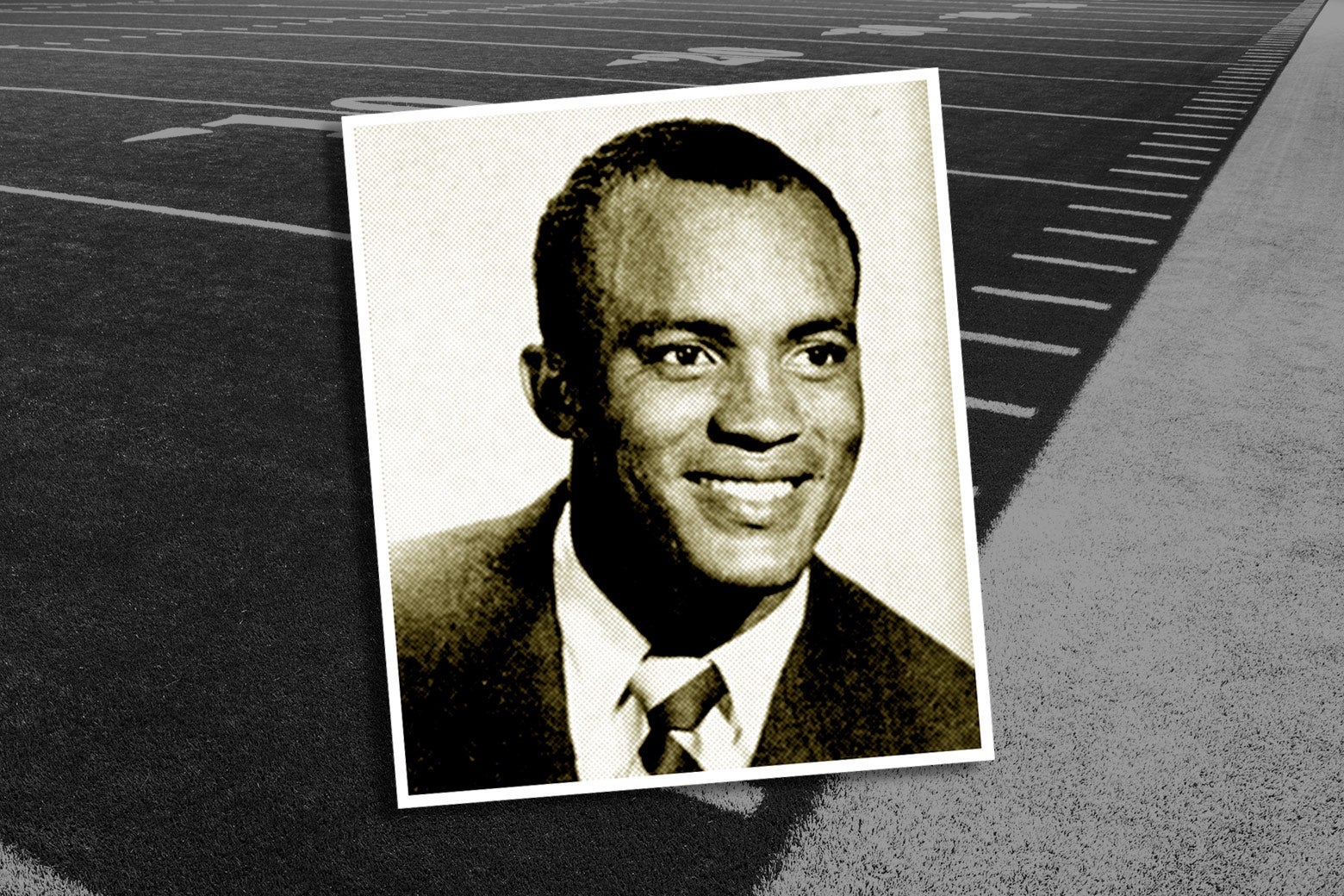

Rommie Loudd

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Wikimedia Commons and PhotoAlto/Sandro Di Carlo Darsa/Brand X Pictures via Getty Images Plus.

In September 1971, reporter Pat Horne of the Boston Record American had a big, back-page scoop. “EXCLUSIVE,” the headline blared. “Black Group to Petition NFL for Franchise as the ‘Memphis Kings.’ ”

The story was filled with remarkable details. The team would be located in Memphis, with “strong sentiment” to name it after Martin Luther King Jr., who had been slain in the city three years earlier. Sammy Davis Jr. and Sidney Poitier were involved. The group planned to solicit financial support for the estimated $12 million to $14 million expansion fee from the Martin Luther King Jr. Foundation and black-owned businesses, including Ebony magazine, Parks Sausage, and Johnson Products Co. It was even thinking about asking for help from President Richard Nixon, “who is an avid football fan.”

Top jobs would be filled by black NFL veterans. Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown and tight end John Mackey, the head of the league’s players’ union, were being considered for president. A list of potential coaches included Eddie Robinson of Grambling and Emlen Tunnell, a New York Giants assistant.

Cultivating the first black-owned team in pro sports, Horne wrote, would be “an incredible coup for the National Football League that prides itself in the total lack of racial problems within its ranks.” In the black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier, columnist Bill Nunn Jr. wrote, “How the whites would react to a black owned team remains questionable” but “[t]his dream of a black owned franchise is no longer a fantasy.” Another sportswriter predicted that black people across the country “will become avid rooters” and black players “will want to be traded to the new club.”

The NFL wasn’t as enthusiastic. The day after the Record American report, a league executive denied any knowledge of the effort. He said there was interest in Memphis to launch a franchise—the Boston Patriots and New York Jets had just played a preseason game there—but the NFL had no current plans to expand.

The Sept. 9, 1971, issue of the Boston American Record.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Boston American Record (screenshot).

Horne never followed up on his story—he left journalism not long after to become PR director for the Patriots—and the Memphis Kings disappeared from the news. But the idea of a black-owned team didn’t go away, thanks to a Patriots executive mentioned in Horne’s original article.

Rommie Loudd was an All-American tight end at UCLA in the 1950s who played professionally in Canada and later for the Patriots. He became the first black coach in the American Football League, with the Patriots, and then the team’s first black front-office executive. (The Patriots joined the NFL after the merger with the AFL in 1970. The team moved to Foxborough from Boston and changed its name to “New England” in 1971.)

In Horne’s article, Loudd wouldn’t confirm or deny knowledge of the plan, but he was almost certainly its source. A year later, in August 1972, the Tampa Tribune reported that Loudd and Jim Brown had met with officials in Orlando, Florida, about a black-owned team. Orlando officials were told, the paper said, “that Brown has demanded and gotten such a promise out of Commissioner Pete Rozelle and that it can be done.” The NFL denied that, too.

Loudd went public that winter, telling the Boston Globe that he planned to meet with Rozelle to pitch his plan for an Orlando team. “I know some people will call me a ‘nigger.’ But that won’t bother me. I know what I am and I know what I can do,” Loudd said. “Blacks have broken all kinds of barriers in sports. We’ve proven we can do the job in almost every area. This is the last step.”

His words seemed to have some impact. “We’re going to have to pace the problems of minority ownership,” Rozelle said before NFL ownership meetings a few months later. (Pace in this context almost certainly means “to set an example for” or “lead.”) “Forty percent of the players in the league are black,” the commissioner said. “Yet we have almost no blacks in front office positions. We will have to seriously consider that when we determine our expansion plans.” Rozelle said the league might need to practice “discrimination in reverse” to add minority ownership.

“Blacks have broken all kinds of barriers in sports. … This is the last step.” — Rommie Loudd

The idea of a black-owned NFL team came at a time when black athletes were “transitioning away from this activist model to a [financial] power model,” says Louis Moore, an associate professor of history at Grand Valley State University, whose tweet about the Memphis Kings on Martin Luther King Jr. Day led me to the story of Loudd. In 1966, Jim Brown formed the Negro Industrial and Economic Union (later renamed the Black Economic Union) to assist the growth of black-owned businesses. In 1970, Jackie Robinson was approached about the possibility of bringing a black-owned team to Major League Baseball. (Robinson wasn’t interested.)

But Loudd’s plan for a black-owned team in Orlando ran into obstacles. By mid-1973, his group was called the Florida Suns—not the Kings—and his investors were white businessmen. Loudd’s ambitions generated lots of local publicity, but he wasn’t able to negotiate a stadium plan. In February 1974, the NFL narrowed a list of 24 expansion candidates to five. Orlando didn’t make the cut. The league awarded teams to Tampa and Seattle.

Bill Clark, the sports editor of the Orlando Sentinel-Star, suspected that racial bias had blunted Loudd’s effort. Loudd persisted, though, immediately acquiring a team, the Florida Blazers, in the startup World Football League. The Blazers were a massive failure: They amassed more than $2 million in debts, bounced checks, missed player payroll, and were sued by partners and the league. One investor kicked the team out of its Holiday Inn offices. Loudd accused the city of overcharging for services and accused the community of racial discrimination. “If I’d been a white man, things here the past two years would have been somewhat different,” Loudd said. The Blazers lost to the Birmingham Americans in World Bowl I, 22–21.

Loudd was ousted as managing general partner of the team. But things would get much worse. Two days before Christmas, he was arrested on charges of embezzling state taxes from Blazers ticket sales. In March 1975, just before that trial was to begin, the Sentinel-Star splashed a headline across Page 1: “DOPE CHARGE ON LOUDD.” The paper described a “cocaine smuggling and sales ring that operated in at least three states.” It said the charges were the result of a six-month investigation that began with a probe of drug use by Blazers players. It said law enforcement officers feared that Loudd had been tipped off and had “fled to Zaire, in Africa.”

The March 10, 1975, issue of the Orlando Sentinel-Star.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Sentinel-Star (screenshot).

In a breathless follow-up story, the Sentinel-Star, quoting unidentified law enforcement agents, said the drug operation had outposts in Miami, Boston, New York, and the Bahamas. Loudd and his accomplices were “moving pounds of the stuff in lobster crates,” the paper alleged. The county sheriff’s department undercover agent who cracked the case was described as a “supernarc” engaged in a “cat-and-mouse game” with “the man”—Loudd, who had brokered the sale of a small amount of cocaine but promised much more. The story implied that Loudd could have had people killed.

The official case against Loudd was far less salacious. He was convicted of arranging the sale of 4 ounces of cocaine for $4,800 in Florida and a smaller amount of the drug in Boston. Loudd wasn’t present for the sales and never saw the money or the cocaine. Other charges, including the sales tax embezzlement, were dropped. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

In 1977, the Sentinel-Star reinvestigated the case and its own reporting and found both lacking. In a lengthy story in its Sunday magazine, the newspaper said it couldn’t prove Loudd was framed. But it quoted a Blazers investor saying an investigator told him, “We’re gonna get that black s.o.b. one way or another.” It also quoted from surveillance tapes showing the agent, posing as a businessman, telling a financially desperate Loudd that he and friends could invest up to $1 million in the team—and pressuring Loudd to get cocaine.

Loudd told the Sentinel-Star that he’d been entrapped. “He approached me—people must understand that—with the idea of investing [in the Florida Blazers]. And I end up with 14 years.” There were no promises of pounds of drugs, no international trafficking ring. “I tricked him, worse than I tricked anybody ever,” the agent told another officer on tape. The agent would later say that he meant he had outsmarted Loudd.

The Sentinel-Star admitted, tepidly, that it had regurgitated unsubstantiated police gossip. “The rather enthusiastic reporting of Loudd’s arrest appeared to contain some exaggerations, if not inaccuracies,” Sentinel-Star editor Jim Squires said in the magazine story about the case. In a separate column, Squires made a stronger point. If Loudd had been “a soft-spoken young white man, he could have bought and used four ounces of cocaine and no one would have cared,” he wrote. “But because Loudd was black, had a big mouth and made himself a ton of enemies he attracted the scrutiny others might have avoided.”

At the trial and in later interviews, the agent denied there was anything improper about the investigation. He was fired from the sheriff’s department in 1978. The sheriff who let him go said that he “no longer had any confidence” in him, explaining that the agent was “running amuck in the community.” The sheriff, however, said he “never had any second thoughts about the Loudd case.” (Messages left for the agent seeking comment were not returned.)

While Loudd was in prison, he admitted to reporters that he had used cocaine and chased women. There was something graver he did not discuss. In 1957, Loudd was convicted of “morals offenses involving teenaged boys” and sentenced to six months in prison. After the arrest, a black newspaper in Cleveland, the Call and Post, reported that three boys questioned by police said they were forced by Loudd and other men “to take part in sex activities.” “The trio stated that they were forced to take the ‘girl’ role,” the paper wrote. The Michigan Chronicle, another black paper, ran a banner headline on Page 1: “LINK GRID ACE TO SEX ORGY.”

The April 13, 1957, issue of the Michigan Chronicle.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Michigan Chronicle (screenshot).

Writers covering Loudd’s efforts in Orlando appear to have missed this aspect of his background. The first post-1950s mention of the “morals” case I was able to find came from a 1977 story in the Los Angeles Times about Loudd’s appeal of his cocaine conviction. That article said Loudd had served four months on a work farm for the sex offense.

“Because Loudd was black, had a big mouth and made himself a ton of enemies he attracted the scrutiny others might have avoided.” — Orlando Sentinel-Star

That conviction did not appear to affect Loudd’s football career, and he kept quiet about it going forward. The cocaine bust, he maintained, was simply a setup of a black businessman running a pro football team in the South. “They just wanted me out of the way, that’s why they framed me,” Loudd told Washington Post reporter Dave Kindred in a prison interview. “They didn’t want a black man to head up an organization that might be worth $25 million someday.”

Loudd served three years of his 14-year sentence for the drug conviction. He later worked in community development, hosted a sports show for prison television, and was an associate minister at a church in Miami. He died in 1998 at age 64.

Today the average value of an NFL team is nearly $3 billion. But the league still hasn’t been able to, as Pete Rozelle said back in 1973, “pace the problems of minority ownership.” The NFL has no African-American majority owners—let alone a black-owned team named for a civil rights icon—and there’s just one, Michael Jordan, in all of major North American pro sports.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2th6KlT

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言