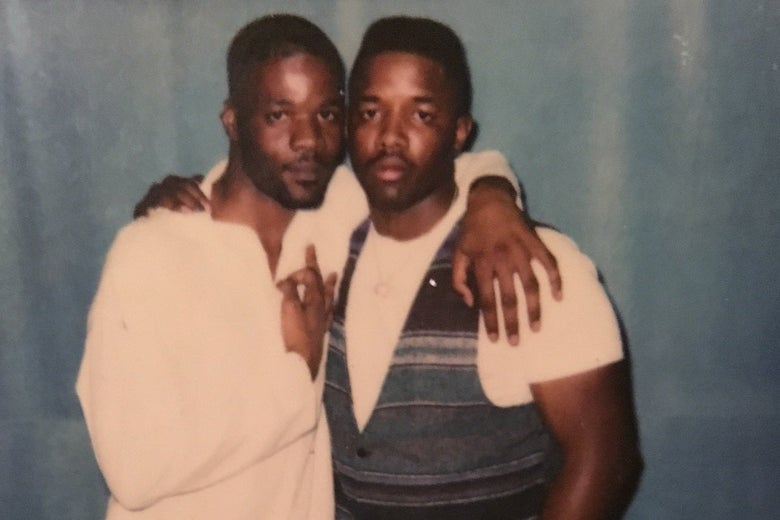

Ledell Lee, right, maintained his innocence up to the end.

Courtesy of the ACLU/Patricia Young

Three years ago, Justice Neil Gorsuch cast his first vote as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court to allow Arkansas to execute Ledell Lee for the 1993 murder of Debra Reese. In a 5-4 ruling, the court approved of the state’s decision to go through with a planned marathon of eight executions before a drug in their lethal injection cocktail was due to expire. There were serious flaws in the case against Lee, who unwaveringly professed his innocence. Family members offered an alibi for him during the approximate time of the murder. His first appellate attorney appeared drunk in court and never introduced evidence that Lee was intellectually disabled. In the days before Lee’s execution, Arkansas courts refused to allow a DNA analysis that could exonerate him. The decision by Gorsuch and the other conservatives to dismiss all this in the rush to use the lethal drugs was terribly controversial at the time. Lee was executed just before midnight on April 20, 2017.

That decision could soon look much worse. On Thursday, a group of lawyers, including from the Innocence Project and the ACLU, filed a lawsuit in Arkansas on behalf of Ledell Lee’s sister, Patricia Young, seeking testing of DNA and fingerprint evidence from the crime scene that the Supreme Court determined three years ago need not be evaluated. The five testable sets of fingerprints found at the scene do not match Lee’s, but can be tested against a database of 70 million people in minutes at no cost to the city of Jacksonville, Arkansas, one of the defendants in the case.

The lawyers are also asking for DNA testing from a host of other evidence. “There is a lot of physical evidence in this case that is very available for testing,” Cassy Stubbs, the director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, told me. That testable DNA evidence includes a hair that was found at the scene that a forensic examiner during Lee’s trial attributed to Lee using since-debunked hair analysis, a tiny spot of blood found on Lee’s shoe that prosecutors argued was likely Reese’s despite no other blood from the brutal scene being present on his clothing, fingernail scrapings from Reese, and a rape kit taken at the time.

The results of the lawsuit could be explosive. If a test excludes Lee’s DNA and identifies another suspect, it would be the first conclusive proof in the history of the modern American death penalty that an innocent man was executed. According to the Innocence Project, 367 innocent people have been exonerated through DNA testing. Since 1973, 167 death row inmates have been exonerated and released, 21 of them thanks to DNA evidence.

Death penalty advocates, such as the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, have used the fact that an executed man had never been definitively proven innocent to justify the death penalty. If advocates could show beyond doubt that a state has wrongfully executed an innocent man, it would expose those legal arguments as hollow and might seriously threaten the constitutionality of the death penalty.

In Lee’s case, Jacksonville initially cooperated with the ACLU, the Innocence Project, and Young’s attorneys in their efforts to collect information about the case, but, according to the ACLU and Innocence Project’s new legal filing, the new City Attorney, Stephanie Friedman, told them in Oct. that the city wouldn’t have the evidence tested without a court order.

That initial cooperation led to a series of revelations from top forensic experts that further weakens the case against Ledell Lee. For instance, a leading forensic pathologist, Michael Baden, says that an injury Reese suffered during her murder that was originally said to have come from a clubbing assault, likely instead came from the kick of a shoe that would not have matched the ones Lee was wearing when he was arrested, and which prosecutors said he wore during the murder. At the trial, prosecutors also claimed those shoes were a “slam dunk” match for footprints taken from the scene, but footwear examination expert Alicia Wilcox reexamined the materials with the cooperation of Jacksonville and determined there were serious flaws with the forensic analysis used. (Jacksonville Mayor Bob Johnson, who is named as a defendant in the suit, and Friedman did not respond to request for comment from Slate.)

The ACLU and the Innocence Project have also submitted to the court a sworn affidavit from Lee’s former appellate attorney, Craig Lambert, stating that despite his best efforts to support Lee’s case and his strong belief in Lee’s innocence, he had not been well-suited to handle the case at that time because he was “struggling with substance abuse and addiction in those years” including a time spent in in-patient rehab.

“I recognize that the investigation into Ledell’s innocence was not adequate and he deserved far better than the representation I was able to provide him back then,” Lambert said.

Even before this new evidence and sworn testimony, the case was already highly flawed. Lee’s first trial ended in a hung jury. At his second one, his lawyers did not bring up some of the potentially exonerating testimony and evidence raised in the first, including alibi testimony from Lee’s family members. In that second trial, a jury of 11 white and one black Arkansans—in a county where nearly one-third of its residents were black—found him guilty after a four-day trial and three hours of deliberation. The conviction came one week after the racially-charged O.J. Simpson verdict, and one witness alluded to that verdict by recalling a conversation she had “last week, when they let OJ Simpson go.”

“Big picture, this case is emblematic of so many of the failings of the death penalty,” Stubbs told me.

This is not the first time that groups have attempted to re-examine evidence from a crime scene using modern technology after an execution has taken place. In 2010, Texas re-examined crime scene evidence in the case of Claude Jones, who had been executed ten years earlier, with mixed results. Last month, a Tennessee judge rejected an effort to conduct DNA testing 13 years after the execution of Sedley Alley that might definitively prove his guilt or innocence. The Lee case may have a better shot, however, because it’s using the state’s Freedom of Information Act in order to pressure the city to re-examine crime scene evidence.

“Arkansas has a really strong FOIA and it has a really strong FOIA tradition and the Arkansas Supreme Court has upheld the really broad nature of Arkansas’s FOIA action,” Stubbs said. “We thought that this evidence should and is likely to be found to be open to this kind of inspection under the Arkansas statute.”

Stubbs argued that it should be in Jacksonville’s interest to know definitively who killed Debra Reese. “This is a very easy lawsuit for the city to agree to and we’re just talking about some testing that can let us all know the truth,” Stubbs said. “I have a hard time understanding how that’s not in all of our interests.”

Young, Lee’s sister, made a similar argument in a statement released by the ACLU.

“My family has been unable to rest for the last two and a half years, knowing that my brother was murdered by the state of Arkansas for a crime we believe he did not commit,” she said. “What happened to Debra Reese is horrible, and we keep her family in our prayers. But I was with Ledell the day this murder happened, and I do not see how he could have done this. If Ledell is innocent, then the person who did this has never been caught.”

“All we want,” she said, “is to finally learn the truth.”

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/38DadKB

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言