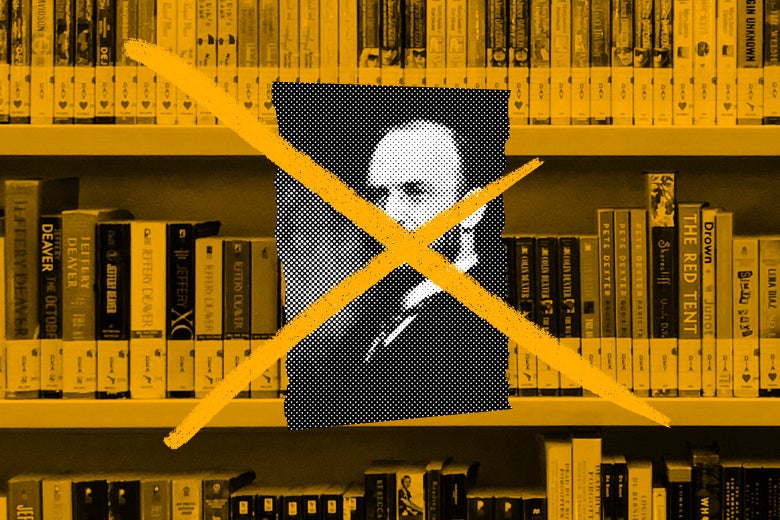

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Zaini Izzuddin/Unsplash and Oregon Government.

In June, the American Library Association stripped a familiar name from one of its top leadership honors: the Melvil Dewey Medal. As you may recall from grade school, Dewey was the man behind the Dewey Decimal Classification system, the schema of numbers and subject areas used at libraries around the world to categorize books. Founder of the nation’s first library school, co-founder of the ALA itself, and onetime director of the New York State Library, he’s usually revered as a library icon, his name perhaps the one most strongly associated with the institution. So what drove librarians to erase it from their own award?

As it turns out, despite the wholesome associations Dewey has accrued in the public imagination since his death in 1931, the man was no saint. And librarians, long considered hushed and hushing pillars of decorum, are no longer keeping quiet about his amoral behaviors.

The more sordid aspects of Dewey’s life may come as a surprise to modern readers, but they were public knowledge while he was living. Dewey was censured in 1906 by the ALA when several women complained about his improper behavior toward them—including unwanted kissing, hugging, and caressing in public. Dewey’s daughter-in-law even moved out of his home because she was uncomfortable around him.

In addition to Dewey’s sexism, the ALA resolution to drop his name, which was ratified unanimously by the organization’s governing council, also cited his anti-Semitism and racism. At a private club he owned on Lake Placid, Dewey did not allow Jews or blacks to become members or visitors. A club pamphlet read: “No one shall be received as a member or guest, against whom there is physical, moral, social or race objection. … It is found impracticable to make exceptions to Jews or others excluded, even when of unusual personal qualifications.” When news of the pamphlet became public, also in 1906, Dewey was forced to resign from his state library position. He defended himself, saying he had friends who were Jews, while also noting that a private club should be allowed to choose its members.

Members of the ALA addressed the Dewey dilemma as part of the organization’s annual conference. Sherre Harrington, coordinator of the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table’s Feminist Task Force, helped craft the resolution.

Harrington, also director of the Memorial Library at Berry College in Georgia, said she was surprised the ALA didn’t find Dewey’s past problematic until now. “It wasn’t like he’s being judged by 21st-century standards,” she said. “He was called out repeatedly for his sexual harassment behavior during his time.” But Dewey, she said, is considered a legend, “and people will say he’s responsible for making it OK for women to be in the profession.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 79 percent of librarians are women. And yes, Dewey might be partly responsible for that. When he founded the library school at Columbia University in the late 1800s, he advocated for women to be admitted as students.

He was hardly a feminist, however. In an 1886 speech titled “Librarianship as a Profession for College-Bred Women,” Dewey said that although women had the character and intelligence to be librarians (if they had a college education), they were also more likely to get sick or leave the profession to pursue “home life.” And women deserved smaller salaries than men, he said, because males, in addition to being capable of the same library work, could also “lift a heavy case, or climb a ladder. … There are many uses for which a stout corduroy is really worth more than the finest silk.”

In 1927, Dewey hired a stenographer whom he described (in “simple” spelling, which he championed because it eliminated extraneous letters) as a “dainty litl flapper” and “betr looking than I expected.” After he hugged and kissed her in public, she threatened to file charges and ended up settling with Dewey for $2,147.66. According to Wayne Wiegand, author of Irrepressible Reformer: A Biography of Melvil Dewey, Dewey was upset with the settlement not because he had been reprimanded for anything improper, but because he worried the stenographer might spread rumors that “she got $2,000 for no work.”

Similarly unrepentant after he was censured by the ALA, Dewey insisted he hadn’t done anything wrong. “Pure women would understand my ways,” he said.

Emily Drabinski, a librarian at the Mina Rees Library at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and an at-large member of the ALA Council, was present at the vote to ratify the Dewey resolution. The group’s unanimous vote surprised her. “I expected a lot more drama, but there was none,” she said. “People clapped and cheered; I was blown away.”

A partial impetus for the change was the ALA’s decision in 2018 to remove the name of Laura Ingalls Wilder from its top children’s author award due to anti–Native American and anti-black sentiment in her Little House on the Prairie series. (It’s now called the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.) According to Julius Jefferson Jr., ALA president-elect, in the post-Prairie aftermath, members began reconsidering other awards named after individuals who don’t meet the ALA’s current values. “Equity, diversity, and inclusion,” he said, have been a key focus of the ALA’s strategic plan for the past three years.

Jefferson said he can only speculate about why the ALA is just now reckoning with Dewey’s demons, but thinks the #MeToo movement might be partly responsible. “This profession is predominantly female, and we didn’t want an honor bestowed on someone tied to discrimination against women, African Americans and Jews—someone who didn’t recognize the humanity of individuals,” he said.

A 2018 article in American Libraries by Anne Ford titled “Bringing Harassment Out of the History Books: Addressing the troubling aspects of Melvil Dewey’s legacy” also influenced ALA librarians to take action against Dewey. Ford’s article questioned why Wiegand’s biography of Dewey did not create more of a stir when it was published 22 years earlier—by the ALA—in 1996. Unlike earlier Dewey biographies, Wiegand’s doesn’t whitewash his unsavory behavior.

“We didn’t want an honor bestowed on someone … who didn’t recognize the humanity of individuals.” — Julius Jefferson Jr., ALA president-elect

Wiegand, of Walnut Creek, California, and an emeritus professor of library and information studies at Florida State University, spent 15 years researching and writing the book. Dewey was “very self-righteous” and had a zeal for reform, Wiegand said. However, Dewey’s racism and sexism, he believes, has been mostly dismissed over the years as the actions of a “naughty boy who was the product of his time.” With the ALA’s action this year, that forbearance seems to be coming to an end.

What does this shift portend for Dewey’s intellectual contributions? The DDC might be the world’s most widely used library classification system, but like the man himself, it’s not without controversy. Critics say the subjects are heavily Eurocentric and favorable to Christianity. The 200s of the DDC, for example, are devoted to the subject of religion. But the subcategories are nearly all focused on Christianity, with one section for “other religions.”

Drabinski finds Dewey’s classification structure more offensive than any of his vices. “It’s all about white Christian power that has spread around the globe,” she said. “His personality pales in comparison to him as one individual dominating the structure of knowledge.”

Violet Fox, Dewey editor with the Online Computer Learning Center, which owns the rights to the DDC, said the system is continuously updated, and editors are now “focusing on gender identity and sexual orientation as well as providing new options for classifying works about Indigenous peoples.”

It’s unclear how quickly other library institutions will adopt the ALA’s new orientation toward Dewey. The Library of Congress has a brief webpage on Dewey that does not mention his sexism or racism, noting only that “[h]is legacy is complex.” “The OCLC wants the classification system to stand on its own without the negative parts of Dewey’s life,” said Caroline Saccucci, Dewey program manager at the Library of Congress. A previous version of the biography on the website, she said, “was actually much more complimentary. OCLC decided to neutralize it to lessen the complimentary aspect, and the Library of Congress followed suit.”

As for the ALA leadership medal, the resolution was sent to an awards committee that will recommend a new name for the honor, likely at the organization’s meeting in January. (The ALA has yet to reflect the name change on its website, which still refers to the “Melvil Dewey Medal.”) Harrington, the librarian involved in crafting the resolution, said she hopes the committee will come up with a name more befitting the honor, something that reflects the ALA’s “groundbreaking role in this country promoting the democratic sharing of information and intellectual freedom.”

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2nbe9zQ

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言