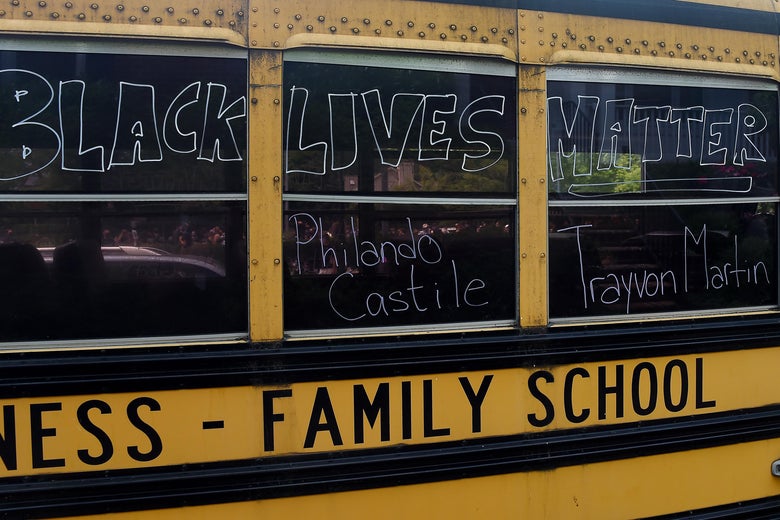

OLIVIER DOULIERY/Getty Images

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, schools across the United States have been soul searching over their complicity in enabling systemic, police-inflicted violence. Just this week, after years of local activism, the Minneapolis Public School board voted to terminate its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, ending its in-school installation of police officers known as “school resource officers” (SROs).

This is welcome news to critics of the school-to-prison pipeline, for the mere presence of SROs can change the course of a teenager’s life. One study in Connecticut, for instance, found that black and especially Latinx students were far more likely to be arrested and funneled into the criminal justice system—as opposed to simply being disciplined in school—when there was an SRO. Other reports have documented excessive uses of physical force by SROs. These officers have also become symbols of safety in school shootings, and some have faced off against gunmen and saved lives. Students of color nevertheless have continued to feel uniquely unsafe under their watch.

The discontent over SRO programs has intensified in recent years, but challenges to these programs have been lodged since they started spreading in the 1960s. Like opponents today, the earliest dissenters hated the idea of shifting school responsibilities to policemen. But their main gripe was that police officers might be free to interrogate students in ways that exceeded procedural due process norms. The new wave of opposition recognizes that reforming procedures in SRO programs may not be enough, that the mere installation of officers already dooms students of color from the start. Minneapolis was among the first cities to bring police officers into schools nearly six decades ago. The school board’s decision to remove them now reflects how dramatically the terms of debate have shifted.

The first major police-in-school programs cropped up in Atlanta, Georgia, and Flint, Michigan near the middle of the twentieth century. Soon after, in 1962, a school district in Tucson, Arizona drew on Flint’s model to implement its own program, becoming one of the nation’s most widely-publicized SRO experiments. Within three years, the Minneapolis suburb of Edina had also begun assigning policemen to schools. After Congress passed the Law Enforcement Assistance Act of 1965, Minneapolis and Tucson became the first two American cities to receive federal funding for SRO programs under the Act. Tucson received more than $60,000 per year, and Minneapolis received more than $70,000 per year (roughly half of a million dollars each in today’s dollars).

Called a “living symbol of law and order” by some at the time, the presence of policemen in schools represented a larger, national tide of clarion calls to solder steel fangs onto America’s criminal justice system. Politicians like Minneapolis mayor Charles Stenvig ran for office on a “law and order” platform, with Stenvig even promising to “take the handcuffs off the police.” In the next decade, proposals to install policemen in schools would emerge in other cities like Philadelphia, and in 1978, one reporter counted more than 60 cities in the nation that had adopted SRO programs.

But these programs sparked fiery dissent from the beginning. Some people argued that it should be up to families, social workers, teachers, and counselors—not police officers—to sort out problems at school. Others despised the expansion of police into schools in general, suggesting that it “borders on empire building.” The major legal objection, however, was that police officers might have unlimited discretion in interrogating students who couldn’t have been expected to know the meaning of “due process.” Students, some critics worried, might be coerced into self-incrimination and service as informants on their friends and families.

At the heart of the fight was the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Knowing that the federal grant to Minneapolis’s program was still pending, the director of the ACLU’s Washington office asked the U.S. Department of Justice to require that “under no circumstances would the policeman in the school be able to interrogate any juvenile without the presence of his parent.” He sent a copy of a letter to Lynn Castner, the executive director of the Minnesota ACLU, expressing concerns mostly about student interrogations. The next year, ACLU attorneys in Arizona filed a lawsuit arguing that Tucson’s SRO program was an unconstitutional violation of privacy. The year after that, the Flint ACLU concluded that the Flint program “undermine[s] respect for civil liberties and compromise[s] the integrity of education.”

The ACLU’s early criticism of SROs looked radically different from the kinds of criticism driving policy decisions today. Namely, it avoided drawing attention to policing’s racial dimensions. In doing so, it tried to balance its zealous pushback with the “law and order” mantra that was becoming vogue. In a 1967 op-ed clarifying the Arizona chapter’s position, the local executive director affirmed that “the police have a vital role to play in the preservation of law and order.” He pointed out that the ACLU had even praised policemen in the state “for their professional behavior during the racial disturbances in Phoenix.”

But the unique challenges that policing imposed on people of color weren’t lost on other Americans. “Police don’t listen to us,” lamented one African American teenager in Minneapolis, “they’re always trying to pin something on us.” Two officers had beaten up his brother on his front porch, so not even a gentle SRO would change his mind. “He’s a nice guy … He tries to be different,” the boy explained about one officer, “but to me he can’t. No matter how you put it he’s still a cop.” Wilbur Johnson, an African American man, explained it best in 1966 when he pointed out that SRO programs added “another dimension to an already hostile world” for young minority children. “Police, to the Negro child, represent a threat,” he described, because these children were taught at an early age that “a policeman is sort of Jekyll and Hyde—a wearer of the hood at night and wearer of a tin badge by day.”

Without a sustained acknowledgment of this reality by other opponents of SROs, criticism based on potential erosions of civil liberties soon crumbled. The deliberate ceding of ground to “law and order” advocates meant that evidence of alleged SRO program success would be fatal: If there were more “order” in the end, and if even critics of SROs liked “order,” then how could SROs be a problem? This counter-argument won parents over in Minneapolis. In 1968, the city’s police chief attributed “noticeable decreases in some predelinquent behavior” to the city’s SRO program, and the school board expanded the program to ten more schools.

SRO programs spread in the next decades as part of a larger pattern of police expansion in America’s “War on Poverty,” “War on Drugs,” and “War on Crime.” An allocation of federal funding for school resource officers in the 1990s superpowered the infrastructure of SRO programs, and by 2003 the percentage of schools that had stationed police officers had skyrocketed to more than 30%. The cumulative effect of policies throughout these years, as scholars have documented, was the dramatic expansion of mass incarceration and the disproportionate jailing of African Americans.

The Minneapolis Public School district’s recent decision is a recognition that, even if SROs manage to bring more “law and order” to schools, it is not worth the harm to black and brown children. This makes for a more powerful argument than the original one: it isn’t merely SRO programs’ tactics causing damage, but also the punitive pipeline and culture intrinsic to the SRO concept. The reframing represents a reprioritization of values that guards against the pressure that early critics had felt, a pressure to placate both law-and-order advocates and police-wary Americans. The inescapable reverberation of black death now more clearly demands something beyond skin-deep compromise, even in the face of assertions of program “success.” Yet for all the departures from the past, a reminder from an epoch ago still pulses at the heart of this vision: to countless children of color, the world is already more hostile. It is suffocating and relentless.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary, and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2UaGmnX

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言