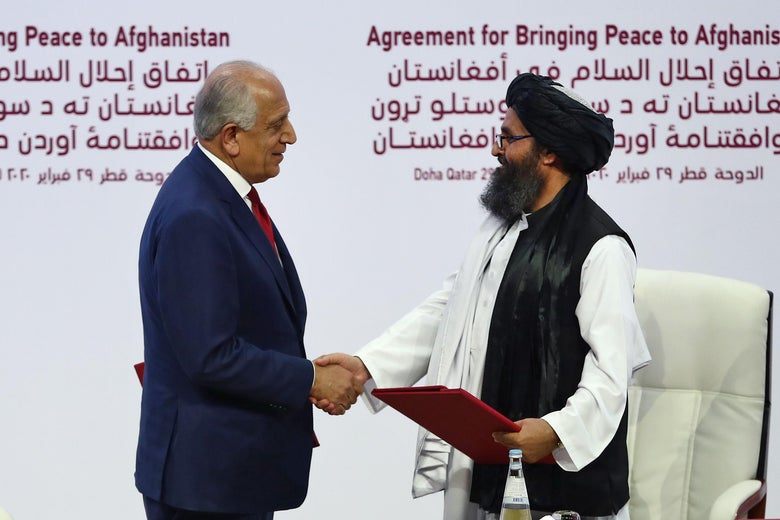

U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar during a ceremony announcing the agreement in Doha, Qatar, on Saturday.

Karim Jaafar/Getty Images

Fighting resumed in Afghanistan on Monday, leading some to note that the peace accord, which the combatants signed on Saturday, may be the shortest on record—a fitting pseudo-coda to the longest war in U.S. history. But in fact, contrary to many media reports, the document in question is not a peace accord, nor does it pretend to be one. It is instead, as the title puts it, an “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan.” (Italics added.)

Nor is it even a cease-fire accord. Yes, the U.S. negotiator, Zalmay Khalilzad, insisted that all sides observe a seven-day “reduction in violence,” beginning on Feb. 21, before signing the document—and they did. But he did not explicitly require that they extend the period of less violence after the signing took place. And so the Taliban announced on Monday that offensive operations would resume, and they did, with a bomb that killed three people and injured 11 at a soccer match in the eastern part of the country.

Then arose another, similarly predictable obstacle. The agreement calls for the release of “up to 5,000” Taliban prisoners—and “up to 1,000” other prisoners (mainly Afghan security forces held by the Taliban)—by March 10, when direct talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban are scheduled to begin. But this prisoner exchange is laid out only in the agreement between the United States and the Taliban. The “Joint Declaration” between the U.S. and the Afghan government—which was published simultaneously—says no such thing. The only mention of prisoners in this document is as follows (again, with italics added):

To create the conditions for reaching a political settlement and achieving a permanent, sustainable ceasefire, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan will participate in a U.S.-facilitated discussion with Taliban representatives on confidence-building measures, to include determining the feasibility of releasing significant numbers of prisoners on both sides.

In other words, the Afghan government agreed to no exchange of prisoners, and its president, Ashraf Ghani, might have good reason to be stunned by such a clause in the U.S. deal with the Taliban. As a result—no surprise—Ghani has said he will not observe the exchange prior to negotiations; he sees the prisoners as vital leverage in those negotiations. If he sticks to his position, which seems rational from his viewpoint, the U.S.–Taliban deal will fall apart.

There are some lessons here for negotiators. In the case of the seven-day “reduction in violence,” they should be very explicit in the language of any treaty signed with the Taliban (or, for that matter, with anyone else): If the Americans expected the period of violence-reduction would be extended beyond the initial seven days, they should have stated so in the document. And they shouldn’t have agreed on a prisoner-exchange without the consent of the Afghan government, which after all is holding the Taliban prisoners.

This allows the United States to get out of Afghanistan, which is what Trump has wanted all along.

If the three sides of this awkward arrangement can get past the initial phase of the “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan,” the next steps are quite ambitious. Within 135 days, the United States will cut its number of troops to 8,500—about the same number that President Obama left in place, before President Trump doubled the deployment—and the NATO allies will reduce their numbers proportionately. Then, by May 2021, the U.S. and its allies will withdraw all remaining armed forces, as well as “all non-diplomatic civilian personnel, private security contractors, trainers, advisers, and support service personnel.”

In exchange, the Taliban agree not to let any of its members “use the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies.” And they also agree to bar members from having any association with—or providing visas, passports, or other assistance to—any groups or individuals that do pose a threat.

At that point, the United States will pursue good relations with a more inclusive Afghan government, to be determined by the Afghans themselves, including a review of relaxing sanctions against Taliban members who are part of the new regime.

In other words, if this deal goes through, the United States and NATO will be out of Afghanistan entirely, except for a routine diplomatic presence. The war—at least our part in it—will be over.

That being the case, it’s not clear how the Taliban’s side of the deal will be enforced, or who will enforce it. In a speech on Feb. 29, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper referred to the agreement—which was released on the same day—as “conditions-based,” requiring “the Taliban to maintain the ongoing reduction in violence” and noting, “If the Taliban fail to uphold their commitments, they will forfeit their chance to engage in negotiations with the Afghan government and will not have a say in the future of this country.”

The problem is, the agreement nowhere states that the United States will pull out of its commitments if the Taliban pull out of theirs.

Really, this is a deal allowing the United States to get out of Afghanistan. This is what President Donald Trump has wanted all along. Early in his term, then–Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis and then–National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster convinced Trump to give war another chance, arguing that their “new strategy” could produce “victory.” But the strategy wasn’t new; the terms of victory weren’t defined. And now, with a more pliant team of advisers, Trump is getting his way—and not without reason.

The original purpose of this war—ousting the Taliban from power, killing or capturing Osama bin Laden, decimating al-Qaida—has long been accomplished. The more ambitious purpose—to help Afghanistan’s leaders build a democracy—was always chimerical. The top U.S. commanders always said the war couldn’t be won, as long as the local government was corrupt. Yet at the same time, they opposed peace talks until the U.S. troops attained a military advantage that could be used as leverage in the negotiations. Meanwhile, the Taliban are Afghans; their chief demand has always been the withdrawal of all foreign troops, very much including American troops. Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. negotiator, who was born in Afghanistan and speaks fluent Pashtun, has done the best he could. It may not be good enough to keep the Taliban from dominating the country again. But nothing was ever likely to be good enough to do that. And so it’s time to leave. The “Agreement to Bring Peace to Afghanistan” is only the beginning of that process. It may also be, in part, an illusion. But better to succumb to this illusion than one that keeps us fighting there another 20 years.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/32IofJ7

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言