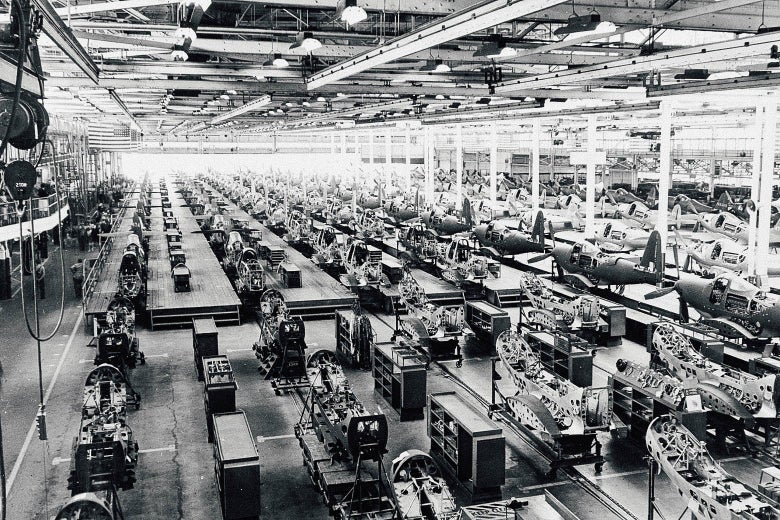

The assembly plant of the Bell Aircraft Corp. at Wheatfield, New York, near Niagara Falls, in the 1940s.

Library of Congress

With America’s belated realization that it will require a full-scale mobilization to take on the COVID-19 pandemic, both the government and the public have turned to the nation’s largest tech companies to be a part of the solution. So Future Tense editorial director Andrés Martinez invited three writers who’ve authored books on the relationship between government and the private sector in past times of crisis (WWII, the Cold War, the environmental time bomb of climate change) to address the present moment, and how it might affect the relationship between “Big Tech,” the government, and the public.

Andrés Martinez: Good morning, Margaret, Steve, and Jamie, and thanks for taking some time to Slack with Future Tense. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we see President Donald Trump seeking (on some days, at least) to evoke our shared narratives of past mobilizations in times of crisis, by proclaiming himself a “wartime president.” Do you think there is an analogous mindset switch in what we might call “Big Tech”? Margaret, let’s start with you since you have spent so much time thinking and writing about Silicon Valley’s DNA. Do our Big Tech players now think of themselves as “wartime companies” pressed into service?

Margaret O’Mara: Hi all, and thanks for having me. What strange times these all are, including for Big Tech companies. In many ways COVID-19 is an accelerant poured onto already evolving change—of the very largest companies and their CEOs becoming public, even political, figures, weighing in on major crises and societal challenges. There’s Bill Gates and his foundation, of course. But Jeff Bezos on climate change, Mark Zuckerberg and public health et al., and more. In the absence of organized federal leadership in the U.S., the critical role that companies like Amazon are playing (supply chain) and Facebook (communication and news) becomes even more pronounced.

A big contrast from, say, the 1930s and 1940s, when FDR’s government called large companies into service through large-scale mobilization, is that the Trump administration has, to date, hesitated to mandate corporate action (including from tech). Trump is far more like Herbert Hoover than Franklin Roosevelt in that regard. And we know how that turned out!

Martinez: It’s interesting to call this an accelerant to ongoing change. Most of us seem to oscillate between resenting and being awestruck at the reach and power of our tech giants, but in this crisis I also see a lot of us wanting to rely on their reach and power to provide solutions that we might feel are beyond the government’s competence. Steve, how do you see this balancing out? Are we going to emerge from this crisis with Big Tech proclaimed as our savior? (I assume Google will build that website!)

Steve LeVine: Thanks, Andrés, and like Margaret, thrilled to be in this group. I am struck not by how COVID-19 is an accelerant to certain trends (though it is; for instance in the decoupling from China) but how it puts Big Tech into position to totally reverse its public image. Amazon has shifted from villain to be broken apart to the central actor in the U.S. economy, apart from the Fed itself; it shifts from demon to a public good. That is astonishing whiplash. There is a question as to whether this carries with time, and especially when the crisis is over. That’s up to their actions and their PR departments.

I do think Americans are desperately hungry for national leadership and are not getting it—someone who takes charge and says, Right, we are all going on lockdown for two weeks and we are going to beat this thing. Fear not. Trump is failing in that respect, and no single company can be expected to take that role. But perhaps an all–of–Silicon Valley approach?

O’Mara: I agree with Steve: The pendulum swing from burn-it-all-down to tech-as-essential-service has been swift! Yet the techlash of the past few years has dimmed public faith in tech CEOs being the ones to save us (which was a very strong faith, for some time!).

Martinez: Obviously when we think about developing vaccines, there is another set of players in the private sector that will play a crucial role in this saga, but it is striking how the biggest tech companies we are talking about—the Googles, Amazons, and Facebooks—are not only looked upon to help with our collective response to the problem, but also to help us carry on with our daily lives. The present circumstances should help them consolidate their dominance.

Jamie, your forthcoming book looks at the nerdy “band of brothers’ within the newly created Office of Scientific Research and Development who developed the (surprisingly underappreciated) first “smart weapon,” the proximity fuse that helped save London from Hitler’s V-1 rockets late in World War II. More broadly, even before the U.S. entered the conflict, Roosevelt asked the president of GM, William Knudsen, to leave what was then the world’s largest industrial company to oversee the mobilization of the U.S. economy to “outbuild Hitler,” as Knudsen put it. Do you see echoes of those times in the way we turn to the private sector nowadays, or has the world just changed too much?

“Tech companies have had a kind of collective amnesia about the big-government drivers of their development.” — Margaret O’Mara

Jamie Holmes: The main parallel that interests me is one we’ve touched on: To what degree will this be a federal response? There were two great mobilizations, as you mention, Andrés. One was in industrial production of airplanes, ships, jeeps, weapons; the second was in mobilizing scientific brainpower to the war effort through the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Out of that latter effort came the atom bomb, advances in radar, penicillin, and blood substitutes. There was also a lot of work done on vaccines through OSRD’s Committee on Medical Research, including vaccines for flu and pneumonia. Both of these mobilizations required strong federal control, the first through the War Production Board and the second through OSRD. We’re seeing now the consequences of what happens without a coordinated federal response.

Martinez: Ah yes, thank goodness for penicillin.

O’Mara: And out of OSRD comes the great Cold War push in electronics, including microelectronics and communication devices, which was the foundation for the tech industry we have today! It all comes full circle.

Martinez: I keep talking about “private sector,” but a voice in my head (Margaret’s book) is reminding me that below the hood of the flashy sports car that is Silicon Valley lies a big government engine, and Steve, your book looked at the catalyst role often played by our national labs, too. Is everything in the end a public-private partnership? (I always think of toll roads when I hear that phrase.)

O’Mara: Yes, especially in the U.S. context. We often think of public and private as two realms. They are interconnected and interdependent and have been throughout American history.

LeVine: The biggest things have happened when the government points the direction and puts a lot of money behind it. Tesla—Elon Musk’s whole enterprise—thrives in that context.

O’Mara: Yes. Tech companies, especially, have had a kind of collective amnesia about the big-government drivers of their development, and Steve’s example of Tesla is an excellent one. There are things only governments can do, and basic research—blue-sky research, for things without immediate commercial application or near-term profitability—is one of them. Health and medical research and large-scale public health mobilization is part of that.

LeVine: Yep, Tesla got $465 million in 2010 from the stimulus bill (which was paid back early with interest).

Martinez: In addition to peer-pressuring Google into building a website, the administration has apparently been asking automakers and others to build respirators, and masks. Do you all believe the government should act more coercively in this regard and assume more of a controlling role?

LeVine: Yes.

O’Mara: I agree. It also can be a combination of carrots and sticks. If we look at WWII, and Jamie, you may have more to say on this, you see the Roosevelt administration both imposing pretty restrictive things like wage and price controls, and forcing assembly lines to switch from passenger cars to tanks, but you also saw lots of incentives for corporations to come on board—tax breaks, etc. And keep in mind that wartime was good for business—big contractors made plenty of money during both world wars. (Daddy Warbucks was real!)

Holmes: Yes. And even with OSRD, Vannevar Bush set up the partnerships with industrial research labs as contracts, not grants. That was important to him. He didn’t see them as paternalistic relationships.

Martinez: Our tech companies are now global enterprises, but pandemics have a way of rolling back globalization. Steve mentioned a decoupling with China, and we’re also seeing plenty of finger-pointing and disrupted supply chains.

“National security depends on empowering scientists.” — Jamie Holmes

LeVine: This is a very good point, Andrés. Big Tech can do well by itself by producing answers not just in the U.S., but in Europe and elsewhere as well.

O’Mara: Big Tech is particularly well-positioned to remind us that certain things transcend nationalism. COVID-19 is a global challenge, a war with a common enemy, and the global reach and workforce of America’s biggest tech companies creates an imperative for them to provide moral leadership and a global perspective. That was another critical thing that the U.S. government did in the 1940s, fostering internationalism and the growth of supranational institutions for wartime and postwar reconstruction and rehabilitation.

Martinez: Like WHO?

O’Mara: Yes, the World Health Organization, created in context of U.N. in late 1940s. A truly multinational effort but with the U.S. as the lead.

LeVine: Companies are definitely stepping over themselves to appear to be acting in the public good, as well as to protect their employees. But I don’t see that many collaborative signs, though. Anyone else see that at this moment?

O’Mara: I don’t see collaborative signs—yet. But tech companies have global supply chains and customer bases that give them better visibility into how interconnected we all are. I’d like to see their leaders really emphasizing that interconnectedness publicly. Mobilizing and coordinating with the U.S. government and being global citizens do not have to be two different or contradictory things.

LeVine: It’s especially important because scapegoating and attacking the “other” is a feature of pandemics. It happened in the plague and the great influenza.

Martinez: I am struck by how we haven’t seen shots of our president talking to foreign leaders about this. In other times …

“Should Trump appoint a CoronaCzar from outside government?” — Andrés Martinez

O’Mara: I know. I’d love a little more Roosevelt and Churchill these days.

What I’m also seeing is tech companies playing the same kind of catch-up that they have since the 2016 election, when both the presidential race in the U.S. and Brexit, among other global political developments, showed how disruptive and influential social media platforms could be. Silicon Valley’s willful diffidence about (and antipathy toward) politics and government has been a weakness there.

LeVine: Agreed. This is a time for the tech companies to transcend 2016, the Brandeis-branded antitrust fever and so on, and show they can be a public good.

Holmes: It’s interesting how we are coming back to wartime analogies, which are useful but only up to a point. They’re useful in terms of encouraging people to take the crisis seriously, and in encouraging solidarity. Certainly the crisis has revealed, as World War II did, that national security depends on empowering scientists. And there are strong parallels and lessons to be learned in how we mobilized industry and science. Then again, strangely enough, physical courage against the coronavirus (i.e., going out and carrying on) isn’t patriotic, it’s treasonous.

I also wonder about some of the lasting legacies we might be in for as we rely on Big Tech in our hour of need. Consider the privacy concerns raised by a pervasive reliance on GPS technologies and our phones to enforce contact-tracing and quarantines as we move eventually toward a return to some semblance of normalcy and “turn the faucet back on.” I wonder how our relationship to to invasive tracking tools changes if they turn out to be one of the big heroes of this struggle.

LeVine: Yuval Harari had a substantial piece in last weekend’s Financial Times in which he posited a scary scenario of all of us being not only under visual surveillance, but of having our blood pressure and temperature tracked. For health purposes, of course, except in a place like North Korea, they’d know whether, watching the great leader, your blood is boiling and, as Harari put it, then “you’re through.”

“The economy won’t get fixed until the virus is either killed or we seem to be getting there.” — Steve LeVine

O’Mara: This really ratchets up America’s tortured and contradictory relationship with privacy to the next level. We fret about Facebook tracking us and Ring doorbells and Alexa watching us, but yet we keep on using and buying them. And now, irony of ironies, those devices may be the ones that help curb the devastation of this pandemic.

Martinez: One final question: Should Trump appoint a CoronaCzar from outside government (akin to Knudsen in WWII) to oversee the overall effort? And if so, who would you nominate for the gig?

O’Mara: First, CoronaCzar is quite a title. Second, yes, and my nominee is Brad Smith of Microsoft.

LeVine: Yes, and I nominate Bill Gates, because he is widely respected and not busy running a real company. It’s actually crazy that he hasn’t already been tapped. It would be smart politically and really the economy won’t get fixed until the virus is either killed or we seem to be getting there.

O’Mara: I will second BG. How strange to think that Microsoft is now the grown-up in the room. Who would have thought that we’d be suggesting Bill Gates for this kind of thing 20, 30 years ago?

Interestingly I’d say one catalyst in transforming how we think of Microsoft was the antitrust enforcement two decades ago. Microsoft didn’t have to break up, nor was the DOJ case necessary to make Google possible (as some argue), but the experience both instilled a certain degree of caution within the company and made it more appreciative of the importance of working with government. And so leaders like Microsoft president Brad Smith (whose own book last year was very good) spend a great deal of time working constructively with governments around the world on a range of tech policy issues and have a really measured and smart understanding of the stakes and opportunities.

Holmes: I’m not so concerned whether the coordination comes from inside government or not. But right now we’ve been told that the vice president is running the show, and that FEMA is in charge, and that Health and Human Services is in charge. So many of the problems we’re having can be traced to a lack of centralized leadership. It’s absurd that we have governors fighting with one another to save lives. Foreign businesses are literally donating directly to states. But if I have to pick one person to appoint, I’ll agree with Steve and Margaret.

Martinez: Bring on Bill Gates to solve our problems! You guys just want to give Bernie another heart attack. It makes a lot of sense but also feels like throwing in the towel and succumbing to Big Tech once and for all.

Time flies when you are having fun, and we’re up on the hour, so I will let you all go. Thanks so much, and I look forward to the Gates coronation press conference this afternoon.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2QQEVt2

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言