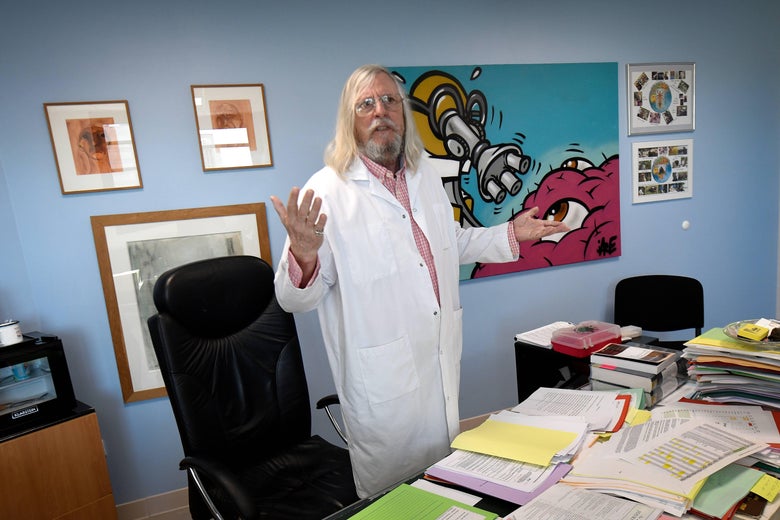

A picture taken on February 26, 2020 shows French professor Didier Raoult, biologist and professor of microbiology, specialized in infectious diseases and director of IHU Mediterranee Infection Institute posing in his office in Marseille, southeastern France.

GERARD JULIEN/Getty Images

President Donald Trump’s daily press briefing on the coronavirus pandemic has been compared to many things: state propaganda, daily talk show, three-ring circus. It is somehow all of these things, but it is also something else: an infomercial. For the past two weeks, the president has been hawking a miracle cure: the anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine. He has hailed it as “very encouraging,” a “phenomenal drug,” and “the biggest game changer in the history of medicine.” Trump has also portrayed it as a Hail Mary: “What do we have to lose? I feel very good about it.”

It is no longer news that the scientist placed behind Trump during the briefings, Dr. Anthony Fauci, feels less good about the drug. Nor is it news that other American researchers worry we have much to lose if testing protocols are ignored. Lives, for example, can be lost. An Arizona resident died on March 23 after self-medicating himself with chloroquine phosphate—a related compound chemical typically used to clean aquariums—while doctors who prescribe hydroxychloroquine for patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis are finding that the drug is being hoarded.

Trump may not be aware that the hydroxycholoquine hype is French in origin. The researcher responsible for the “molécule miracle” is Didier Raoult. The founder and director of Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) in Marseilles, the 68-year old Raoult has compiled a sometimes dazzling, sometimes disturbing career that could have been scripted by Marcel Pagnol or Honoré de Balzac. Born in Senegal Raoult defied his father, who was serving there as a military doctor, and quit high school in his junior year. Signing up with the French merchant marine, the young Raoult spent the next two years at sea.

Returning to France, he graduated from medical school and nimbly made his way in both the political and professional worlds. Not only did he become an internationally recognized researcher, but he also a nationally recognized power-player. Cultivating politicians as carefully as he cultivated petri dishes, Raoult overcame the opposition of older research institutions and, with the support of then-President Nicolas Sarkozy, created the IHU ten years ago. Despite the doubts, Raoult’s work on infectious disease earned him a place on the French government’s Covid-19 commission.

Not surprisingly, Raoult’s rapid rise raised as many eyebrows as huzzahs. While his fans applaud the 3,000 scientific articles Raoult has cosigned, his critics argue that these staggering numbers do not add up. Do the math, they remark, and it turns out the Marseillaise researcher publishes more papers in a month then most productive researchers publish in a career. Raoult’s method, according to one critic, is to task a young researcher at IHU with an experiment, then cosign the piece before it is submitted to publication. “Raoult is thus able to reach this absolutely insane number of publications every year,” according to one anonymous source quoted by the site Mediapart. More disturbingly, the critic added, “it is simply impossible for Raoult to verify all of these papers.”

Indeed, the question of verification hovers over Raoult’s clinical trial on the effects of hydroxychloroquine on the novel coronavirus. Combining a regimen of Plaquenil—the commercial name of hydroxychloroquine—and an antibiotic, Raoult treated 24 patients at IHU in early March who had tested positive for Covid-19. After six days, the virus had vacated the bodies of three quarters of those same patients. On March 16, Raoult announced the results not in a scientific journal but in a YouTube video, in which he declared the jig was up for the virus. Predictably, his self-proclaimed victory then ignited the hysteria that has since swept the world and reached as far as the Oval Office.

In France, pharmacies have been overwhelmed by demands for Plaquenil, leading one pharmacist quoted by Le Monde to exclaim: “Perhaps Raoult is right, but instead of taking the time to carry out a serious study, he has given us two months of theatrics.”

Critics argue that not only were there too few subjects in the chloroquine study, but that some of them dropped out during the trial, potentially skewing the results. In addition, Raoult has not released the raw data from the trial which, remarkably, was not double-blinded. According to Dominique Costagliola, chief epidemiologist at the Pasteur Institute, the trial was so slapdash that “it is impossible to interpret the described result as being attributable to the hydroxychloroquine treatment.”

If this sounds depressingly familiar, it should. There are several disquieting parallels between the stable genius who claims to “understand that whole scientific world” and the reputed genius who claims to have defeated Covid-19. Like Trump, Raoult has made himself a brand: the outsider who defies a sclerotic and corrupt establishment. Like Trump, Raoult is not just a climate skeptic—in 2103, he declared that climate predictions are “absurd,” but a pandemic skeptic. “Three people in China die from a virus and that sparks a global alert,” he observed in an IHU video. “This is crazy.” The video was posted on January 21, just one day before Trump reassured Americans that he has the virus “totally under control.”

Raoult has cast his critics as creatures of a kind of état profond, one peopled by “pedantic Parisian doctors” incapable of doing real research. In effect, he has told the world that he alone can fix it. On Sunday, the FDA issued an emergency authorization to add the drug to the Strategic National Stockpile, permitting doctors to use it in cases they deem critical. Yet the clinical trials must still run their proper course. For now, Raoult has given unproven hope to millions, uncharted dangers for those afflicted by lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and unavoidable despair for those who listen to the U.S. president’s daily press briefings.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2QQPNY3

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言