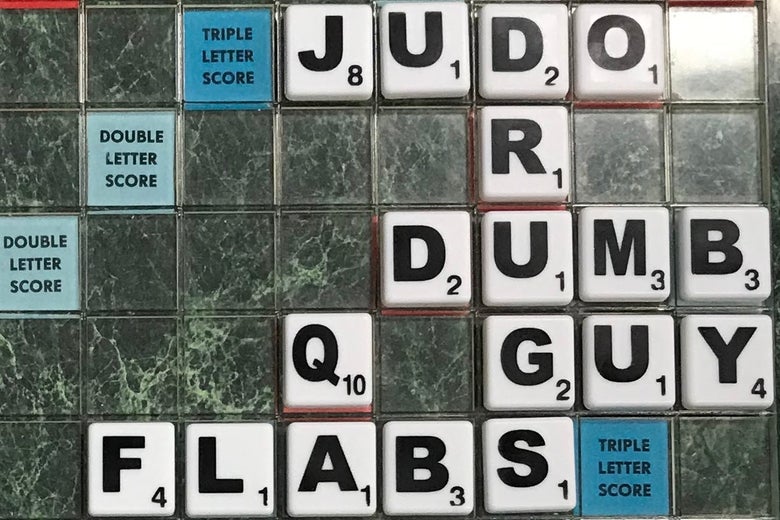

A board from the author’s Scrabble tournament in Charlottesville, Va.

Stefan Fatsis

Last weekend, my teenage daughter and I played in a Scrabble tournament. I finished third out of 18 players with a 10–6 record, won $300, and made some cool plays: QUINOAS for 102 points to open a game and HONOURS for 91 to close one; FANZINES, APNOEAS, BEANERY, EENSIER. She went 9–7 and took home $75. The players paused to remember a legendary champion who died recently. We swapped stories and analyzed our games. My daughter and I had fun. We also ate tapas in a crowded restaurant, and repeatedly stuck our hands into fabric bags filled with plastic Scrabble tiles, bags into which our opponents also stuck their hands over and over.

Before the tournament, I reminded players to wash their tiles and bags. (They’re an obvious germ vector, and also get really stinky.) There was hand sanitizer on the playing tables. My skin was so dry from spritzing and washing that my knuckles bled. But now—with “social distancing” and “self-quarantine” making early runs for 2020 Word of the Year—I’m questioning the wisdom, and ethics, of my decision to play.

When I drew my first tiles of the tournament—ADEEHIR; alas, HEADIER didn’t play, nor did the only possible eight-letter word, DEHAIRED—nobody in American society hadn’t started hanging CLOSED signs, particularly sports society. A week later, professional and college basketball are gone. So are baseball, soccer, hockey, football, golf, tennis, rugby, road races, car races, and chess and esports tournaments.

But the little world of competitive Scrabble is playing on, its official governing body declining to suspend play. The debate among players over whether games should continue is representative of the debates being waged in other corners of America that haven’t gone dark. People are still grabbing subway poles and flying in airplanes, believing Rush Limbaugh and Fox News. What are the risks of doing what you love doing? Who gets to decide when you have to stop?

Scrabble is owned by Hasbro Inc., but the toymaker has almost no involvement in the competitive game. The 2,200 active players, 150 or so clubs, and 400 or so tournaments a year are regulated by the North American Scrabble Players Association, which is funded by player dues and tournament participation fees. Hasbro grants NASPA a license to use the word “Scrabble” in its name and promotional efforts.

NASPA hasn’t ignored the coronavirus crisis. Its website includes a detailed COVID-19 wiki. The guidelines are all sensible, some are obvious, and a few very specific: Don’t play if you’ve tested positive, wash your hands, disinfect your equipment, use a smartphone app instead of a communal laptop to adjudicate word challenges. “If you have to sneeze or cough, and are not wearing a face mask, do so into a tissue or your elbow and away from all playing equipment and players,” the guidelines advise. “Then pause the [game timer] and call the director to discuss whether you should withdraw from the event.”

The wiki warns that it’s easy to “communicate respiratory diseases” while playing Scrabble—proximity, confined spaces, shared equipment, travel—and players should “carefully assess their health risk” and “follow best practices” to avoid contracting the coronavirus. But the decision to stage club sessions and tournaments remains, at least for now, with the people who direct and play in them. Unlike the National Basketball Association or Major League Baseball, NASPA has refused to suspend play.

Clubs in Orlando, Seattle, and New Jersey have gone on hiatus anyway, and tournaments this weekend in Nashville and Poughkeepsie, N.Y., were canceled. But three events were on; one director offered disposable gloves to attendees. “We are down to a dozen players now, from 30-odd a week ago and 46 last year,” the director of a tournament in Medina, Ohio, wrote on NASPA’s Facebook page on Friday morning. “I’m not quite sure what will happen with the four pounds of Malley’s chocolates I bought last week, or the 8 boxes of Girl Scout cookies I ordered for the event. Oh well, if all of the pasta is sold out in the area, at least I’ll have something to survive on!” The number of participants dropped again before the event began: On Saturday, it was down to eight players.

Online, Scrabblers debated community behavior and individual responsibility. One called for NASPA to order a halt to all club meetings and tournaments. Another disagreed. “If ppl wanna show up, they can show up. If they don’t, they don’t have to. Simple,” he wrote. A medical doctor said it wasn’t. “It is not about individual fear,” she wrote. “It is about public health measures that will protect communities and slow the epidemic so that available resources are not overwhelmed.”

Players quibbled over Centers for Disease Control advisories and whether to trust a Vanderbilt University infectious disease expert who, in a news story, advised people over 60 or with underlying health issues to avoid crowds and routine public events. (A lot of Scrabble players are over 60.) “No one should ever blindly believe what a random doctor says,” one player commented. “I think we are all smart enough here to decide what is right for each person’s self.”

That ticked off Mina Le, an expert-level player and an ear, nose, and throat surgeon at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. Le organized a petition asking NASPA to shut things down, which she said could help slow transmission and “flatten the curve” of the illness. “You would be saving lives not only among your members but among their families, friends, coworkers, and acquaintances,” Le wrote in the petition. “Imagine any of those people dying because of a board game.” The petition was signed by 22 players, including seven more physicians, a nurse, a radiology professor, and, full disclosure, me.

I talked to Le on Friday. A month ago, she said, she was skeptical about the potential risk in the United States. But her opinion evolved as the virus spread. Ditching Scrabble was a small concession to the greater good, she said. “It’s more contagious than Broadway and Disneyland and all these other places that have already closed,” Le said of the game. “There’s no adverse economic impact to shutting down Scrabble tournaments. It’s a completely nonessential activity. That’s what I don’t understand about the resistance.”

NASPA chief executive John Chew wrote the coronavirus wiki and, as co-chair of the organization’s advisory board, would rule on Le’s petition. On the NASPA Facebook page, Chew, who studied mathematics, posted a link to an article about the low odds of dying from COVID-19 or inadvertently causing someone else’s death by transmitting the virus. He said the risk of one death from the coronavirus in Ontario, where he lives, could be measured in “micromorts.”

I’ve known Chew since I started playing and writing about Scrabble two decades ago. We’re friends. I asked him about sidelining clubs and tournaments. The decision should be local, he said. “I do not know if the situation is different in the United States,” Chew emailed, “but here in Canada we are used to following directions from public health authorities concerning pandemic health issues, and not seeking guidance from private organizations and individuals with less specialist expertise.”

“To argue reductio ad absurdum,” he said, “it would not make sense say for the [World Health Organization] to mandate (if it had the power to do so) the same restrictions globally, from Wuhan to Fiji,” Chew wrote. “Likewise, it does not make sense for NASPA to tell directors what they should be doing locally, other than to do what local government officials are telling them to do.”

But NASPA is akin to the NBA or MLB, I replied, overseeing a coast-to-coast sport. NASPA itself operates just one tournament a year, a championship that attracts more than 400 players, scheduled for early August in Baltimore. But it establishes rules for every other player-run tournament. So while directors and players can monitor municipal guidance and make individual choices, they can also make uninformed or irresponsible decisions. Dozens of governmental and public-health officials have recommended “social distancing.” Didn’t that qualify as guidance for Scrabble tournaments? Didn’t NASPA have a responsibility, regardless of the numerical odds of contamination, to stop the flow of tiles?

His response:

It’s like weather. There might be a major blizzard in Boston, or a hurricane in Florida. We expect our directors to behave responsibly and take whatever measures are locally appropriate. We do not monitor weather forecasts and provide guidance to directors about weather emergencies, because we do not have the resources or expertise to do so, and because it would be duplicating official efforts. And then what if we get something wrong? At best directors might receive conflicting advice; at worst they might make the wrong decision based on bad information.

There is no circumstance in which pausing Scrabble during a pandemic is the wrong decision. The math may say it’s not necessary. The body and brain don’t care about the math. (A splinter Scrabble organization, the Word Game Players’ Organization, has suspended all tournaments until at least April 30.) I’m not symptomatic, and I hope no one from the Charlottesville tournament is, either. But I’m grappling with whether I needlessly put myself, my kid, and others at risk.

Scrabble is a huge part of my life and my identity. I love the challenge of every rack, the beauty of the words, the rush of competition—one on one, across the board from another human being. But I won’t be playing outside of my living room for a while. I’m cleaning my tiles again. Others are making the same choice; players have begun organizing online tournaments.

During the week, I watched with empathy as the director of that tournament in Ohio wrestled in real time with what to do. “Yes, in theory, I could cancel,” he wrote on Facebook. “However, I promised several people … that I would run the tourney, and so I shall do so.” Another player replied, “Just keep them all spread out. Godspeed.”

Listen to an episode of Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen below, or subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Play, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2ILhCwp

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言