Capitol Hill Books

The first thing I did after I put on the gloves was I closed my eyes and breathed in. A smell so familiar it might as well be my own body: the brittle must of books, the dust and ink and decades-old fingerprints on a hundred thousand volumes. You might know that smell too, might be able to call it to mind right now. The smell of your university library, of the shelves at your grandparents’ house, of every used bookshop you’ve ever browsed. The smell of the last bookstore I’ll visit, I know, for quite some time.

A few days ago I saw a message on Twitter from a bookstore I like in Washington, D.C., inviting patrons to book individual one-hour shopping appointments. “Ever dream of having Capitol Hill Books all to yourself?” the tweet read. “Now you can.” I had, in fact, often dreamed of having a used bookshop all to myself, though my dreams mostly involved me living above the store, which I owned, because I somehow had become a rich dilettante. But I would settle for this one-hour quarantine version. Like everyone I knew, I was already feeling stir-crazy, missing not only human interaction but the mere experience of being in a place that wasn’t my home or the three-block radius around it. I reserved a slot Friday morning at 10.

The drive was ghostly, my familiar route governed by the old rush-hour tolls and rules but as empty of cars as if I was driving at midnight. I parked about 15 minutes early and walked around the block, bending big six-foot arcs around the dogwalkers, letting the joggers bend big six-foot arcs around me. The moment my phone read 10:00 I knocked on the door of the shop, with its now-moot hours of operation and its CLOSED sign. The man who answered had kind eyes, salt-and-pepper hair, a short beard. “Hi, Dan,” he said. His name was Kyle. We didn’t shake hands. He offered hand sanitizer and laid a pair of gloves on the counter. “I’ll be here,” he said as I snapped the gloves on, indicating the front desk. “The shop is yours.”

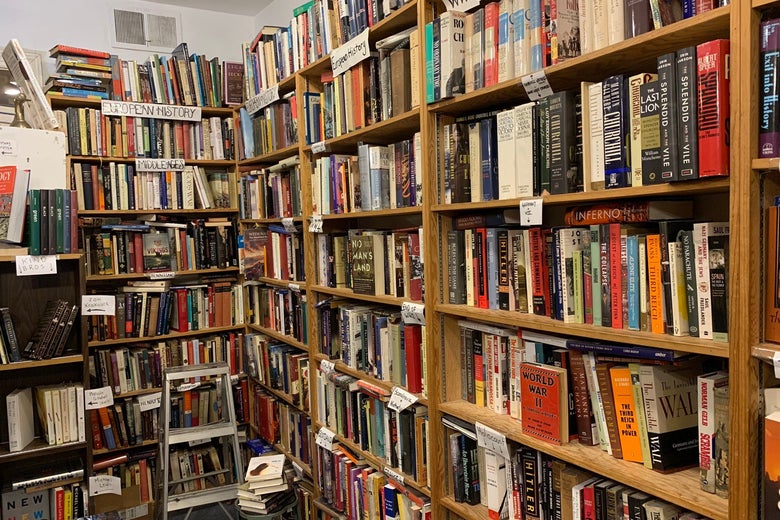

I started on the first floor: history, mostly. When I found a book I wanted to buy, I merrily tossed it to the floor; the store was mine, after all, and I didn’t need to carry my growing pile along with me today. I ran my glove-clad finger across spines like a stick across a fence, stopping at each title that seemed even a little bit interesting.

For every person who loves shopping in used bookstores, the moment your finger stops is the moment a decision tree flowers before you. Do you pull the book out a little, to see its cover? Do you pull the book off the shelf, to read its jacket copy?

Do you want to read this? (The answer, in the bookshop, is almost always yes.)

Will you actually read it? If the answer is yes, as it is perhaps a quarter of the time, you add the book to your pile.

If the answer is no, though, often you don’t immediately put the book back. You pause, you hold the book before your face, and you ask yourself one more question: Might you, one day, become the kind of person who would actually read this book? Should you buy the book just in case? I find that about half the time my answer to that question is yes.

Buying a book means making an investment in your own future, a kind of bet. It’s an expression of optimism about what your life will look like next week or next month, what person you will be five years from now. Freed by Capitol Hill Books for one short hour after weeks of anxiety about the future, I was hungry to imagine times to come in which I could read books about Victorian marriages or medieval trial by combat. After weeks of being the worst, laziest, most stuck-to-the-internet version of myself, I found myself desperate to imagine a version of myself who could settle into a chair, put away my phone, and read this gorgeous paperback of Thomas Merton’s No Man Is an Island. So all three of those books, and others, landed on the growing pile in the middle of the floor.

The ones that still don’t make the cut? You put them back, with sorrow, knowing that someday you will think back on at least one of those books and regret not buying it. Often the tightly-packed shelf no longer can comfortably accommodate the book that occupied that space just moments ago, and you lay the book horizontally atop its shelved companions, the resting position of the book that almost made it but faltered at the finish, an invitation to the next browser, if there is a next browser, to look more carefully.

I pulled a book about the Paris Commune out of Middle Ages, paged through it, and helpfully reshelved it in the section marked the Victorian Era.

Buying a book means making an investment in your own future, a kind of bet.

It was 10:20. I ducked my head as I trundled downstairs into the sci-fi section. I made my habitual check for anything by John M. Ford; as always, there was nothing. I picked up a fun-looking novel by a writer I’ve never read before. I picked up the first volume of Scott Pilgrim to replace the one my children lost. Downstairs is where the store mixes genre with academia, journalism with crappy golf books. It’s where the humor section lives, that mishmash of classic comics and Tim Allen books. Every book and quasi-book ever published has a chance at landing in a used bookstore, and a good shop collects the whole of the world of words for you: The erudite, the junk, the pulp, the pop, the exhaustive, the delightful, the ambitious, the embarrassing. Books by writers once beloved, writers lost before you had a chance to discover them, writers who deserved more of a shot.

It’s in used bookstores that you see that just about everyone reads something. Here in Capitol Hill Books I discovered that in 1976 a woman named Beverly in Annapolis, Maryland was given a Farley Mowat book by someone who loved her. In a used bookstore in the Milwaukee airport, I once found a paperback novelization of the 1990 Christian Slater movie Pump Up the Volume with sentence after sentence underlined by someone’s attentive pen. In a bookshop in Savannah, I found a first edition of Harry Crews’ Body given to Dick Smothers by his friend “Lela” for Christmas 1990, and inscribed by Smothers to another friend, “Jody,” the following November. (Comedy legend Smothers loved the novel.)

It’s in used bookstores that you might find the book that will change your life. In fact, you probably will.

On the second floor, in the Mystery room, a radio played NPR, where commentators discussed the debate in Congress over a coronavirus relief bill, updated the number of Americans sick, the number dead. I pulled a mid-period Stephen King for my daughter and retreated to the back, to the store’s enormous fiction collection. I had 15 minutes left. My neck was sore from tilting my head just to the right for so long. I plucked two Alice Adams books and a 1989 Soho Press novel I’d never heard of by someone named Edward Allen. As I do in every store, I looked for Evan Connell’s Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge. I own one, but can never remember which one it is. (Writing this essay, I just checked—it’s Mr. Bridge. Soon, I know, I will be the kind of person who reads it.)

And just before my time was up I saw something I’d never seen before, something I’d dreamed of for years: my own book, tucked into the Music section. Lying horizontally atop other books, in fact, the leavings of some previous customer who made it most of the way down the decision tree before deciding—with, I’m certain, deep regret—not to buy it. I touched it gently and smiled: a year of my life, nestled among all these years of all these other writers’ lives.

Dan Kois

Kyle called up the stairs. “Our next group is coming. You’ll need to check out.” I picked up my selections off the floor and glumly walked down the stairs, leaving my book and all its compatriots behind. In just a few days, Washington would close all non-essential businesses, and Capitol Hill Books would suspend its one-hour reservations, only fulfilling orders by email. You should drop them, or your favorite used bookstore, a line.

At the register I noticed one last volume on the store’s small new books table, the first in N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, which I’ve still not read. “And this,” I said, adding it to the pile even as Kyle, clad in his own gloves, rang the books up.

“If you had eight hours, would you still be grabbing books at the end?” Kyle asked after he told me my total, which I will not reveal here.

“Yes,” I groaned.

There was another knock at the door. My hour lost in this space felt like forever but also like no time at all. What a gift, this hour to be elsewhere, neverwhere, the Other World, in the place beyond the wardrobe. I tried not to cry as I stacked the books into two totes. Outside, the air was warm and the street was empty. I heard the bookshop’s door shut behind me. I looked down at my hands, holding my bags full of books. I was still wearing the gloves.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3dvvtVP

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言