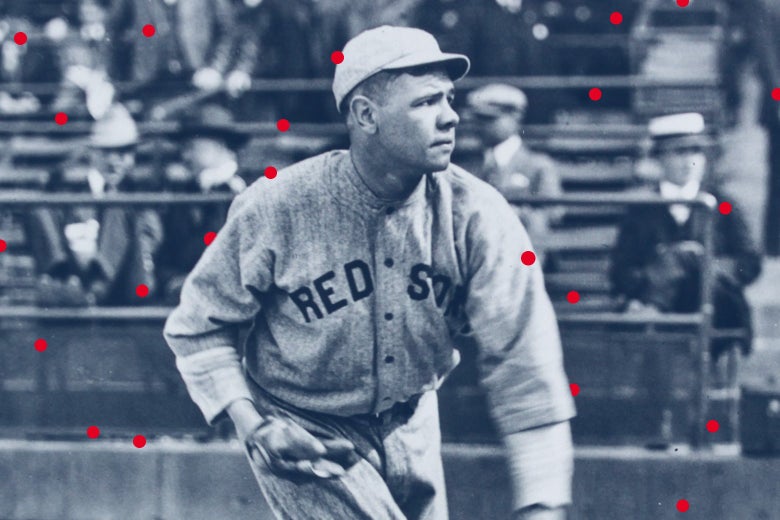

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Frances P. Burke/Wikipedia.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

This piece is an adapted excerpt from War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith. Copyright © 2020. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group Inc.

In the spring of 1918, the Great War spawned a sports revolution and a pandemic. The early signs of change could be seen that March in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where Babe Ruth, a 23-year-old moon-faced German American, discovered the thrill he felt—and the joy he brought soldiers—swinging his mighty “war club.” At the same time, the first wave of the so-called “Spanish Influenza” swept through the resort town. The question for the gregarious, handshaking, backslapping Babe was whether he could survive the outbreak long enough to fulfill his promise.

By the time the Boston Red Sox began spring training, the team had already lost 11 players to the armed forces, and they sorely needed his services in the field and at the plate. In the season to come, Ruth, a dominant pitcher, filled the void for the Red Sox and America. Unlike most hitters who choked up on the bat and chopped at the ball, he unleashed an uppercut swing with all his might, launching baseballs into the ether. Swinging for the fences, Ruth would become the first real slugger, a one-man revolution, single-handedly pounding the game into an entirely different shape.

During one exhibition against the Brooklyn Dodgers, Babe displayed his innovative hitting approach before several hundred doughboys. On March 23, both teams left their quarters in Hot Springs early in the morning, took a train through the hills of Arkansas to Little Rock, and then traveled by automobile to the Army cantonment at Camp Pike for the game.

No sooner had the Red Sox arrived at Camp Pike and taken the field to warm up than dark clouds swept in and the skies opened, followed by lightning flashes and low rumbles of thunder. Although the managers canceled the contest, they still held batting practice, and Babe’s performance was thoroughly entertaining for “the khaki boys.”

To the immense enjoyment of the soldiers, he drove five balls over the right-field fence. The feat was so unusual that a Boston American headline blared: “Babe Ruth Puts Five Over Fence, Heretofore Unknown to Baseball Fans.”

The stories of Ruth’s home runs overshadowed a curious development on the team. During their time in Hot Springs, two of his teammates, George Whiteman and Sam Agnew, fell ill with “the grippe,” and several other players soon became sick. “The reign of the grippe and sore throats continues,” noted Boston Globe reporter Edward Martin. That same day, Henry Daily of the Boston American reported, “A perfect epidemic has run through the entire city, and almost everyone complains.”

No one on the Red Sox seemed too concerned about influenza decimating the team. Looking back, it’s not surprising that some players contracted the flu after socializing among soldiers at Camp Pike and in Hot Springs, a “spa city” of bathhouses and saloons. It’s likely that influenza struck Hot Springs when troops visited the town. Shortly before, an initial influenza outbreak began in Haskell County, Kansas, and spread to nearby Camp Funston. From there the infected soldiers carried influenza from Funston to other camps, infecting civilians along the way.

Yet, the Red Sox encounter with influenza did not end in Hot Springs. The pathogen followed Babe all the way to Boston.

On May 19, 1918, the first warm day of the year, Ruth took his wife, Helen, to Revere Beach for an afternoon outing. Located just north of the city, it was the nation’s first public beach, a working-class “people’s beach” that featured amusement rides, a boardwalk, and an elaborate pier. Babe spent the day in the sun, eating a picnic basket full of sandwiches and drinking warm beer, swimming on a full stomach, and enjoying his own celebrity by playing a game of baseball in the sand with some locals. He couldn’t have been happier.

Later that night, Ruth complained of a terrible fever. His temperature climbed to 104 degrees, his body ached, he shivered with chills, and his throat throbbed. He had all the symptoms of the flu, a condition that he shared with millions of other Americans in the spring of 1918. Although some people died, most struck with the “spring flu” struggled through the aches and sweats of the fever and recovered.

Rumors shot through Boston that “the Colossus … worth more than his weight in gold” was on his deathbed.

Ruth might have been among the lucky ones, but the Red Sox physician made matters worse. The day after Ruth’s trip to the beach, he was scheduled to pitch. He showed up at Fenway looking like a ghost, feeling miserable, obviously ill, and in no condition to take the field—but determined to throw nonetheless. Dr. Oliver Barney “took a look at the big fellow, decided that the trouble was something more than a mere sore throat, and recommended four or five days of complete rest in bed.” Red Sox manager Ed Barrow agreed, and immediately crossed Ruth’s name off the lineup card and sent him home with the doctor, who liberally swabbed his throat with a caustic compound of silver nitrate, probably a 10 percent solution. In fact, he painted Babe’s throat too liberally. Among the dangers of using the solution to treat tonsillitis, the standard American Journal of Clinical Medicine noted in 1914: “Caution: Great care must be exercised that no excess silver-nitrate solution oozing from the swab drops into the throat, lest serious results follow; for as we know, cases are on record in which edema [swelling] of the glottis, severe spasms of the larynx and other spastic affections of the throat, even suffocation, resulted from such accidents.”

The treatment hit Ruth like a line drive to the throat. He choked and gagged, writhed in pain, and finally collapsed. Immediately, he was rushed to the eye and ear ward of the Massachusetts General Hospital. There a physician packed his inflamed throat in ice. Soon rumors shot through Boston that “the Colossus … worth more than his weight in gold” was on his deathbed.

Two days later, the news from Massachusetts General significantly improved. “Babe’s great vitality and admirable physical condition have started to throw off the aggravated attack of tonsillitis,” noted the Boston Herald and Journal. “The prophecy now is that the big lad will be out of the hospital in four or five days” and would be ready by the end of the month to travel west with his teammates.

Ruth made a full recovery. During May and June, he cracked 11 home runs, more than five entire American League teams would hit that year. In the context of America’s deadly attacks on the Western Front, his awesome power—his violent, full-bodied swings—resonated with the country’s glorification of unrestrained force.

Yet the spring flu persisted throughout U.S. training camps and followed soldiers aboard transport ships set for France. By May, hundreds of thousands of troops—countless infected—sailed across the Atlantic each month, carrying the virus into the packed trenches on the Western Front. There the virus mutated, and then a more lethal strain returned home later that summer.

Despite warnings from health officials about a citywide outbreak, the World Series between Ruth’s Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs still went on as planned, fueling the plague and infecting patrons at Fenway Park. Undoubtedly, crowded public events—three World Series games, parades, rallies, and a draft registration drive—fueled the epidemic, ultimately killing more than 4,800 Bostonians alone by the end of the year.

On Sept. 11, 1918, the day that the Red Sox won the title, Boston newspapers reported that 500 bilious sailors at Commonwealth Pier had contracted “the grippe.” The next day, 96,000 Bostonians stood in line to register for the draft—sneezing, coughing, and breathing on one another in crammed registration halls. In a matter of days, the contagion spread as fast as the fear of death.

Boston, a major shipping port where soldiers and sailors came and went, would soon become the epicenter of a pandemic that killed more than 675,000 of America’s 105 million inhabitants. Worldwide, the figures are even more stunning: Somewhere between 50 million and 100 million died.

After the season ended, Ruth returned to Baltimore, his hometown. In early October, the Baltimore Sun reported, “The great and only Babe Ruth has fallen victim to the ‘Spanish’ flu.” Ultimately, he recovered from a second fight against the affliction. Finally, after being dogged by the flu for an entire season, Babe was safe. But for much of America, the horrors were only beginning.

by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith. Basic Books.

Listen to an episode of Slate’s sports podcast, Hang Up and Listen, below, or subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Play, or wherever you get your podcasts.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2QJWTNJ

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言