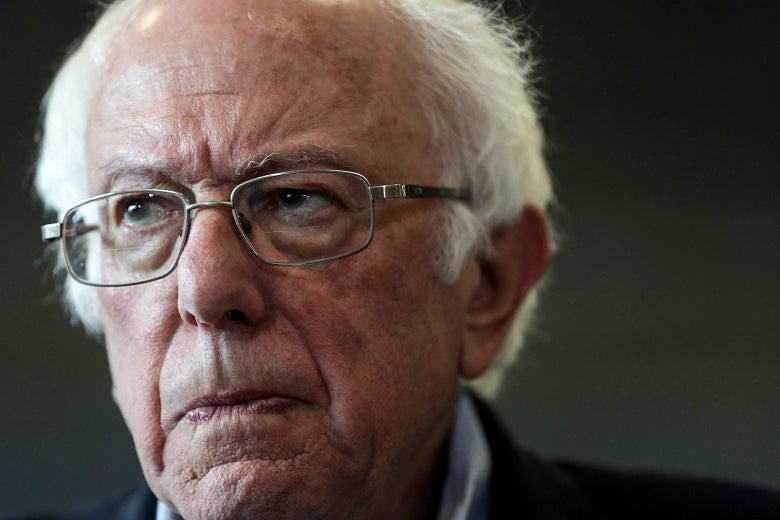

Bernie Sanders in Las Vegas on Saturday.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

In early October, while campaigning in Nevada, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders was rushed to the hospital experiencing chest pain. He was admitted and had two drug-eluting heart stents placed in his left anterior descending artery—the one commonly known as the “widow-maker.” Three days later, the campaign released a statement confirming what any practicing physician could deduce—the senator had experienced a heart attack.

In the months since, he’s emerged as the frontrunner in a competitive race, keeping up a busy campaigning schedule and performing energetically in the debates. The news of his heart attack largely receded from the coverage of the race, and he recently announced he won’t be sharing more information about it, despite his October promise to make all of his medical records public. (It’s worth noting that in our fragmented system, the concept of a “full” medical record is actually a kind of fantasy. What would prove useful here would be more comprehensive original records, not just summaries; in Sanders’ case, even just a few key documents from the past year expanding more on what happened in October would be clarifying.)

If Sanders were to honor his promise to release his “full” records, a nearly complete analysis of his short-term health risks could be made. As a physician who assesses these types of risks on a daily basis, I believe that all candidates, especially older ones—and particularly Michael Bloomberg, who has just revealed that he has heart disease significant enough to warrant coronary stenting in the past—should level with the American people and release not just summaries from their personal physicians but comprehensive and detailed medical records. But even with the information we have now,

it’s possible to take a meaningful look at the risks of further health problems cropping up during the senator’s campaign. I considered the risk that, between now and Nov. 3, Sanders might experience any of the following: a second heart attack, another life-threatening emergency, any event that would require hospitalization (including any “false alarm”), or even death. The risk is not trivial, and is worth explaining in full.

First, there appears to be little evidence that Sanders’ current health is a hindrance to the daily rigors of a national campaign. Considering the extent of his heart attack in October, he appears to be doing well, able to campaign vigorously, and likely up to the demanding position of president, from an endurance standpoint at least. Nor is his life expectancy the central question, though, yes, his remaining expected life span dropped from around 10 to five years after his heart attack. But his one-year risk is low, meaning his chance of surviving the campaign is good. When Sanders entered the hospital in October (given what we’ve been told by his doctors), his calculated six-month risk of death was rather harrowing, likely between 11 and 19 percent. Fortunately, by virtue of surviving his initial hospitalization, and the incident-free intervening four months, those numbers have improved, to better than 95 percent.

The documents that have been released by the Sanders campaign provide information that seems positive: Two months after his heart attack, for example, the senator performed 50 percent better on an exercise stress test than men of his age who had similar conditions. But compared with men his age without known heart conditions, his exercise capacity was described by his own physicians as merely average. So, what we can say is that whatever statistical edge Sanders may have had over the general population of his geriatric peers in September was forfeited in an instant in October. He is now, cardiovascularly speaking at least, a typical old man.

What’s the risk that nonfatal emergencies could take him off the trail between now and Nov. 3, the optics of which would be important to the race, even if he mounted another successful and speedy recovery? We have good ways of estimating that chance. Granular data from one of the most influential cardiovascular trials of the 21st century shows that upon release from the hospital after a heart attack like Sanders’, the 12-month risk of either another heart attack, a stroke, or death deemed to have been caused by another cardiovascular problem in men 75 or older was at least 18.3 percent, or a little better than 1 in 5. This is despite daily doses of clopidogrel, a drug Sanders now takes to help prevent these outcomes (though it also increases his chance of internal bleeding), as noted in the records he has released.

The good news for Sanders is that he’s fared well in the first four months after his heart attack, which is when about two-thirds of these complications generally occur. That means his risk for the remainder of the year is now likely to be around 6 percent. But because he hasn’t released the full record from his October hospitalization, we don’t know if that number is actually substantially higher or lower. Both are possible. Knowing the results of his first cardiac blood tests (which appear to have been abnormal, though the precise language we’ve been given makes this a little vague), the presence of certain key features on his electrocardiogram (the information his doctors released is conspicuously vague on this), and how long it was from the time he first experienced symptoms related to his heart attack to when his coronary arteries were stented open could markedly alter this estimate, in either direction.

In a presidential race, being hospitalized for any reason matters.

There’s another element to consider, behind the straight risk of another heart attack, stroke, or even death. In a presidential race, being hospitalized for any reason matters. So how likely is Sanders to require another hospitalization between now and November, even if none of these more serious cardiovascular events occur? Thanks to government-funded research of Medicare databanks, we can take a very close look at this. Using Medicare claims data, researchers at Yale analyzed millions of patients who suffered heart attacks like Sanders’. (As an aside, using adjectives like mild, moderate, or severe to describe Sanders’ heart attack is not helpful. What we can say is that these researchers were looking precisely at patients like Sanders who had experienced approximately the same problem as his, in the same time frame.)

Here’s what they found: From the day they left the hospital, the one-year risk of at least one rehospitalization for any reason in Medicare beneficiaries who suffered a heart attack like Sanders’ was about 50 percent (the baseline annual risk among his age cohort is more like 1 in 6). Again, by virtue of four incident-free months on the trail, that number is now lower for Sanders. But his chance of another hospitalization between now and November alone likely remains between 30–35 percent. While the daily risk is low, around 0.17 percent, we have more than 250 days to go until Election Day. The risks add up.

What’s the chance of a mere ER visit that doesn’t end in hospitalization? Those statistics may exist, but I couldn’t find any publicly available information to answer that question (the team at Yale does not have these numbers). What we can say, though, is that the rate of ER visits within one year of a heart attack is bound to be substantially higher than the rate of rehospitalizations. This makes sense—if you feel a little off, and you’ve recently had a heart attack, you’re probably going to go get it checked out. In my experience with these patients, the most common diagnosis is, thankfully, a “false alarm.” (I do worry about whether an aversion to the optics around an ER visit during a campaign might have the opposite effect, preventing a candidate from seeking emergency care precisely when he needs it the most.)

So, those are the short-term risks. What are the long-term risks? Again, Medicare claims data, this time analyzed by researchers at UCLA and Duke, provides information. We know that at five years, about half of population who has had heart attacks like Sanders’ remains alive. Once he makes it a full year, his odds of surviving a first presidential term would be about 65 percent, and would be 40 percent for two terms. The risk of a second heart attack during his first term hovers at about 30 percent, and would reach about 50 percent by the end of a second term. (This risk of this outcome in particular might be much higher or lower, but the relevant data from his hospitalization from October remains under lock and key.)

How does Sanders’ risk of a medical emergency (or even the optics nightmare of a false alarm) stand in comparison with his competition? Right now, it is impossible to say. That’s because, unfortunately, we lack substantial (or any) records of the remaining candidates. (Sanders has actually released the most information about his health of any candidate.) Getting the records would be easy. A signed HIPAA release form is all that is needed. From there, external experts would be able to assess and provide further insight. While, in my opinion, these records would be unlikely to move the needle in favor or against any candidate most of the time, there are sure to be instances, either now or in the future, when voters will have benefited from that information.

Medical transparency in the age of the geriatric presidency is a good habit. Let’s start it now.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views and opinions of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Slate is covering the election issues that matter to you. Support our work with a Slate Plus membership. You’ll also get a suite of great benefits.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2uhjp8M

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言