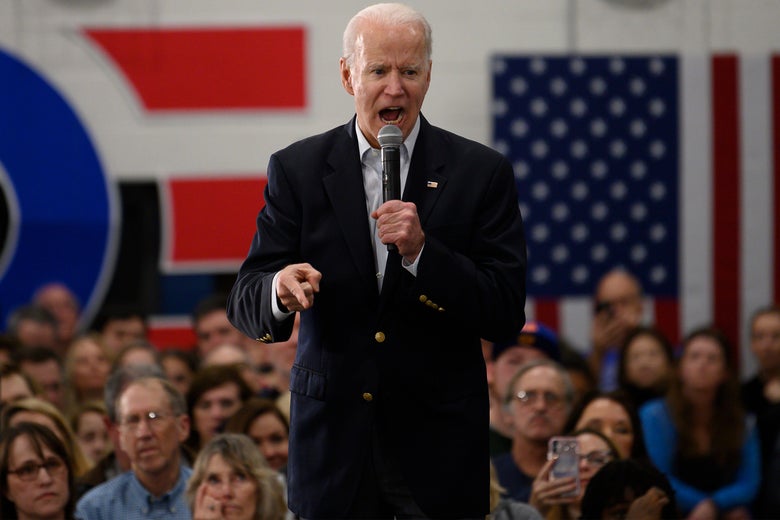

Joe Biden speaks at an event in Des Moines, IA, on February 2, 2020.

JIM WATSON/Getty Images

DES MOINES, Iowa—The weekend before voting began in the 2020 Democratic presidential contest opened with a ceremonial re-litigation of the 2016 Democratic presidential contest. Some members of the crowd at a Bernie Sanders rally in Iowa City booed at the mention of Hillary Clinton. When a panel moderator onstage asked them to stop, Rep. Rashida Tlaib, a prominent Sanders surrogate, encouraged them to continue.

Tlaib apologized the next morning. But the moment hit a nerve, and set the tone for what’s to come. It wasn’t just a re-litigation of 2016, it was a pre-litigation of 2020. Though the preseason segment of the 2020 nomination contest has been relatively polite compared to some Democratic primaries past (or any Republican primary), it’s at a boil just beneath the surface. If Iowa produces as its top two contenders Sanders and Joe Biden—who are first and second in both Iowa and national polling—the national race will have effectively lost what consensus options it had, to be divided instead between the avatars of two distinct wings of the party that see little resemblance in each other.

Since Sanders began rising in the polls, Sanders supporters’ paranoia about what the “establishment” may attempt to stop him has far outpaced any organized effort by top party actors to stop Sanders. The Sanders campaign has found it useful, though, ahead of a caucus where it only needs a modest plurality to win, to stoke these fears. One of Sanders’ most trusty surrogates, filmmaker Michael Moore, only had to mention the world “Democratic National Committee” at Sanders’ Saturday Cedar Rapids rally to elicit a round of boos.

“They’re so nervous and worried about Bernie,” Moore said. “There’s a story in Politico today, how some members of the DNC met today to discuss how to stop Bernie Sanders, how to let the superdelegates—remember them?—they’re going to try to figure out a way to have them vote on the first ballot at the convention.”

The story was a thin one, in which a handful of DNC members, out of several hundred, had texted each other about the possibility. Moore also decried the DNC’s decision to change debate criteria in a way that would allow Michael Bloomberg to participate in them, even though Bloomberg’s competitors have been wanting Bloomberg to join, as he’d make a useful target.

According to the Sanders campaign, the Cedar Rapids arena rally attracted about 3,000 people, making it the largest Democratic candidate rally of the cycle in Iowa. It certainly had a Ticketmaster-event feel unlike anything that other candidate was capable of producing. The free concert from Vampire Weekend following Sanders’ speech was likely a helpful motivator. And when frontman Ezra Koenig asked to the crowd, during the band’s set, where they were from, “out of state” earned a roaring response.

Each campaign’s social media team was showing off its INCREDIBLE crowd sizes at its final events of the weekend. Part of this is a trick: book a slightly smaller venue than the size you expect, and have people wait in line longer than necessary, and suddenly you have RIDICULOUS lines and PACKED overflow rooms. But undecided voters did also seem to be showing up more for events over the weekend, as their hours for making a decision ran out.

Tom Taylor, of Shell Rock, seemed stuck. He was a former Republican who switched parties to support Barack Obama in 2008, caucused for Bernie Sanders in 2016, and this time, was looking between Amy Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg, and Andrew Yang. I spoke to him Saturday at a Cedar Rapids rally for Elizabeth Warren.

He was searching for “moderation” and “compromise” in candidates, and didn’t seem interested in Warren at all, saying that he would prefer Sanders over her. When I asked what the difference was, he took a lengthy pause to consider his response. “Bernie is a little more laid back than Warren,” Taylor said. “I feel Warren is a little on the edge, too passionate.” He planned to caucus with “undecided” in the “first game of shells” at his precinct, and read the room from there.

Warren is passionate. She ran into her Cedar Rapids rally as her husband, law professor Bruce Mann, ran behind her, leading the family mascot—Bailey, the golden retriever—on a leash. She still devotes much of her rally to taking questions, at a point in the campaign some other candidates find it too risky for such spontaneity, and she can answer niche ones—one about how she would crack down on multilevel marketing schemes, another about banks wanting to tax credit unions—with exactness, almost jump-kicking around the stage as she recognizes an opportunity to discuss enforcement at the Federal Trade Commission.

Warren still has an outside chance of winning the caucuses, even though she’s slid in the polls since last fall following her debacle over Medicare for All. Watching her have complete control over a room, it’s obvious why she was, for that period last fall, the would-be unity candidate who could provide an escape from the looming clash between Sanders and Biden.

Warren, in her last hours in Iowa, clearly wanted that role back. In her opening remarks, she spoke well of nearly all of the middle-ground candidates who had left, including Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Julian Castro, Jay Inslee, and “Bullock, from Montana.” This was the morning after The Boo at Sanders’ rally, and Warren emphasized how proud she was to lead an organization that doesn’t say, “’It’s us and no one else.’ It’s a campaign that says, ‘Come on in.”

Amy Klobuchar, too, was making one last attempt to burst the Biden-Sanders duopoly, though from a more Buttigieg-esque, centrist position. Klobuchar was racing across the state on Saturday and Sunday, trying, as she told a (STANDING ROOM ONLY) crowd at a Best Western in Cedar Rapids, to fit 10 days of campaigning into two.

The undecided voters to whom I spoke to there were all choosing between either Klobuchar, Biden, or Buttigieg. And for those trying to differentiate between the three, she offered a couple of different arguments. It wasn’t necessary to name names.

“I think we should put someone at the top of the ticket that actually has the receipts,” Klobuchar said. “It is one thing to talk about winning in rural areas… it’s another thing to have actually done it.” Buttigieg, who lost his only statewide race in 2010, had been doing a tour of more rural Iowa areas in the final days of the campaign. “I think we need to put someone in charge of this ticket that has the nimbleness on the debate stage,” she continued, “to be tough enough and quick enough to take on Donald Trump.” Nimble isn’t exactly how one might describe Joe Biden’s debate performances.

It’s also not how you would describe speaking aloud about how you might jump late into the presidential race, while you’re supposed surrogating for Joe Biden, at the epicenter of global political media the day before the Iowa caucuses: the Renaissance Savery hotel in downtown Des Moines. But there John Kerry was, reportedly blabbing about what he would have to do to get in the race given “the possibility of Bernie Sanders taking down the Democratic Party.”

Whatever the would-be Iowa caucus-goers may have been hearing in the OVERFLOWING halls, from the full array of candidates trying to close the deal, thanks to Kerry, the national story came to a close with the focus again on the big two, Sanders and Biden: the one a little more paranoid than before, the other a little more anxious.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/31oFYED

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言