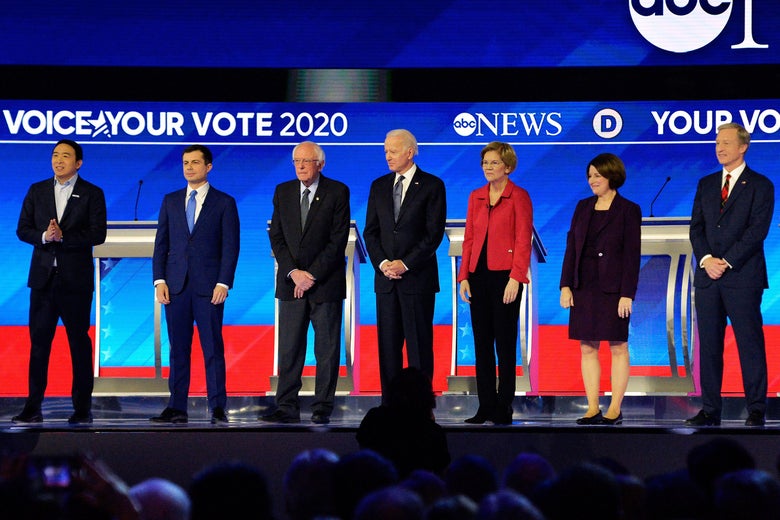

Democratic presidential hopefuls arrive onstage for the eighth primary debate of the 2020 presidential campaign season.

JOSEPH PREZIOSO/Getty Images

By Friday evening, I was already over it. The weeks run stormy during election season and this one in particular was a gale, a hurricane of major events swirling in rapid succession. Iowans caucused on Monday, and Caucus Monday still hadn’t found its ending on Tuesday when the president delivered his State of the Union address, or the next day when he was acquitted in his impeachment trial. I can’t recall what, if anything, happened on Thursday. But as the television droned in the background, and I hurried around my kitchen trying to get dinner into the Instant Pot, I knew that it was debate night which by some cruel DNC joke was happening on a Friday—Friday!—evening and I was exhausted.

I don’t think there’s any question, George, that after this week there’s a real threat that Donald Trump can get reelected.

I chopped chuck roast and sighed.

I’m not interested in the labels. I’m not interested in what Republicans are going to say. I’m interested in the style of politics that we need to put forward to actually, finally turn the page.

My eyes rolled as I sliced the celery, onions and carrots.

This is about our government. This is about our democracy. This is about our future.

I added the tomato juice and seasonings to the pot. Thus far, the debate was going as expected. Everyone was spitting a version of their prepared statements and landing their applause lines. But as I clicked the pot’s lid into place, I heard a rise in Tom Steyer’s voice. He had been discussing Republican attempts to pack the courts before he decided to try and rise above the question, to challenge the moderators for asking policy questions on which the candidates mostly agree instead of explicitly asking who can unite the Democratic Party to beat President Donald Trump. I presume this sliver of a thought got him thinking about the racial diversity of the Democratic base—a stark contrast to the stage—and ignited his self-given obligation to mention the fact that race hadn’t even come up yet:

We have not said one word tonight about race. Not one word. Are you kidding me? We have the most diverse party. We have a very diverse country. We have a very diverse party. The heart and soul of this party is diversity, Black people, Latinos, AAPI people, Native Americans and white people. But for goodness sakes, pull it together. We’re talking about something different. The question we have is how are we getting that diverse group of people to the polls? What are we saying? Everybody on this stage feels the same way about a woman’s right to choose and economic justice. The question is how do we beat Trump? How do we take down these Republicans?

Steyer didn’t exactly connect the idea of acknowledging race to the subject he was trying to talk about. But his swerve did jerk the conversation, which had drifted among who could best unite the country, foreign policy, and abortion, to the topic of racism in America. Soon after, the moderators—whether intentionally or by coincidence—began asking the candidates race-pointed questions.

Moderator Linsey Davis asked Pete Buttigieg about increased marijuana-related arrests of Black citizens during his tenure as mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and then pressed him when he dodged the question. This led Sen. Elizabeth Warren to criticize Buttigieg’s avoidance before she broadened the conversation out to advocating for race-conscious laws in housing, education, and entrepreneurship.

Andrew Yang, the lone candidate of color left onstage, leaped into the ring. “Elizabeth, with respect, you can’t regulate away racism with a whole patchwork of laws that are race-specific,” he said, and then invoked a rather incomplete version of Martin Luther King Jr. to argue that his own Freedom Dividend plan is rooted in King’s belief that a universal basic income would aid in the eradication of poverty.

Steyer jumped back in and yanked the conversation to reparations. He asked Vice President Joe Biden to disavow Democratic South Carolina state senator Dick Harpootlian, a Biden supporter who’d accused the chair of the state’s Legislative Black Caucus of being bought by Steyer’s money. Biden pointed out all the Black politicians who support him. Sen. Bernie Sanders popped over and claimed he had even more Black Caucus members in South Carolina backing his campaign. Steyer pleaded with the two to not to argue about “polls.” Biden reminded him that endorsements aren’t polls. Steyer demanded an answer on Harpootlian. Biden gave him one and pivoted to the importance of not taking the Black community for granted before laying out how much he has done for Black people throughout his career.

Fatigue jolted through me, as the events of the week compounded with the overwhelming whiteness of the stage. The Democratic contest had been winnowed from the most diverse primary field since Reconstruction to three people of color, two of whom were not on stage. And I don’t know bout y’all but watching white people shout over each other about who can, or will, do the most for Black folks can be exhausting. For a party that lays claim to such a racially diverse base, the presentation of mostly white contenders is jarring. It’s partially a malady of the DNC’s increasingly strict qualifications to land a spot on the debate stage. Candidates of color haven’t been afforded as many opportunities to make their case for addressing racism in America. To get on the debate stage, you need money and adherents. To get adherents, you need money and a spot in the debate.

A “food burn” alert blared across my Instant Pot as the portion of the debate dedicated to America’s longest-running psychodrama sped forward at full speed. Moderator George Stephanopoulos encouraged the candidates to keep at it: Warren was elated Democrats were talking about racism since it only seems to come up during election season. Klobuchar mentioned the abysmal maternal mortality rates for Black women. Steyer said he wants a commission to “retell the story of the last 400 years in America of systematic racism against African Americans.” Yang reiterated the need for a universal basic income. Buttigieg was noticeably silent.

Discussions of racism had dominated the stage for roughly 19 minutes. It wasn’t enough, and yet in some ways it was too much. It felt performative, but passionate dialogue about racism is necessary. As I stood there watching the television, however, I couldn’t knock the feeling that this conversation—as fervent as it was—existed as mostly a production of the white guilt that has manifested in response to an overtly racist incumbent.

Don’t misunderstand me, this is better than the alternative where they don’t mention racism and disparities at all. A new era of Black protest has forced politicians to be more vocal about where they stand on racism and how they intend to address the myriad problems that disproportionately plague said communities. Some of the remaining candidates have developed impressively substantive policy platforms that focus on uplifting Black folks. But former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro, Sen. Kamala Harris, and Sen. Cory Booker were raising those issues too—with the lived experience to further substantiate it. Yet their perspectives were missing.

The pot continued to beep as the mostly white stage, which seemed desperately aware of the collective responsibility to speak on behalf of the missing demographics, moved onto their next topic: Michael Bloomberg.

I shuffled back into the kitchen and tried to save my dinner, wondering how food burns in an Instant Pot anyway, and how a stage could be full of people talking about inclusion without including any Black people.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3bsp5ha

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言