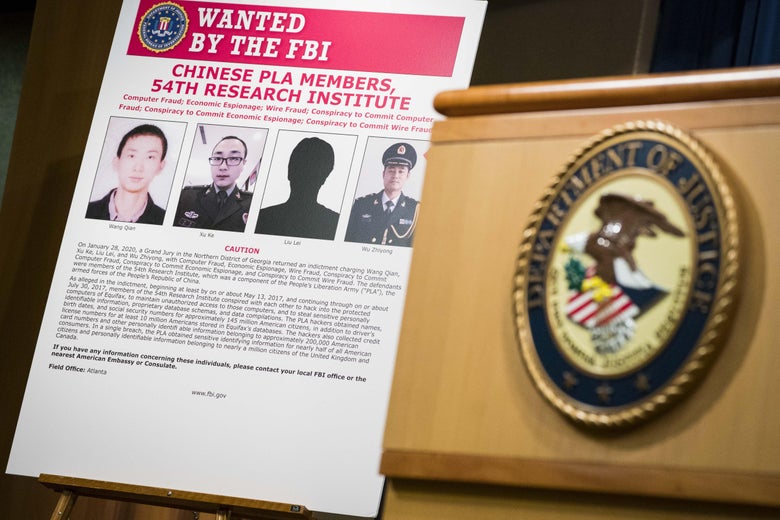

Attorney General William Barr held a press conference on Feb. 10 to announce the indictment of four members of China’s military on charges of hacking into Equifax.

Sarah Silbiger/Getty Images

On Monday, the Department of Justice released an indictment that alleges the Chinese government was behind the 2017 breach of Equifax that led to 147 million of people’s information being stolen. The indictment, which charges four members of China’s People’s Liberation Army with carrying out the breach, is, in a way, good news for those of us worried that our stolen information might be used to conduct identity fraud or financial theft. Historically, the Chinese government has not been very interested in stealing individuals’ money or working with organized crime groups who carry out financially motivated cybercrimes. Instead, the Chinese government appears to be collecting information for espionage purposes. Cybercriminals might be able to steal the Equifax data from the Chinese government, but truth be told, it’ll probably do a better job of protecting your information than Equifax did.

Back in July, Equifax reached a settlement for the breach, agreeing to pay between $575 million and $700 million to provide identity monitoring to the victims, or a cash payout of $125 to those who already had some form of identity monitoring in place. So many people claimed the $125 that the Federal Trade Commission started encouraging them to take the identity monitoring instead. But the fact that the perpetrators of the Equifax breach are unlikely to use that information for identity theft highlights just how unhelpful many of the identity theft protections built into the Equifax settlement will probably be for those who elected the free credit monitoring option. Whatever the Chinese government plans to do with this information—whether that’s extortion, identifying people in precarious financial positions who might be susceptible to bribery, or simply putting together more comprehensive dossiers on people of interest to them—Experian credit monitoring is unlikely to be a significant obstacle for them.

This was also true in the case of the 2015 U.S.

Office of Personnel Management breach, when the records of 21.5 million former and current federal employees were stolen from the U.S. government, including security clearance information and fingerprints. That breach was also attributed to the Chinese government, though China later announced it had arrested the hackers it believed to be responsible. In the aftermath of that incident, victims also received a lot of identity theft monitoring services but little that would do anything to protect them from the Chinese government (though, in that case, the CIA did remove officers from Beijing for fear that their covers might be blown). This points to a fundamental problem with how we handle data breaches: Practically all of our remedies for victims assume that the perpetrators are cybercriminals and are designed to protect victims from financial fraud rather than the broader and more nebulous set of consequences associated with cyber-espionage.

Cyber-espionage has been a big source of contention between China and the United States for several years now, with the U.S. alleging that the Chinese government steals U.S. intellectual property. Interestingly, the indictment released by the Department of Justice makes the case that the Equifax breach was not just an act of political espionage, like the OPM hack, but also an act of economic espionage. It’s a strange charge because personal information about individuals is more in line with traditional espionage activity, and it’s not clear exactly what trade secrets Equifax had that the Chinese government would have wanted.

The indictment specifies that the trade secrets stolen by the PLA members were “database schemas and the compilation of data within those databases owned by Equifax”—in other words, the stolen data and the databases used to store it. But the rest of the indictment makes clear that, in fact, the databases Equifax used to store the stolen data were nothing special and could be easily accessed using standard database queries. And the conception of Equifax’s customers’ personal data as a form of “trade secret” is so bizarre it really feels like the U.S. government grasping at straws to turn this into a case of economic espionage and thereby bolster its broader contention that China is busy stealing U.S. intellectual property.

Undoubtedly, intellectual property theft by the Chinese government has been a recurring issue for the United States. An earlier U.S. indictment, in 2014, charged five different PLA officers with acts of espionage directed at steel, solar, and nuclear power companies that more clearly seemed to target trade secrets. And even that indictment was only able to identify one particular file—which described the piping design for a nuclear power plant and was stolen from Westinghouse—that constituted actual economic espionage. This distinction between political and economic espionage was important to the United States government at the time because it was attempting to establish a norm for cyberspace that political espionage was acceptable but economic espionage—or governments stealing companies’ trade secrets to benefit their own, domestic companies—was not.

But the Equifax breach looks an awful lot like political espionage. The stolen information is very far from nuclear power plant plans—it’s hard to see how it could be classified as intellectual property or provide Chinese companies with a clear competitive advantage. The Equifax indictment states, by way of justification for its economic espionage charge:

In connection with the management and protection of its databases, Equifax developed and maintained proprietary compilations, designs, processes, and codes that constituted trade secrets. … This trade secret information included the above-described personally identifiable information Equifax had acquired at great effort and expense and that enabled it to operate its business and compete in the marketplace—that is, its data compilations—as well as the means by which Equifax accessed and analyzed that information, that is, its database schemas.

In other words, the Department of Justice classified the personal information of 147 million people as a “trade secret” for the purposes of this indictment (to say nothing of the insecure database Equifax was using to store that information).

It’s a strange formulation that undermines an otherwise informative indictment detailing how the PLA infiltrated Equifax and the tactics it used to try to cover up its actions. Clearly, a great deal of valuable investigative work went into this indictment, and there’s a lot that both the U.S. government and U.S. companies could learn from the facts laid out in it about how to better protect against cyber-espionage in the future. But calling everything China does economic espionage and condemning it as such will be about as helpful as 10 years of credit monitoring from Experian.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2vo8cDL

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言