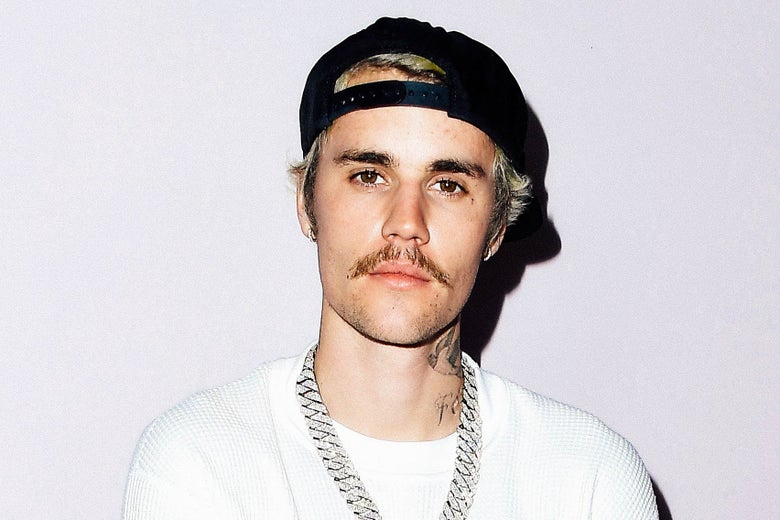

Justin Bieber in Los Angeles on Jan. 27.

Steve Granitz/WireImage

Can it be mere coincidence that, at the start of the year that follows HBO’s Michael Jackson documentary Leaving Neverland, both of the biggest new pop-star documentaries are largely about the psychological aftermath of child stardom? In Taylor Swift’s Miss Americana on Netflix, she discusses for the first time how being a teen celebrity arrested her emotional and intellectual development. And in Justin Bieber’s Seasons on YouTube—which admittedly is less successful at presenting itself as a stand-alone documentary, rather than a making-of promotion for his new album Changes—he admits that his anxieties and the acting out and drug addictions that accompanied them in his late teens reached a point where staff members were checking on him in the night to ensure he was still breathing. In scenes that feel like all-too-direct reminders of Jackson’s own eccentric therapeutic regimes, we see Bieber being zipped into a hyperbaric oxygen chamber. And around the peripheries of both Swift’s and Bieber’s stories, we witness some of the adults who’ve been overseeing their careers since early adolescence getting them back on their show-business schedules after periods of retreat—acknowledging their worries but never any culpability for plunging these kids into situations way beyond what their developing brains could process.

Last time around, Swift and Bieber each put out albums that tried to deal with their ordeals of public opprobrium, with her 2017 Reputation and his 2015 Purpose. Though commercially successful, these albums’ receptions were otherwise disappointing. In Swift’s documentary, she is shown coping stoically with the fact that the Grammys passed her over for major-category nominations after her two Album of the Year wins. Seasons begins with Bieber canceling the last leg of the Purpose global tour because of some kind of nervous collapse. In the end, they each return with records that invest their hopes for renewal and redemption in domestic love and stability. For Swift, on last year’s Lover, it’s her relationship with British actor Joe Alwyn, which mostly has been kept quite private outside of her autobiographical lyrics. For Bieber, on Friday’s Changes, it’s his rather more demonstrative romance and marriage to model Hailey Bieber (née Baldwin): At a recent London listening session for the new album, he hubba-hubba’d about the pair’s sex life and then, painfully, asked all the single people in the room to raise their hands so he could promise he was praying for them.

Personally, my soul is a mass of blood and marshmallow, so both love stories make me sincerely glad for the two stars. But not quite in the same ways. While Swift and Bieber are bound by a bizarre set of experiences that only a handful of people in world history could ever truly understand—Renée Zellweger just won an Oscar for portraying one of the few who could—they’re vastly different individuals. It’s not just that Bieber is only a decade out from being the “Baby” that shrieking fans met when he was 15, while Swift is now a woman of 30. It’s that she was always a willful upper-middle-class prodigy from a Christmas tree farm in Pennsylvania, while he was a kid from small-town Ontario poverty who was talent-scouted away into a whirlwind. Swift’s narration of her own story, in both song and interviews, radiates self-possession. Meanwhile, the way Bieber, in the YouTube series, reaches for words from his therapists and his church, and, in lyrics, leans on his co-writers and pop clichés—all while physically he twitches and goofs and nestles into his wife as if she were a sort of maternal oxygen chamber herself—is a lot less reassuring. He honestly does seem like an incredibly sweet guy, just as everybody in Seasons says, one with a huge heart, a sometimes astonishing vocal talent, and a puppylike distractibility by fast-moving things. But it’s a lot harder to feel confident he’s going to be OK.

The album is most successful when he makes the R&B that he’s always loved most—there was a reason Usher was the person who ushered him into the music industry.

I don’t mean to reduce Bieber’s album to a set of symptoms. The urge to do so comes from the way that child stardom also infects the rest of us, making onlookers feel falsely that we’ve been part of the star’s coming of age. That is part of the abusive dynamic I want to reject. It’s tempting, for instance, to call to the stand Bieber’s ex and Swift’s close friend Selena Gomez, whose new album Rare addresses what she now calls their sometimes emotionally abusive relationship, within which Bieber’s now acknowledged he acted “crazy” and “reckless.” Gomez’s record exudes a vitality borne of self-discovery, something Changes stretches for but mostly misses. I could attribute this split to the fact that Gomez, like Swift, is able to seize upon a 21st-century template of millennial feminist self-love and affirmation, something for which Bieber, as a straight white dude mostly adrift in the flotsam of his own bad decisions, has no analogue. On the other hand, one could as easily diagnose that Gomez is benefiting from a set of producers who are excited to engage with her growing artistic range in an auspicious moment for Latinx crossover pop—just as Bieber on Purpose reaped the rewards of having the right kind of supple tenor for 2014–15 electronic-dance-music producers to layer into their singles. In the half-decade between his previous album and this one, Bieber has had his biggest impact as a guest artist, shepherding tracks such as DJ Khaled’s “I’m the One” and 2017 song of the summer “Despacito” to the top of the charts. He’s become kind of a special effect.

I’m somewhat persuaded by GQ critic Max Cea that this motif continues on Changes—that when Bieber is joined by the likes of Quavo, Post Malone, Travis Scott, Lil Dicky, and Kehlani, the burden of being Justin Bieber feels somewhat lifted. Rather than testimony to the stations of the child-star cross, the songs can just be songs. Much of the rest of the time, Changes is snoozy and noncommittal, in keeping with the reading from critics like the Guardian’s Alexis Petridis and the New York Times’ Jon Caramanica that Bieber is trying to make a “hiding in plain sight” non-comeback comeback, that he is hoping to reconnect with fans without sparking the pop frenzy that “Sorry” or “What Do You Mean” did in 2015. The difficulty with that account is not only Seasons and the forthcoming tour but “Yummy,” the horny bubblegum single for which he released no less than seven videos (not counting the video game) and which appears on the album in two different versions.

“Yummy” is the worst major single of Bieber’s career. But let’s write that off as an unfortunate meeting of Bieber’s current sexy-wife-guy personal fixation and his music-industry minders’ desire to throw a bone to the thirsty fans of old. Mostly Changes is at its best when it echoes Hailey’s statement in Seasons that you can’t stay mad at Justin because he’s so damned cute. He’s cutest when he makes the R&B that he’s always loved most—there was a reason Usher was the person who ushered him into the music industry.

“Intentions,” with Quavo, is great as long as you don’t listen too hard to its vision-boarding lingo, and it’s difficult not to appreciate its blatantly amends-making video, in which Bieber has homeless and low-income people weeping over the charitable gifts he dispenses but also lets street poets and shelter managers speak their truths. “Habitual,” co-produced by Puerto Rican reggaeton giant Tainy, is the best of the album’s several pulsing synth-wash tracks, especially because it acknowledges that Bieber’s spousal romance may or may not be his latest “vice.” “Available” is utterly too adorable for acknowledging his desperation being greater than his wife’s, and urging her to get home to him soon but also “don’t speed.” Travis Scott is a minor presence in “Second Emotion” compared with the Smokey Robinson reference that fundamentally guides it. And Bieber delivers his most bravura vocal on the acoustic guitar–driven “E.T.A.,” which ideally would have ended the album rather than the several limper retreads that follow it. On all these tracks, his voice slides and sidesteps between notes as though he knows shortcuts that leave most other singers sounding like muggles who can’t perceive Platform 9¾ and instead have to take the commuter train.

However, whatever he, Hailey, and his closest studio collaborators, such as producer-singer-songwriter Poo Bear, would most like to be putting out is still compromised by manager Scooter Braun (Swift’s own most recent enemy of choice) and Bieber’s indentured relationship to UMG–Def Jam–RBMG. I don’t claim to understand that set of entanglements. But until Bieber can emancipate himself from them, it will always be hard to, well, “beliebe” in him as something more than a musical unicorn who’s internalized his role as a pack animal. Changes fails to relieve this listener’s distress that as someone who surely, hopefully, has the practical means to escape, Bieber feels too beaten down to cut the strings and say—to reference another cluster of unthreatening-boy-star casualties—bye, bye, bye.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3bNtwmB

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言