2020年1月31日 星期五

Apollo 14 Heads for Home

Watch LeBron James’ Heartfelt, Unrehearsed Tribute to Kobe Bryant

Now, I’ve got something written down. You know, they asked me to stay on course or whatever the case may be. But Laker nation, man, I would be selling y’all short if I read off this shit, so I’m gonna go straight from the heart.

The first thing that come to mind, man, is all about family. And as I look around this arena, we’re all grieving, we’re all hurt, we’re all heartbroken. But when we’re going through things like the best thing you can do is lean on the shoulders of your family. And from Sunday morning all the way to this point … now, I heard about Laker nation before I got here last year, about how much of a family it is, and that is absolutely what I’ve seen this whole week. Not only from the players, not only from the coaching staff, not only from the organization, but from everybody. Everybody that’s here, this is really, truly, truly a family. And I know Kobe and Gianna and Vanessa and everybody thank you from the bottom of their heart, as Kobe said.

Now I know at some point we’re going to have a memorial for Kobe. But I look at this, I look at this as a celebration tonight. This is a celebration of the 20 years of the blood, the sweat, the tears, the broken-down body, the getting up, the sitting down, the everything, the countless hours, the determination to be as great as he could be. Tonight, we celebrate the kid who came here at 18 years of age, retired at 38, and became probably the best dad we’ve seen over the last three years, man.

Tonight is a celebration. Before we get to play. Love y’all, man. Kobe is a brother to me. And from the time I was in high school, from watching him afar, to get in this league at 18, watching him up close. All the battles that we had throughout my career. The one thing that we always shared is that determination to just want to win, and just want to be great. And the fact that I’m here now means so much to me.

I want to continue, along with my teammates, to continue his legacy, not only for this year, but as long as we can play the game of basketball that we love because that’s what Kobe Bryant would want.

So in the words of Kobe Bryant, Mamba out. But in the words of us, not forgotten. Live on, brother.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/31eNrGb

via IFTTT

Help! I Helped My Sister Burn Her Wedding Dress. Now My Other Sister Won’t Speak to Me.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Bogdan Kurylo/iStock/Getty Images Plus and Prostock-Studio/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

To get advice from Prudie, send questions for publication to prudence@slate.com.

(Questions may be edited.) Join the live chat every Monday at noon. Submit your questions and comments here before or during the live discussion. Or call the Dear Prudence podcast voicemail at 401-371-DEAR (3327) to hear your question answered on a future episode of the show.

Dear Prudence,

My two sisters and I are all close in age. “Chloe” got engaged first but has put the wedding off due to grad school. “Zoe” got engaged a few months afterward and was looking at a whirlwind wedding. She bought the dress and then caught her fiancé cheating on her. I was with Zoe at the time, and she was devastated. We got drunk and emotional, and Zoe decided to burn the dress along with some of her ex’s things. I was just happy to see Zoe stop crying. We held a “ceremony” where she cleansed herself of everything that came from him and posted a picture to a private social media account. Chloe texted me in a rage: Why had I let Zoe ruin “her” dress? Chloe thought Zoe should have given her the dress since they are similar in size and said she was owed it since her wedding budget was already stretched thin.

I told her that was the most selfish thing I have ever heard and that she needed to get some perspective. She told me Zoe and I “don’t get” how hard her life is. I blocked her number. Chloe has neither apologized nor mentioned anything to anyone. She’s been very cold to me ever since, and everyone else in our family has noticed. She stirs the pot by saying “She knows what she did” about me, and I get asked why we are fighting. I haven’t revealed the truth, since it will hurt Zoe. She is still angry in general and might actually throw something at our sister’s head. At the least, she would probably refuse to attend Chloe’s wedding. What do I do here, other than remind my sister I have the texts?

—Burned

I can appreciate your motives for wanting to contain the fight, not least because you worry Zoe will blow up and cause everyone more problems. But I just don’t think this is sustainable in the long run, especially since Chloe’s already hinting that this is your fault and has demonstrated she’s comfortable behaving unreasonably. My worry is that if you try to keep things quiet, she’ll get her version of the story out first—and it’s likely to be a lie. Even if you don’t want to let Chloe’s possible future actions dictate what you do, there are other reasons to consider talking to at least Zoe. For example, are you prepared to attend Chloe’s wedding (assuming you’re still invited) under present conditions?

But before you consider whether to answer your relatives’ questions, I think it’s worth pushing Chloe to have one more conversation with you, even though she’s demonstrated pretty awful judgment thus far. “I love you, and I don’t want this to be what drives a wedge between us. It was important for Zoe to be able to get rid of something that represented her cheating ex. It wasn’t a statement about how hard your life has been, and I don’t think she owed it to you. If you’re willing to apologize and let this go, I am too. I really hope you want to, because I don’t want to fight about this anymore.” If she fails to course-correct, it may be necessary for you to talk to Zoe about it so she’s not put in the middle of you two. But break the news to her as gently as possible, without elaborating, and don’t show her the text messages unless you absolutely have to. Just because you have to tell her something difficult doesn’t mean you have to go for the most painful option.

* * *

Help! I Can’t Stop Snooping On My Former Job.Danny M. Lavery is joined by attorney Jason Carini on this week’s episode of the Dear Prudence podcast.

Dear Prudence,

I’m a woman in my 30s who’s always struggled with sleep—it often takes me an hour or more to fall asleep. My boyfriend and I have been together for two years, and he’s my first long-term relationship. When he first starting staying the night, I noticed I couldn’t sleep until he came to bed. We’ve been living together for a year now, and it’s still the case! I’ve tried going to bed earlier, going to bed later, taking melatonin, even taking CBD oil (it’s legal here), but nothing works. I think it’s awful to ask him to go sleep earlier just because I need the rest, but sometimes he’s up until 12:45 a.m. when I have an early meeting the next morning, and I’m a zombie on no sleep! Is it unreasonable to ask him to come to bed a little earlier (we’re talking midnight, not 10) on nights when I have important work to do the next day? Is there a third option I haven’t thought of?

—Counting Sheep

If you always woke up when your boyfriend came to bed or that the noise of hearing him move around in the kitchen or living room kept you up, I’d have a different answer for you, but it doesn’t sound like that’s the case. But asking him to come to bed 45 minutes sooner than he might otherwise the night before a big meeting is a reasonable request, provided you’re able to give him a heads-up a day or so in advance. Your sleep matters a great deal, and you have every right to prioritize it and find other strategies that help you get the hours you need. How did you fall asleep before you met your boyfriend? Melatonin and CBD oil may be fine, but they’re also slapdash over-the-counter remedies. It might be time to talk to your doctor and ask for a recommendation for a sleep specialist. It may take a bit more time and attention to figure out what other elements you need to fall and stay asleep—different medication, a body pillow, eye mask, earplugs, white noise machine, sleeping in separate rooms, all of the above, none of the above—but you’ll need more than just your boyfriend’s cooperation to really address this. After all, if you two broke up tomorrow, you’d still want to get a solid night’s sleep.

Dear Prudence,

I am a divorced mother of two kids, ages 7 and 5. I have been in a wonderful relationship with a widower for about four years now, living together for two. He has a lovely 11-year-old daughter. We have managed to blend our family pretty seamlessly. I am in a place where I am ready to get married again, but he still wants to wait. That’s a discussion for another day, though.

Here is my dilemma: I have been considering getting a small tattoo to honor my two kids (like a number 7 since both of their birthdays are 7’s, not initials or their names or anything). I’m curious if my boyfriend’s daughter will feel hurt or left out if the tattoo has nothing to do with her. How do I proceed here? Do I just not get the tattoo? Do I do what feels right to me, even if my boyfriend and his daughter might feel slighted?

—To Tat or Not

If you’re just talking about getting the number 7 tattooed on your body, I don’t think you should worry too much about your boyfriend’s daughter feeling slighted. It’d be one thing if you were proposing getting both of their names or full birth dates but not hers, but a single, small 7 (which is already pretty commonly associated with luck) doesn’t strike me as especially exclusionary or divisive. Go for it! Plus, with tattoos, most people can’t stop at one, so maybe at some point you’ll want to get something that represents your entire blended family. (Or maybe you’ll decide to hold off until you and your boyfriend have a more serious conversation about what long-term commitment looks like for you.) Tattoos are fun! Go for it.

Catch up on this week’s Prudie.

More Advice From Care and FeedingMy 8-year-old son is a very messy eater. Naturally, I blame myself for using baby-led weaning instead of spoon-feeding him baby food, because he still wants to eat everything with his hands. Yogurt, cereal, spaghetti, macaroni and cheese—he starts out with the utensil but eventually starts eating with his fingers. After every meal, I have to sweep under the table and wipe down the table and chair, which he had been touching with his disgusting hands. I thought this would all be over by now! He’s in third grade, and his other friends are not like this. I’m so tired of nagging him to sit over the plate or to stop eating with his hands or to use a napkin. I know he’s trying, but his mind is just elsewhere, not on the mundanity of eating thoughtfully. It also ruins my appetite. Any advice?

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2GOrkNn

via IFTTT

What Have Book Publishers Learned From the American Dirt Controversy?

The Flatiron Building, symbol of Flatiron Press, publisher of American Dirt.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Aditya Vyas on Unsplash.

What lesson are book publishers taking away from the controversy raised by American Dirt, Jeanine Cummins’ novel about a Mexican woman and her son seeking to cross the border? Will the furor change the way editors think about acquiring novels, or does the book’s sales success—it’s currently No. 2 on Amazon’s bestseller list—obviate those concerns? I asked several editors at Big Five houses (Hachette, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, and HarperCollins)—all of whom only felt comfortable speaking candidly if they could remain anonymous—what went wrong in the publication of American Dirt, how it might have been avoided, and how the landscape has changed—if at all.

A reductive version of the complaints about American Dirt claims that the novel’s detractors believe that a white woman should not write about the experiences of Latino migrants. In truth, nearly all of the considered criticism of the novel points out either inaccuracies or stereotypes that, according to Myriam Gurba’s widely shared review on the site Tropics of Meta, betray Cummins’ lack of knowledge about her subject matter and attempt to render a complex situation and culture into “trauma porn” palatable to an American readership—a readership envisioned as primarily white.

“Most of the critical missteps were obviously done to head off that sort of criticism.”

Nevertheless, American Dirt arrived in reviewers’ hands embellished with endorsements from such revered Latina literary figures as Dominican American Julia Alvarez and Mexican American Sandra Cisneros, writers who either missed or weren’t bothered by the glaring flaws decried by Gurba. “Some of this is generational,” an assistant editor, who is white, told me. “I would have spoken up 100 percent about how the problematic the book was.” This is exactly the hypothetical situation that journalist George Packer imagined in a recent speech given while accepting the Hitchens Prize, later reprinted in the Atlantic: “If an editorial assistant points out that a line in a draft article will probably detonate an explosion on social media, what is her supervisor going to do—risk the blowup, or kill the sentence?” For Packer, that’s a dystopian scenario, but it might have saved Cummins’ publisher, Flatiron Books, a lot of grief.

Most publishers enlist the opinions of multiple in-house readers, particularly when launching a book that commands a large advance (reportedly seven figures in American Dirt’s case) and a correspondingly large marketing budget. As many of the industry’s critics have repeatedly pointed out, however, those employees are overwhelmingly white, although an editorial director of an imprint told me “over 50 it’s just white people who went to Harvard, but the pool of people under 35 is much more diverse.” Whether feedback from junior staff is heeded varies from house to house and editor to editor. Several of the outside observers I spoke with suspect that Flatiron, a relatively new imprint of Macmillan Publishers, anticipated that the mismatch between Cummins’ identity and that of the characters she depicts could attract negative attention; they just misjudged how much. “Most of the critical missteps” in the marketing of the book, said one editor, “were obviously done to head off that sort of criticism.”

These moves backfired spectacularly, among them an author’s note from Cummins expressing the wish that “someone slightly browner than me would write” a similar story and describing migrants as people who “we” tend to see as a “faceless brown mass.” These measures were “tin-eared at best,” in the words of one editor I spoke to, as was a bio noting that Cummins’ grandmother was Puerto Rican and referring to her Irish husband as an “undocumented immigrant.” A photo of a luncheon the publisher threw for Cummins last spring in which floral centerpieces mimicked the barbed wire in the book’s cover art further fanned the flames, as did a letter from Cummins’ editor, Amy Einhorn, included with advance reader copies, that characterized the issue of immigration as having only recently entered the “national zeitgeist.” Unlike the contents of a 400-page novel, these blunders could be easily circulated on social media. “It’s the perfect literary scandal,” one senior editor observed, “because you don’t even have to read the book.”

“Everyone saw this coming,” the editorial director told me, “but some people thought that the book’s politics were liberal enough that no one would attack it. They underestimated how the circular firing squad works.” He dismissed the notion that everyone at Flatiron was simply oblivious to the pitfalls of publishing American Dirt. “Look,” he said, “book publishers are 10 times more concerned with identity politics than Twitter suspects. This is a media company. The people who work here are the same people who are on Twitter.”

“You can’t be Twitter woke and Walmart ambitious.”

But the most common take on the American Dirt fiasco is that it resulted from Flatiron’s hubristic failure in what the industry refers to as “positioning”—that is, communicating the genre a house considers a new book to fit into. “From what I’ve heard,” said one senior editor, “it’s a really quick, pacey, dramatic read, and there’s a whole coterie of people who will say that to their friends, and word of mouth will move across the country like wildfire.” In other words, the novel is a work of commercial fiction, much like Where the Crawdads Sing and other titles that sell in large numbers while generally flying under the radar of cultural critics and political commentators. Where Cummins’ publisher went wrong, in this formulation, was to present American Dirt as if it was also, in the senior editor’s words, “a contribution to a vital understanding of this issue,” with the implied claim of representing the issue accurately rather than using it as a backdrop for an entertaining suspense story. “It’s a commercial book that was mispositioned as literary,” another senior publishing executive observed. Flatiron’s publisher, Bob Miller, essentially acknowledged this in a statement released Wednesday, noting, “We should never have claimed that it was a novel that defined the migrant experience.” This set American Dirt up for a degree of scrutiny to which most popular bestsellers are not subjected, at least not right out of the gate. “You can’t be Twitter woke and Walmart ambitious,” the assistant editor quipped.

By comparison, The Help, a 2009 novel by Kathryn Stockett (also, as it happens, edited by Einhorn) was as heavily promoted to the mainstream market as American Dirt was, but without the same appeal to reviewers in major publications—or claims that it addressed a serious issue on serious terms. (Instead of barbed wire, the cover art features, inexplicably, a genteel painting of three perched birds against a golden backdrop.) Only after the book had sold millions of copies and attracted the attention of filmmakers did it draw high-profile criticisms for its depiction of race relations in the South during the 1960s. To cite a more recent example, Don Winslow, who also blurbed American Dirt, is a white author who writes bestselling thrillers about Latin American drug cartels in which the characters are arguably just as much stock figures as those in Cummins’ novel, yet his work is not presented as social commentary, with all the heightened attention such pretenses bring with them. While such distinctions may seem arcane, Gurba herself, in a recent interview with the radio program Latino USA, stated that she would have found American Dirt less offensive if its publisher had marketed it as “a romance thriller,” rather than “promoting it as if it was a novel of political protest.” She would have much more respect for Cummins, Gurba went on, “if she owned who she is and what she’s writing.”

No one I spoke to expected the controversy over American Dirt to harm the novel’s commercial prospects. “The consumers don’t care. They. Don’t. Care,” said one editor with exasperation. “If it does register, they’ll just write it off as PC.” While one source said he was sure the incident is “humiliating” to Cummins, her publisher, and other people associated with the book, “you can wipe your tears away with money.” A petition posted to the site LitHub and signed by more than 130 writers asking that Oprah Winfrey “reconsider” selecting American Dirt for her book club might have an effect if Winfrey complies, but the editorial director insists that even this could end up helping the title. “The challenge in publishing books is making sure people have heard of them,” another editor explained. “What people will know is that this is a book other people are talking about.”

Amy Einhorn, the editor who acquired American Dirt.

Photo by Bob Krasner.

Independent bookstores are likely to suffer the most as the result of the current uprising against American Dirt. On Wednesday, Flatiron announced the cancellation of Cummins’ book tour, citing threats. Some observers have questioned the reality of such threats, but a spokesperson for Flatiron showed me emails the publisher had received from booksellers, one of which reported that a potential speaker had received physical threats and others explaining that they could not guarantee Cummins’ safety. “Small booksellers don’t have the resources to hire security personnel,” one editor explained to me, “and many of them were counting on the income from a big bestseller this spring.” Now Amazon or a big box store could get those sales instead. Neither Cummins (who sold a second book to Einhorn, reportedly also for a seven-figure advance, shortly before Einhorn left Flatiron to become president of fellow Macmillan imprint Henry Holt) nor Flatiron itself is likely to take as much of a hit. “So her tour was cancelled,” an editor noted. “Do people know what a shitshow a book tour is? They’re so arduous!” (Flatiron has announced plans for a series of “town hall” meetings with Cummins to discuss the book publicly, but no specifics have been released.)

Could adult trade publishing adopt a practice common in the young adult sector and enlist sensitivity readers to screen books for their authenticity in depicting marginalized identities? No one seems to regard that as likely, although one editor did say that she hoped to see “in-house talent at publishers acknowledging their own limits and using their powers to consult with outside experts” when needed. And while some people bristle at the very suggestion of using such readers, another editor noted that consultations are far from unprecedented. “If you set a novel in ancient Rome and you decide that you want a professor of classics to read through it, no one would be shouting about free expression.”

The controversy over American Dirt may, however, make publishers more cautious. “I don’t see this leading to a decision not to acquire a book that we would have acquired in the past at all,” said one publisher. “But I do think that in cases where there’s a mismatch between the identity of the character and author, the value of those books over books where the author is a member of the community being written about will be more closely scrutinized. There’s a fine line between free expression—which can mean publishing books that not everyone on the staff likes—and publishing responsibly, ethically, and with proper due diligence.”

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2vHaq19

via IFTTT

Jon Favreau’s The Wilderness

Listen & Subscribe

Choose your preferred player:

Get Your Slate Plus Feed

Copy your ad-free feed link below to load into your player:

Episode Notes

On the Gist, Bloomberg will join the debate stage.

In the interview, Crooked Media’s Jon Favreau is here to talk about the new season of his series The Wilderness, where he goes to different parts of the country and explores politic tastes with focus groups. He and Mike discuss the four types of voters he targeted, what people want from a Democratic candidate, and the importance of the upcoming election.

In the spiel, landmines and military.

Email us at thegist@slate.com

Podcast production by Daniel Schroeder and Priscilla Alabi.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2UgcZBA

via IFTTT

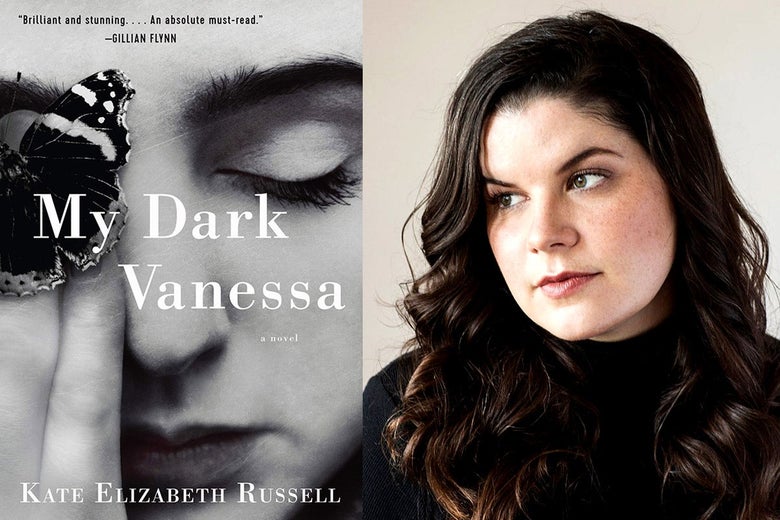

Why My Dark Vanessa Is the New Book Everyone’s Angry About

Photo illustration by Slate. Images by HarperCollins and Elena Seibert.

Another day, another literary scandal involving a seven-figure book deal. Even as details are still emerging in the maelstrom around Jeanine Cummins’ migrant novel American Dirt, there’s already a new Literary Twitter drama brewing, this one concerning Kate Elizabeth Russell’s much-anticipated debut My Dark Vanessa.

My Dark Vanessa, which revolves around the relationship between a teenage girl and her teacher, has drawn praise from the likes of Stephen King, Gillian Flynn, and Kristen Roupenian, author of “Cat Person.” But the book is now embroiled in a controversy similar to the one around American Dirt. Wendy C. Ortiz wrote an essay accusing Russell of borrowing from the real-life experiences of a Latina author—in this case, those in Ortiz’s memoir Excavation—for her own work of fiction. The parallels between the two books are being used as evidence of the entrenched biases and double standards of the publishing industry. Others, though, say that Ortiz’s accusations of plagiarism are hasty and misguided. Here’s what’s going on.

The BookMy Dark Vanessa alternates between the past and present of titular character Vanessa Wye. Vanessa’s present is like ours: In the midst of the national reckoning around sexual assault and abuse brought on by the #MeToo movement, she is re-evaluating a relationship she had when she was 15 with her 42-year-old English teacher Jacob Strane. In 2017, Strane is accused of sexual abuse by another former student, who reaches out to Vanessa. As the publisher summarizes it: “Now Vanessa suddenly finds herself facing an impossible choice: remain silent, firm in the belief that her teenage self willingly engaged in this relationship, or redefine herself and the events of her past. But how can Vanessa reject her first love, the man who fundamentally transformed her and has been a persistent presence in her life? Is it possible that the man she loved as a teenager—and who professed to worship only her—may be far different from what she has always believed?”

My Dark Vanessa was included on both the New York Times’ and the Guardian’s most anticipated books of 2020, with the latter likening it to “an inversion of Lolita for the #MeToo generation.” In interviews, Russell has said that she’s been working on the book since she was 16 and that the project began as a memoir, with the character of Vanessa based on Russell herself. She says the character of Strane, however, was always intended as a composite of older men that Russell was involved with as teenager. “I knew what was at stake for them, didn’t want to betray them—but now I see it as an empowering decision for me both as a woman and a writer,” she told Entertainment Weekly. “Fiction gave me the freedom to center my own emotional experience rather than focus on the details of what exactly an older, powerful man did or didn’t do to me.”

The Other BookOn Wednesday, Ortiz published an essay in Roxane Gay’s Medium publication Gay Magazine about the trials that she faced in securing a literary agent and selling Excavation, which primarily deals with “her relationship with a charming and deeply flawed private school teacher fifteen years her senior.” She begins the essay by explicitly comparing the situation to American Dirt, then writes that “a white woman has written a book that fictionalizes a story many people have survived and the book is receiving tremendous backing and promotion. The book this time, though, is titled My Dark Vanessa. The book I wrote, Excavation, is a memoir with eerie story similarities, and was published by a small press in 2014.”

The bulk of Ortiz’s essay deals with her encounters with white literary gatekeepers who assure her that her writing is “powerful” and “striking,” that her memoir is “powerful and complex” and that “her story should absolutely be heard,” but then also tell her that there’s no room in the market for her memoir, which is at once too original and too similar to other memoirs to make it worth buying. Ortiz eventually published Excavation with a small press, went on a self-planned book tour, and, a year later, put her book up for auction to be reprinted with a big publisher, only to be met “with radio silence.” When she learned of My Dark Vanessa from an online summary, “it sounded so much like Excavation I thought I was going to pass out.”

Ortiz admits that in her essay that she has not read Russell’s book, nor does she intend to, writing on Twitter that she is “uninterested in reading a book that sounds like a fictional take on a reality she lived.” Soon after Ortiz mentioned on Twitter that she was “‘looking forward’ to the book that sounds like [hers] coming out in March,” she says Russell reached out to her.

The ControversyApparently it had come to her attention that people were comparing the books and were upset. She confirmed that she had read Excavation in 2015, and offered a number of other influences in the writing of her novel. I dealt with this email the way I deal with things I don’t need in my life: I put it in a folder and decided I didn’t need to look at it further. Before I did that, I forwarded it to two other trusted people, to make sure my rage was proportionate. The consensus was that there were suddenly an awful lot of justifications, a little too late. The questions I have about it go unanswered.

Ortiz’s account of her experiences with the publishing industry, which is 76 percent white and difficult for writers of color to break into, has struck a chord, especially on the heels of American Dirt.

Still, some are alarmed by the backlash against Russell, saying that Ortiz’s fans are, in an over-zealous attempt to critique the insular forces of the publishing industry, demanding that Russell out herself as a survivor of sexual abuse to prove that she didn’t plagiarize an experience that is unfortunately very common. Russell did list Ortiz’s memoir as a component of her research—along with more than 50 other works of fiction, film, and poetry, including 14 other memoirs. While there’s no telling at this point how the situation might resolve, what is abundantly clear from both the discourse around American Dirt and My Dark Vanessa is that the publishing industry is long overdue for a reckoning of its own.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3b1kBha

via IFTTT

What Are the Democratic Candidates’ Climate Proposals for Black America?

Hurricane Dorian floodwaters in Georgetown, South Carolina, on Sept. 5, 2019.

Sean Rayford/Getty Images

Miles of shoreline that once protected and nourished the Gullah-Geechee are eroding, subjected to harsh storms that have damaged the delicate coastal ecosystem of South Carolina’s Sea Islands. In 2018, when Hurricane Florence caused flooding in Cheraw, contaminated soil containing elevated levels of cancer-causing PCBs from an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site flushed into people’s homes. Bacteria-rich pluff mud that makes up the state’s saltwater marshes could potentially aid in the cleanup, but the marsh grass is waning, and it can’t hold the soil in place. So it washes away.

It’s a straightforward statement of fact that climate change is among the biggest imminent threats to humankind—and Black communities such as those in South Carolina are going to take a disproportionate hit. Contamination, sweltering days, and rising sea levels that drown out the low country are among the issues that have made South Carolina “somewhat of a hot spot in terms of environmental issues,” said Brenda Murphy, the president of the state’s chapter of the NAACP.

South Carolina, like other states in the Southeast, has warmed at a less accelerated rate than other parts of the U.S., according to an August 2016 EPA pamphlet. But as global temperatures continue to rise, South Carolina is likely to experience unstable crop yields, livestock damage, more powerful tropical storms, increased inland flooding, a jump in uncomfortably hot days, and a subsequent increase in the risk of heat-related illnesses.

Democratic candidates have made it a point to include climate change and issues of environmental justice in their policy platforms. The party has had a difficult time engaging with voters on the issue in previous cycles, but this go-around there have been more specific efforts to elevate the topic nationally.

With the South Carolina primary approaching, though, Slate wanted to find out how the candidates are drawing the connection between the Black voters—particularly those in rural areas—they want to reach and the subject of climate change. I asked all 11 Democratic campaigns what they were doing to discuss climate change with Black voters and how they might be personalizing the issue for folks who, for example, may notice that it’s hotter outside or that a food item they like is regularly out of stock, but don’t necessarily link it to climate change or environmental injustice.

Eight campaigns responded (we’ll add more if they reply). Few of them had a specific, tailored effort to address how climate change and environmental injustice affects Black communities in particular and how to engage with them on the subject. Often they presented their work in both the climate sector and racial justice while noting that the two do indeed overlap. Or they mentioned the disparate impact on Black communities in the climate plan, while the policy proposals themselves remained overarching, with nothing as targeted as, say, Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s education plan to pour much-needed funding into historically Black colleges and universities.

But a more nuanced connection could lead to a better understanding of how Black Americans are being affected and will be critical to any campaign initiative to adequately shape policy. The language used and how the issue is perceived is different within Black rural communities, according to Cliff Albright, a co-founder of Black Voters Matter. A change in monthly expenses, such as a utility bill, or the increased frequency and disastrous impact of the past couple of hurricane seasons is how many people notice climate change.

“If you just ask about climate change, you may not get much of a response—which doesn’t mean that we don’t care about climate change,” said Albright. “It just means our entry point is different.”

Michael Bennet“America’s Climate Change Plan” was the first policy platform Bennet released upon launching his campaign, a campaign spokesperson said. It calls for the creation of an Office of Climate and Environmental Justice at the EPA and says a Bennet presidency plans to “reorient the organization and mission of the Department of Health and Human Services” as part of a plan to focus on public health, “especially for vulnerable populations.”

The plan emphasizes the need for a “Climate Bank,” which would allot $10 trillion toward fighting climate change while focusing on communities affected heavily by pollution. Two bullet points, about job creation and building an EPA climate office, likewise mention helping communities that have borne the brunt of environmental harm. But there is no specific mention of Black people, or any community of color for that matter.

Bennet traveled to Gulfport, Mississippi, in July, where he met with NAACP Climate Chair Kathy Egland and Ruth Story, the former Gulfport branch president of the NAACP. During that same visit, Bennet met with a group of crabbers and discussed climate change’s impact on local fisheries.

Joe Biden“Vice President Biden knows people of color in rural communities across America are more likely to live in areas most vulnerable to flooding and other climate change–related weather events,” said Jamal Brown, the national press secretary for the Biden campaign.

A piece of Biden’s climate plan states how Black Americans are uniquely affected by climate change. Overall, the plan “holds polluters accountable for the damage they’ve caused, particularly in low-income communities and communities of color, not only due to climate change but the pollution they are pumping into the air that is breathed and into the water that is drunk in those communities,” said Brown. “And it ensures that communities across the country including Flint, Michigan, and Denmark, South Carolina, have access to clean, safe drinking water.”

The campaign also pointed to Biden’s rural plan as well as his health care plan to expand Medicaid in rural red states.

Michael Bloomberg“Environmental justice must be at the heart of our climate work,” said a campaign spokesperson. “The burden of climate change and pollution too often falls heaviest on low-income and minority communities. As president, Mike will focus federal investments in communities disproportionately impacted by climate pollution.”

Bloomberg recently announced the Greenwood Initiative, focused on economic justice for Black America; it does have one mention of environmental justice. The campaign also released a climate change policy agenda, which includes details about investment in vulnerable communities. A bullet point within the climate change resilience portion of the plan mentions the disparate impact climate change has on Black Americans. Communities of color are mentioned once more in terms of outcomes in his clean transportation plank.

Bloomberg’s campaign said that, in addition to listening to voter concerns on the matter, it has also briefed a number of environmental justice organizations, including the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network and the Greater New Orleans Foundation, on its policy plans.

Pete ButtigiegThe Buttigieg campaign has hosted several roundtables in rural South Carolina, including one in Denmark, where conversations regarding environmental justice were featured.

“Climate change is the greatest threat of our time, and often low-income, Black Americans are hit first and hardest,” wrote a spokesperson for the former mayor. “That is why our campaign has made addressing climate change a priority—whether it’s holding pollsters accountable, ensuring Black neighborhoods have the infrastructure and resilience they need to survive and thrive after climate disaster or ensuring our public health systems are equipped to support their needs.”

The spokesperson wrote that Buttigieg’s plan focuses on “gaps in our public health systems and infrastructure that disproportionately affect communities of color and the poor.” The Buttigieg climate plan has a few mentions of Black Americans and the disparate impact. It also mentions “deploy[ing] community-centric resources”—such as sending federal assets to assist during natural disasters—to help communities.

Buttigieg’s “Douglass Plan” offers a bit more nuance into policies that would help Black Americans suffering environmental injustice specifically—including a push to remove lead paint from old houses and the creation of a public health data system.

Amy KlobucharThe Minnesota senator’s campaign pointed Slate to her climate plan, which notes that she would “prioritize assisting [communities of color] as they adapt to the effects of climate change” and make sure they are included within any policy decision making.

Her plan also promises to strengthen the EPA, the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, all of which play a role in mitigating the direct and indirect effects felt by communities.

Deval PatrickDeshundra Jefferson, a spokesperson for the former Massachusetts governor, said Patrick’s campaign is talking to voters everywhere about the issue of climate change, including those in communities like Round O, South Carolina.

“Rural communities often see and feel the impact first. When we address climate change, we are keeping our most vulnerable communities at the top of mind,” said Jefferson.

Patrick’s climate plan doesn’t have any specific mention of Black people or any community of color, but it does note that “the greatest impact has been and will continue to be on some of the most vulnerable people in the United States and abroad.” The former governor would also seek to bolster EPA cleanup efforts in “communities that have been underserved.” His opportunity agenda mentions that he will make various investments in rural communities.

Bernie SandersThe Sanders campaign provided several examples of how the Vermont senator is reaching Black rural voters, including his tour of South Carolina’s low country, an area that has been affected by the increased frequency and severity of storms; a climate-focused town hall in Myrtle Beach; an environmental justice town hall in Denmark; and breakfast in Georgetown. Sanders has also visited Williamsburg County, where he toured a local hospital that was closed due to damage sustained in the 2015 thousand-year flood.

Surrogates, according to the campaign, also regularly address climate change when engaging with Black communities.

“Personal storytelling is a huge part of our organizing program, and we’ve done a lot of training with our volunteers on how to have personal and [persuasive] conversations with people they know and with people they don’t know,” said national constituency organizing director Yong Jung Cho.

“Our supporters use their personal stories when they volunteer with our campaign—and study after study shows that it’s one of the best tools of persuasion,” she added.

And, of course, the campaign pointed to Sander’s Green New Deal, which puts forth a number of policy proposals and federal regulations that seek to address the disparate impact Black Americans face in the climate crisis.

Tom SteyerSteyer’s plan for climate justice mentions that though “climate change affects us all, it hurts low income communities and communities of color first and worst. The interconnected problems of poverty, systemic racism, and pollution demand urgent solutions.” There is no specific mention of Black Americans.

Axel Adams, the Steyer campaign’s director for African American outreach, explained the ground game in Black communities in an interview with Slate. He said the team engages with voters in meetings at churches and also reaches out to officials and activists. Often campaign staffers talk to folks who aren’t certain that what they’re experiencing is related to climate change, but they do notice changes in weather patterns or food shortages. “They don’t tie it to the ecosystem,” said Adams. “When you explain that to them … they pay more attention to it.”

The same goes for environmental justice: “They know something is happening. A lot of times they know the people in their community are sick—a high rate of asthma, a higher rate of cancers. And they may assume that something is going on in that area, but they don’t know what it is.”

Adams said the Steyer campaign explains that the issues people are noticing could be associated with climate change or environmental injustice. The campaign makes the connection by pointing out food shortages or how certain crops like peaches aren’t growing as great as they once did.

“We make it relative and real,” said Adams.

Slate is covering the election issues that matter to you. Support our work with a Slate Plus membership. You’ll also get a suite of great benefits.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/36I3vSd

via IFTTT

The Weinstein Trial Isn’t the First High-Profile Case to Feature a Graphic Description of the Defendant’s Genitals

Harvey Weinstein.

David Dee Delgado/Getty Images

In a New York City courtroom on Friday, former actor Jessica Mann—who alleges that Harvey Weinstein raped and sexually assaulted her on multiple occasions in 2013—gave detailed descriptions of his body and genitals, claiming that he “smelled like shit” and “had a lot of blackheads” on his back. But it was this testimony that drew the most attention: “The first time I saw him fully naked, I thought he was deformed and intersex. He has an extreme scarring that I didn’t know, maybe [he] was a burn victim,” she said. Mann also alleged that Weinstein “does not have testicles, and it appears that he has a vagina.”

Graphic descriptions of genitals have played roles in several other high-profile allegations of sexual abuse and harassment. They’re usually introduced in an attempt to corroborate the alleged victim’s claim that he or she has seen the genitals of the accused. During one 2009 deposition, Jeffrey Epstein was asked whether his penis was “egg-shaped,” as one accuser had said. In 1993, when the Los Angeles Police Department was looking into allegations that Michael Jackson had sexually abused 13-year-old Jordan Chandler, investigators had Chandler draw a picture of Jackson’s penis. Jackson had vitiligo, a skin condition that causes discoloration, and Chandler’s drawing included some distinctive markings. Later that year, police forced Jackson to undress and took photos of his penis, prompting Jackson to deliver a televised denial of the allegations, in which he called the strip search “the most humiliating ordeal of my life, one that no person should ever have to suffer.” Though police found that Chandler’s drawing was accurate, prosecutors dropped the charges against Jackson when Chandler stopped cooperating.

In 1994, Jackson settled a civil suit filed by Chandler for $23 million. That same year, Paula Jones filed a legal complaint alleging that Bill Clinton had exposed himself to her, fondled himself in front of her, and asked her to “kiss” his penis. “There were distinguishing characteristics in Clinton’s genital area that were obvious to Jones,” the claim said. A judge barred Jones from explaining those characteristics before her case went to trial (which it never did). Still, Jones’ team put forth that claim of “distinguishing characteristics” as proof that Clinton had shown her his penis.

In response, Clinton’s personal lawyer obtained sworn statements from multiple doctors that refuted the existence of any abnormalities, then delivered one of the most indelible lines of Clinton’s presidency. “In terms of size, shape, direction, whatever the devious mind wants to concoct, the president is a normal man,” the lawyer said. “There are no blemishes, there are no moles, there are no growths.”

It later came out that Jones wasn’t referring to a skin condition, but to the suggestion that Clinton’s penis tilted at an angle. (Meanwhile, Monica Lewinsky—though she didn’t want to go into any details herself—allegedly disagreed with Jones’ assessment during conversations with prosecutors before she appeared before Ken Starr’s grand jury.) Jones’ first lawyer said Jones had never mentioned any “distinguishing characteristics” to him—that it wasn’t until she changed legal teams that she made that particular claim—which some have used to argue that Jones invented or embellished her story.

It’s not entirely clear why Mann decided to include a description of Weinstein’s body and genitals in her testimony. Weinstein’s defense team isn’t trying to prove that these women never saw his genitals, or that they’re fabricating the sexual encounters. His attorneys are arguing that they happened, but that they were consensual. Weinstein attorney Donna Rotunno has characterized the encounters as “regret sex.” “I think it’s easy to look back and say, ‘Oh, you know, maybe I didn’t love that experience,’” she told Vanity Fair. She said the women who are accusing Weinstein were “using” him by implicitly trading sex for career advancement: “They didn’t look at Harvey and say, ‘Oh my god, he’s the most gorgeous guy I’ve ever seen and I want to go to his hotel room.’ They looked at Harvey and said, ‘Harvey can do something for me.’”

Even if Mann’s account of Weinstein’s genitals is accurate, Rotunno can still argue that what Mann calls rape was actually consensual sex that Mann came to regret. Mann may be trying to elicit feelings of repulsion from the jury to bias them against Weinstein or sow disbelief that a beautiful woman in her 20s would elect to have consensual sex with a man whose body meets the description she offered in court. But Rotunno seems to have anticipated Mann’s evident disgust with Weinstein’s body, too, by portraying the sex as transactional.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2OihVSr

via IFTTT

Which Republicans Had the Worst Excuses for Ending the Impeachment Trial With No Witnesses?

The man the president knows as “Lil’ Marco.”

Mario Tama/Getty Images

As Donald Trump’s impeachment trial drew towards a close on Friday with a 51-49 vote against the Senate hearing from witnesses or seeking documents, Republican Senators were coming out of the woodwork to explain why they’d refused to try to obtain any new evidence. Ultimately, only Sens. Susan Collins and Mitt Romney broke party lines to vote with the 47 members of the Democratic caucus in favor of calling witnesses.

This will be the first Senate impeachment trial in American history without witnesses called, and opinon polls show broad public support for witnesses, so the Republican decision to cut the proceedings short would seem to be hard to defend.

Still, these Senators tried their best! Here are the five most pathetic excuses Republican senators have offered to avoid calling witnesses according to cravenness.

5. Sen. Cory Gardner of Colorado

Gardner, who is up for re-election in Colorado this Fall, came out against witnesses already on Wednesday. His statement to Colorado Politics was:

I do not believe we need to hear from an 18th witness. I have approached every aspect of this grave constitutional duty with the respect and attention required by law, and have reached this decision after carefully weighing the House managers and defense arguments and closely reviewing the evidence from the House, which included well over 100 hours of testimony from 17 witnesses.

While this statement doesn’t appear too craven, you have to recall that Gardner represents a state with the greatest opposition to Trump of almost any represented by a Republican in the Senate and that his coming out early against witnesses helped Majority Leader Mitch McConnell close ranks on the subject. Framing the question as whether to go from 17 witnesses to 18—rather than whether to go from zero to one—neatly captures the Senate’s majority’s decision to pretend it was the House’s job to gather all the facts, and that they were helpless to try to learn anything more on their own.

4. Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida

Rubio, who was dubbed “Lil’ Marco” by the president the Florida senator now seeks to exonerate, released a video and issued a lengthy blog post on Friday explaining his decision. That statement read:

[N]ew witnesses that would testify to the truth of the allegations are not needed for my threshold analysis, which already assumed that all the allegations made are true.

And from the video:

Removing the president would in my opinion inflict extraordinary trauma on our nation, which is already deeply divided and polarized. Half the country would view his removal as nothing less than a coup d’etat and I ask you what scheme could Vladimir Putin come up with that would divide us more than that removal would. So I’m not going to vote in favor of tearing this country apart any further, or fueling a raging fire that already threatens our country.

The intense strings soundtrack accompanying the video pairs perfectly with the melodramatic and cynical message that to save the country from election interference, you must allow election interference.

3. Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee

Alexander’s message on Thursday night that he was voting against witnesses was noteworthy because he had been considered a plausible swing vote in favor of witnesses, and because of the implausible reason he offered for refusing to swing. Trump, he explained, was guilty of what the House managers had charged him with, and so no more information was needed. What they charged, though, “does not meet the United States Constitution’s high bar for an impeachable offense.” While Alexander finds Trump’s conduct to be “inappropriate,” he told NPR on Friday that he will still support the president in November’s election.

2. Sen. Ben Sasse of Nebraska

Sasse fashioned his career in the Senate, as Slate’s Ben Mathis-Lilley described it, as a “performatively deep thinker, an advocate of public decency.” What does the man who wrote a book titled The Vanishing American Adult think of Trump’s conduct in the Ukraine affair and whether or not witnesses should be called in his Senate trial? “Let me be clear; Lamar speaks for lots and lots of us,” Sasse told CNN’s Manu Raju, doing the presumably adult thing of deferring his reasoning for the most important decision of his public life to someone else. Even there, the straight-talking champion of integrity wouldn’t take the risk of repeating those words with his own mouth. “I asked if he believes then that Trump acted inappropriately,” Raju reported. “Sasse didn’t answer.”

1. Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska

Murkowski put to rest on Friday any questions about whether Chief Justice John Roberts might have to decide to break a 50-50 tie in favor of witnesses, or—by declining to vote at all—against them. Murkowski framed her vote as a brave one to protect the chief justice from a Democratic effort to “drag the Supreme Court into the fray, while attacking the Chief Justice.” She continued: “I will not stand for nor support that effort. We have already degraded this institution for partisan political benefit, and I will not enable those who wish to pull down another.” By smearing her colleagues who sought to uncover the full truth of Trump’s misconduct as vicious partisans while casting herself as the hero, Murkowski presented the most self-serving possible justification for her cowardice of them all.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/36Kznpk

via IFTTT

Can Pete Buttigieg Find a Stable Place in the Middle of a Divided Iowa?

Pete Buttigieg finishes his appearance at a campaign event January 31, 2020 in Sioux City, Iowa.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

ANKENY, Iowa—Neither Joe Biden nor Bernie Sanders have a lot to say about Pete Buttigieg in the closing stretch of the Iowa caucuses, but Pete Buttigieg has plenty to say about them.

“I’ve seen Vice President Biden making the case that we cannot afford to take a risk on a new person now,” Buttigieg said at a sizable rally in Ankeny, a Des Moines suburb, on Thursday night. “I would argue that at a time like this, what you can’t afford to take a risk of is falling back on the familiar, because history has shown us we have to look to the future in order to win.”

And Bernie? No thanks, pal. “Senator Sanders is speaking to goals for America that I think we all share, [but] is nevertheless offering an approach that tells folks who are not sure about going all the way to one side that they don’t fit,” Buttigieg said.

By contrasting himself against the two leading candidates—one representing the centrist pole, the other the left—Buttigieg is positioning himself as the middle-ground candidate. While Sanders and Biden argue over their Iraq War votes or their records on Social Security, Buttigieg dismisses those disputes as bickering over questions from decades past that voters are tired of hearing about. His frequent references to setting aside “old” arguments and looking toward the “future” usefully remind likely caucus-goers that he, unlike the frontrunners, will not become an octogenarian early in his first term.

His sales pitch about being neither Biden nor Sanders has found a customer base. The question is whether that base is big enough to sustain a candidacy. Speaking to Buttigieg supporters in Iowa about previous candidates they’ve supported this cycle is like walking through a graveyard of candidates who failed to thrive in the “consensus” position between Biden and Sanders. Yvonne Welshhons, of Ankeny, told me that she was originally supportive of Beto O’Rourke, but he turned out to be a “flash in the pan.” Cindy Blay, from Ankeny, also had looked at Kamal Harris before committing to Buttigieg in September, as had Barbara Nelson, who also considered Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren but discounted the latter given her support for Medicare for All. (“That’s a hard one to swallow,” Nelson said.)

It’s hard to find and hold a stable preference in the middle ground. Michael Van Essen, from Mason City, has always considered Buttigieg his first choice—as a gay man, he said, he will feel “honored” to caucus “resolutely” for Buttigieg on Monday night—but his second choices have rotated between Harris, Booker, and Warren.

Harris, Booker, and O’Rourke all tried to occupy the middle, but couldn’t last long in the exposed turf between the trenches. Warren briefly seemed to have found her footing there early in the fall, before her rivals to the right used her Medicare for All position to shove her into the left camp. Warren is still around, even if her numbers are down, because there are plenty of left voters who want what the left is selling, not because she was able to keep moderate voters engaged. Similarly, moderates Biden and Klobuchar are there to serve the moderate voters who appreciate pragmatic accomplishments and the ability to win over lapsed Republicans.

How is Buttigieg still standing there in the perilous center of things? He isn’t, really.

Many of the Buttigieg supporters I spoke to had considered either Biden or Klobuchar, who remained at the forefront of their second-choice preferences. None of them were considering Sanders.

Francie and Howard Sonksen, of Mason City, who had leaned toward Biden until observing that the former vice-president was “past his prime” when they finally tuned into a debate, said they’d considered Sanders “too extreme” from the start. Van Essen said that he would vote for Sanders if he were the nominee, but “would rather not have to. Well, obviously I would rather not have to, I don’t want to at all.” These were voters who wanted one of the moderates to earn the nomination. And the member of the moderate lane they had landed on was Pete Buttigieg.

Buttigieg may be pitting himself against Sanders and Biden, but he’s doing it on different terms. With Sanders, his objection is that his platform goes “all the way to one side”; with Biden, his objection is that he’s too “familiar” a face. Buttigieg presents himself as an ideological alternative to Sanders, but his point of contrast with Biden is simply that the Democrats need a newer model, with less Washington baggage.

Buttigieg may have first gained attention with assertive positions on eliminating the Electoral College and expanding the Supreme Court, but by summer’s end he had unsubtly transformed himself into something of a Biden backup. It was Buttigieg who did the shoving when Elizabeth Warren was shoved out of the “consensus” position, joining Amy Klobuchar to press her on whether her Medicare for All plan would require tax increases during an October debate that, in retrospect, was the most (only?) significant debate of the cycle.

While Buttigieg claims that he’s reaching out to both the left and the right, his right arm is getting much more tired. In Mason City, and at other events he’s been doing around the state, he spoke about how pleased he was to see “future former Republicans” at his events who are “just ready to put this flavor of chaos behind us.” He is directly trying to win Iowa by expanding the caucus electorate to the right. Ankeny, where Biden held an event days earlier, is the ideal place to do so. In his 2016 run, Republican Sen. Marco Rubio ran a suburban-focused campaign that was internally dubbed the “Ankeny Strategy.” Other candidates, as the Washington Post reported at the time, “joked that it felt like Rubio was running to be mayor of the Des Moines suburb.”

It’s been surprising speaking to voters in Iowa (a small sample of them, sure) and hearing how well the “lanes” theory of primary electorates is holding up. Usually such high-pundit methodologies for analyzing the thoughts of real human beings expire the first time the thoughts of a real human being are probed. But I have yet to meet the usual “Yeah, I’m stuck between Bernie and John Delaney” types. The left-wing voters are choosing between the left-wing candidates, and the moderates are choosing between the moderates. Maybe Pete Buttigieg is the special Obama-esque figure he’s pitching himself as, who can heal divisions both within the party and the country. But there’s no question to which division he belongs.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/36Q424h

via IFTTT

BoJack Horseman Became TV’s Best Portrait of Addiction and Recovery

BoJack Horseman.

Netflix

This article contains spoilers for the final season of BoJack Horseman

From the beginning, BoJack was always drowning. Even though the BoJack Horseman credit sequence was tweaked from season to season, the coda remained the same. At the end of the day, BoJack stumbles, backwards and expressionless, into his pool. He sinks to the bottom as his friends gawk in wonder at his predicament. What initially seemed to be a comedic pratfall was actually a meditation on the universal struggle to change and grow.

As an addiction therapist, I have long been a fan of comedy as a delivery device for complex issues. There’s so much misconception, judgment, and shame surrounding mental health issues—especially addiction—in today’s society, and opening a discussion about those topics without deploying a heavy hand helps to break down preconceived notions. In 2014, BoJack debuted alongside CBS’s Mom and FX’s You’re the Worst, all of which used humor as way to encourage frank and honest discussions about mental health and addiction issues as a relatable part of the human condition. BoJack soon became the stealthiest Trojan (talking) horse of them all. As both a comedy and a cartoon—two formats that hadn’t generally tackled such topics before—the series made its mark as the most delightfully unexpected place to find connection, understanding, and catharsis on TV.

Over the course of six seasons, BoJack used animation to stretch the boundaries of reality and cram the screen with freeze-frame gags, but the medium also made it surprisingly easy for viewers to find themselves in the show’s characters. Instead of a human man at the center, there was BoJack, a talking, depressed horse, and the supreme weirdness of that contrast invited viewers to make personal connections to the series in ways that would prove to be both meaningful and lasting.

However, even though the series sympathized with psychic pain, it never let its characters—and, by extension, us—off the hook. Where most TV cartoons use giddy resets to undo dramatic plot twists (Homer doesn’t age; Kenny never stays dead), BoJack forced its characters to deal with the ongoing ramifications of their actions, in ways both large and small. In the first season, a drug-tripping BoJack set fire to an ottoman, and it stayed crispy until he replaced it. In Season 2, the stakes were raised when BoJack was caught in bed with the teenage daughter of an old crush. BoJack, and the show, seemed to have put that experience behind him, but it became a key part of the series’ final arc, in which decades’ worth of bad deeds finally catch up with him. Actions have consequences, even in cartoon form.

For six seasons, viewers witnessed BoJack flirt with real change, only to backpedal when it came time to truly confront the painful memories and experiences that fueled his maladaptive behaviors. In the first half of Season 6, which Netflix released last fall, BoJack finally seemed ready. He went to rehab, worked at making amends, and embarked on a new career as an acting teacher. But as he made his way back into the world in the show’s final eight episodes, BoJack made one of the cardinal sins of recovery. While he faithfully continued to attend 12-step meetings after he completed inpatient rehab, he neglected to fully contend with all his past traumas, both those that he had created for others and those foisted upon him in childhood by his damaged parents. “Acting,” he tells his students, “is about leaving everything behind and becoming something new.” But he was running from his past, not reckoning with it.

BoJack’s final season drives home the idea that recovery, like life, is an ongoing process in which the future is never quite clear

BoJack’s long-simmering traumas came to a head in the penultimate episode of the series, “The View From Halfway Down.” In a surreal sequence that plays like This is Your Life meets Intervention, he attends a dinner party at which all the guests are dead, and who have either wronged or been wronged by him. Eventually, it’s revealed that this deranged fever dream is BoJack’s version of life flashing before his eyes. While he was metaphorically drowning for so long, now he’s physically drowning. As BoJack floats, passed-out and nearing death in his own pool, a mishmash of memory and oxygen-starved hallucination brings all of his history to bear in a way that underscores his conflicting feelings of guilt, confusion, and sorrow.

It’s of note that BoJack doesn’t make a conscious decision to confront his past; it’s just as the former mentor he betrayed tells him, “your brain going through what it needs to go through.” A supervisor once told me that clients must rip out the roots of trauma, otherwise the weeds will continue to sprout and choke any progress a person is attempting to make. However, in my experience, often clients have set up barriers to prevent them from accessing their traumas, because they’re just too much, man. The only way they have survived is to compartmentalize and numb whenever the feelings got too big. And while this may seem to be an effective coping skill, it is also one that is not sustainable. The way out is painful, but it’s a different kind of pain. It’s an unfamiliar pain. Most choose to stick with the devil they know rather than confront the source of their continued substance abuse. Who can blame them? Change is hard.

Yet, within his rapidly darkening mind, forced to confront his demons, BoJack does indicate willingness to change. He expresses sincere regret about his damaged relationships with both Sarah Lynn and Herb Kazzaz, and he actually experiences a genuine connection with his father. (That the latter is also Secretariat “for some reason” doesn’t make the moment less touching.) BoJack Horseman illustrates that harboring unresolved trauma can be deadly and, in doing so, brings viewers to that dark yet somehow hopeful place that’s long been a hallmark of the series. As long as we’re breathing, meaningful change is always possible.

In contrast to the immersive trauma of “The View From Halfway Down”, the series finale, “Nice While It Lasted,” reunites BoJack with the four people who made the most impact on him during this transitional period of his life. In turn, he gets a chance to reconnect with Mr. Peanutbutter, Todd, Princess Carolyn, and Diane. And, shocker, they’re all processing their own issues as well. Change can’t happen in a bubble. We all help one another. The series works to drive that point home as BoJack shares a final emotional moment with each member of his support system.

Despite the horrific things he’s done, BoJack is not beyond redemption. He returns, time and time again, to Diane Nguyen, the woman who he first felt comfortable sharing his childhood trauma with. At times, Diane and BoJack have been each other’s worst enablers, but at other times they have connected in deep, personal ways. They share a complex relationship, and the end of the series concludes on a picture-perfect note, leaving us to contemplate the wide-open future. Will they stay friends? Will BoJack relapse? The emotional generosity of the series extends right up until that final, lovely, lingering moment. It’s one in which we can imprint our greatest hopes for these two characters, but also consider the potential pitfalls that may line the road ahead. In allowing viewers this latitude, the series drives home the idea that recovery, like life, is an ongoing process in which the future is never quite clear.

In reaching out so personally and daring to tell such raw, human stories, BoJack Horseman has generously provided years of much-needed catharsis for viewers around the globe. For that, I’d like to echo Diane’s words by saying: Thank you, BoJack. Thank you for choosing to tell this story, for seeing us, and for letting us know that it’s always possible to try for a better tomorrow.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/37MqAo2

via IFTTT

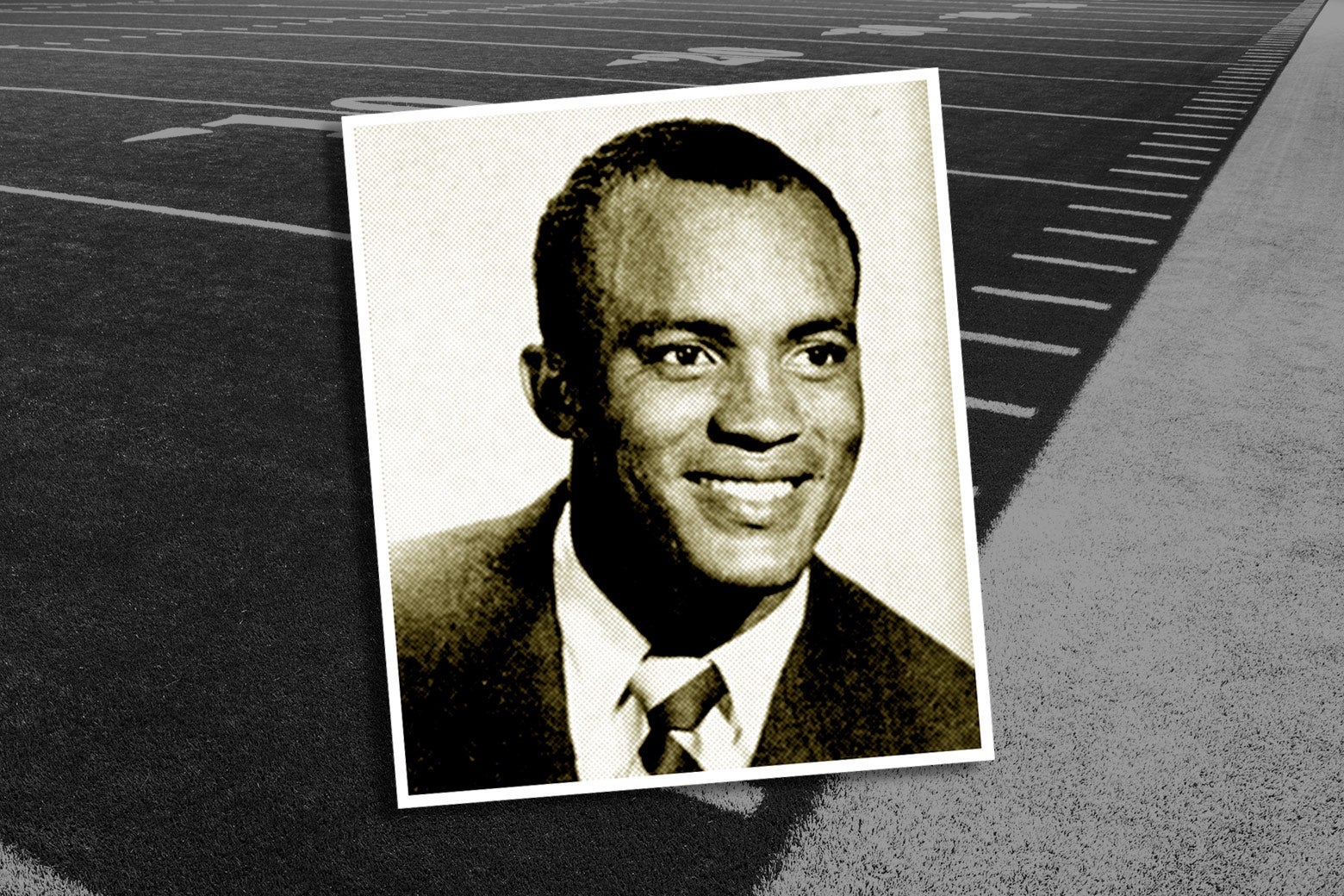

The Black-Owned NFL Franchise That Never Was

Rommie Loudd

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Wikimedia Commons and PhotoAlto/Sandro Di Carlo Darsa/Brand X Pictures via Getty Images Plus.

In September 1971, reporter Pat Horne of the Boston Record American had a big, back-page scoop. “EXCLUSIVE,” the headline blared. “Black Group to Petition NFL for Franchise as the ‘Memphis Kings.’ ”

The story was filled with remarkable details. The team would be located in Memphis, with “strong sentiment” to name it after Martin Luther King Jr., who had been slain in the city three years earlier. Sammy Davis Jr. and Sidney Poitier were involved. The group planned to solicit financial support for the estimated $12 million to $14 million expansion fee from the Martin Luther King Jr. Foundation and black-owned businesses, including Ebony magazine, Parks Sausage, and Johnson Products Co. It was even thinking about asking for help from President Richard Nixon, “who is an avid football fan.”

Top jobs would be filled by black NFL veterans. Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown and tight end John Mackey, the head of the league’s players’ union, were being considered for president. A list of potential coaches included Eddie Robinson of Grambling and Emlen Tunnell, a New York Giants assistant.

Cultivating the first black-owned team in pro sports, Horne wrote, would be “an incredible coup for the National Football League that prides itself in the total lack of racial problems within its ranks.” In the black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier, columnist Bill Nunn Jr. wrote, “How the whites would react to a black owned team remains questionable” but “[t]his dream of a black owned franchise is no longer a fantasy.” Another sportswriter predicted that black people across the country “will become avid rooters” and black players “will want to be traded to the new club.”

The NFL wasn’t as enthusiastic. The day after the Record American report, a league executive denied any knowledge of the effort. He said there was interest in Memphis to launch a franchise—the Boston Patriots and New York Jets had just played a preseason game there—but the NFL had no current plans to expand.

The Sept. 9, 1971, issue of the Boston American Record.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Boston American Record (screenshot).

Horne never followed up on his story—he left journalism not long after to become PR director for the Patriots—and the Memphis Kings disappeared from the news. But the idea of a black-owned team didn’t go away, thanks to a Patriots executive mentioned in Horne’s original article.

Rommie Loudd was an All-American tight end at UCLA in the 1950s who played professionally in Canada and later for the Patriots. He became the first black coach in the American Football League, with the Patriots, and then the team’s first black front-office executive. (The Patriots joined the NFL after the merger with the AFL in 1970. The team moved to Foxborough from Boston and changed its name to “New England” in 1971.)

In Horne’s article, Loudd wouldn’t confirm or deny knowledge of the plan, but he was almost certainly its source. A year later, in August 1972, the Tampa Tribune reported that Loudd and Jim Brown had met with officials in Orlando, Florida, about a black-owned team. Orlando officials were told, the paper said, “that Brown has demanded and gotten such a promise out of Commissioner Pete Rozelle and that it can be done.” The NFL denied that, too.

Loudd went public that winter, telling the Boston Globe that he planned to meet with Rozelle to pitch his plan for an Orlando team. “I know some people will call me a ‘nigger.’ But that won’t bother me. I know what I am and I know what I can do,” Loudd said. “Blacks have broken all kinds of barriers in sports. We’ve proven we can do the job in almost every area. This is the last step.”

His words seemed to have some impact. “We’re going to have to pace the problems of minority ownership,” Rozelle said before NFL ownership meetings a few months later. (Pace in this context almost certainly means “to set an example for” or “lead.”) “Forty percent of the players in the league are black,” the commissioner said. “Yet we have almost no blacks in front office positions. We will have to seriously consider that when we determine our expansion plans.” Rozelle said the league might need to practice “discrimination in reverse” to add minority ownership.

“Blacks have broken all kinds of barriers in sports. … This is the last step.” — Rommie Loudd

The idea of a black-owned NFL team came at a time when black athletes were “transitioning away from this activist model to a [financial] power model,” says Louis Moore, an associate professor of history at Grand Valley State University, whose tweet about the Memphis Kings on Martin Luther King Jr. Day led me to the story of Loudd. In 1966, Jim Brown formed the Negro Industrial and Economic Union (later renamed the Black Economic Union) to assist the growth of black-owned businesses. In 1970, Jackie Robinson was approached about the possibility of bringing a black-owned team to Major League Baseball. (Robinson wasn’t interested.)

But Loudd’s plan for a black-owned team in Orlando ran into obstacles. By mid-1973, his group was called the Florida Suns—not the Kings—and his investors were white businessmen. Loudd’s ambitions generated lots of local publicity, but he wasn’t able to negotiate a stadium plan. In February 1974, the NFL narrowed a list of 24 expansion candidates to five. Orlando didn’t make the cut. The league awarded teams to Tampa and Seattle.

Bill Clark, the sports editor of the Orlando Sentinel-Star, suspected that racial bias had blunted Loudd’s effort. Loudd persisted, though, immediately acquiring a team, the Florida Blazers, in the startup World Football League. The Blazers were a massive failure: They amassed more than $2 million in debts, bounced checks, missed player payroll, and were sued by partners and the league. One investor kicked the team out of its Holiday Inn offices. Loudd accused the city of overcharging for services and accused the community of racial discrimination. “If I’d been a white man, things here the past two years would have been somewhat different,” Loudd said. The Blazers lost to the Birmingham Americans in World Bowl I, 22–21.

Loudd was ousted as managing general partner of the team. But things would get much worse. Two days before Christmas, he was arrested on charges of embezzling state taxes from Blazers ticket sales. In March 1975, just before that trial was to begin, the Sentinel-Star splashed a headline across Page 1: “DOPE CHARGE ON LOUDD.” The paper described a “cocaine smuggling and sales ring that operated in at least three states.” It said the charges were the result of a six-month investigation that began with a probe of drug use by Blazers players. It said law enforcement officers feared that Loudd had been tipped off and had “fled to Zaire, in Africa.”

The March 10, 1975, issue of the Orlando Sentinel-Star.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Sentinel-Star (screenshot).

In a breathless follow-up story, the Sentinel-Star, quoting unidentified law enforcement agents, said the drug operation had outposts in Miami, Boston, New York, and the Bahamas. Loudd and his accomplices were “moving pounds of the stuff in lobster crates,” the paper alleged. The county sheriff’s department undercover agent who cracked the case was described as a “supernarc” engaged in a “cat-and-mouse game” with “the man”—Loudd, who had brokered the sale of a small amount of cocaine but promised much more. The story implied that Loudd could have had people killed.

The official case against Loudd was far less salacious. He was convicted of arranging the sale of 4 ounces of cocaine for $4,800 in Florida and a smaller amount of the drug in Boston. Loudd wasn’t present for the sales and never saw the money or the cocaine. Other charges, including the sales tax embezzlement, were dropped. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

In 1977, the Sentinel-Star reinvestigated the case and its own reporting and found both lacking. In a lengthy story in its Sunday magazine, the newspaper said it couldn’t prove Loudd was framed. But it quoted a Blazers investor saying an investigator told him, “We’re gonna get that black s.o.b. one way or another.” It also quoted from surveillance tapes showing the agent, posing as a businessman, telling a financially desperate Loudd that he and friends could invest up to $1 million in the team—and pressuring Loudd to get cocaine.

Loudd told the Sentinel-Star that he’d been entrapped. “He approached me—people must understand that—with the idea of investing [in the Florida Blazers]. And I end up with 14 years.” There were no promises of pounds of drugs, no international trafficking ring. “I tricked him, worse than I tricked anybody ever,” the agent told another officer on tape. The agent would later say that he meant he had outsmarted Loudd.

The Sentinel-Star admitted, tepidly, that it had regurgitated unsubstantiated police gossip. “The rather enthusiastic reporting of Loudd’s arrest appeared to contain some exaggerations, if not inaccuracies,” Sentinel-Star editor Jim Squires said in the magazine story about the case. In a separate column, Squires made a stronger point. If Loudd had been “a soft-spoken young white man, he could have bought and used four ounces of cocaine and no one would have cared,” he wrote. “But because Loudd was black, had a big mouth and made himself a ton of enemies he attracted the scrutiny others might have avoided.”