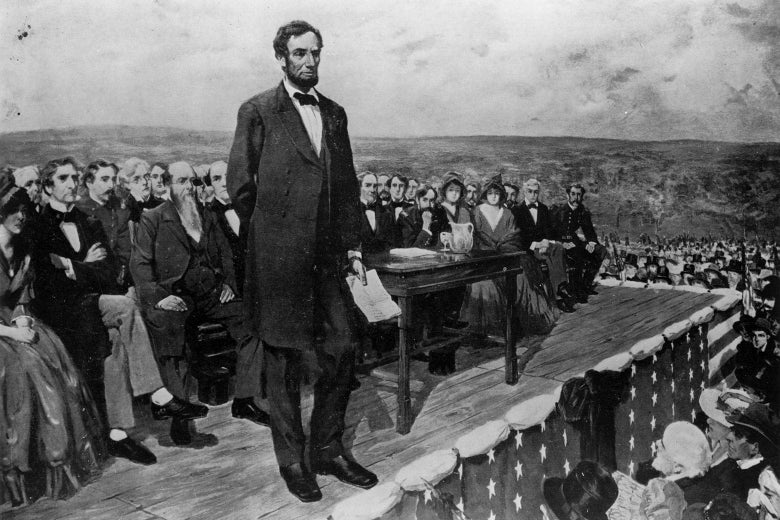

President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address on Nov. 19, 1863.

Painting by Fletcher C. Ransom. Photo by Library of Congress/Getty Images.

As he looked out over the Potomac in the autumn of 1863, President Abraham Lincoln must have been thinking about the tens of thousands of soldiers who, like the maple leaves along the river’s bank, had forever fallen to temper the American soil.

Against the backdrop of a wildly tumultuous year in American history, Lincoln took it upon himself to transform the language of American civic religion and mythology. Over just a few weeks, Lincoln offered two markedly different presidential declarations that forever changed this nation: his Gettysburg Address and the proclamation of a Thanksgiving holiday. The Gettysburg Address gave us the clarity of viewing our democratic government as a sacred institution of the people, by the people, for the people. Thanksgiving Day was to become our most revered secular holiday. Together, they represent the sacrifice and presence required to maintain our experiment in democracy.

The year 1863 had presented Lincoln with constant military, political, and moral battles, beginning on Jan. 1, when his Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, freeing all slaves in Confederate-held territory. The spring and summer brought Gettysburg and Vicksburg—important Union victories with a steep human cost. In August, Lincoln met with Frederick Douglass at the White House, an encounter often cited as a milestone on Lincoln’s path toward putting his political weight behind the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery. Shortly thereafter, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus, a controversial wartime measure.

It was in the wake of those nine relentless, eventful months that Lincoln, on Oct. 3, 1863, issued a proclamation of Thanksgiving to “set apart” the final Thursday in November. George Washington declared the first national Thanksgiving in 1789, but it didn’t take. By the time of Lincoln’s presidency, the holiday was often declared by Northern state governors for dates scattered throughout November and early December, making it something of an impromptu, regional custom. Lincoln, in a conversation with Secretary of State William Seward, suggested that a president “had as good a right to thank God as a Governor,” agreeing with Seward that the entire country ought to share the same Thanksgiving Day. The holiday would be “a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.” A little more God and a lot less football than we think of today, but nonetheless the birth of our beloved national holiday.

On Nov. 19, seven days before that national Thanksgiving was to be observed, Lincoln gave his Gettysburg Address before a Pennsylvania crowd of approximately 15,000. And so, sandwiched between the Thanksgiving proclamation and the actual Thanksgiving holiday, it is hard to look at the Gettysburg Address outside of the legacy of Thanksgiving. It is similarly near impossible to unpack the intended purpose of Thanksgiving without the context of Lincoln’s steady, moral leadership during a civil war.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address asked the country to recognize a rebirth of freedom and to engage in the process of realizing that freedom in the name of those who gave their lives for it at Gettysburg. It is an indelible articulation of American imagery and shorter than a tweetstorm at just 272 words. In it, Lincoln defines the United States of America as having been “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Lincoln’s rhetoric entrenches those opening words of the Declaration of Independence as the voice of the American spirit of liberty, above even the Constitution. Liberty is tied to “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” and it is not an entitlement. Rather, it is an “unfinished work” that the American people mustn’t take for granted, because it is constantly reborn by our own choices.

Lincoln was a conservative, a country lawyer by trade, and the first Republican president. And yet, by anchoring the American myth around the Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address stands in direct opposition to what we might today call constitutional originalism. Lincoln had throughout his career argued policy positions using words and acts from the Founders as a legitimate source of authority, but never as the only authority; his primary mode of argument was to find first principles underlying a legal or moral position.

Through Gettysburg and Thanksgiving, Lincoln offered a reverence for liberty—the equality of all men in the eyes of their creator—as that first principle on which to build American unity. A rebirth of freedom would come about by sanctifying a national mythology through shared words, deeds, and moments of pause.

With a national Thanksgiving, Lincoln created a secular sabbath, a day apart for the country to find gratitude and grace “in the midst of a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity.” In addition to giving us turkey trots and leftovers, Thanksgiving remains an annual reminder that quiet helps to clarify deeper purpose. This is particularly true when popular faith is tested and when we, too, find ourselves consumed by the tumult of the momentous events of our time.

Much like his words at Gettysburg, the conclusion to Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation rings prescient: that we “fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.” Amen.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2KQ1o6y

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言