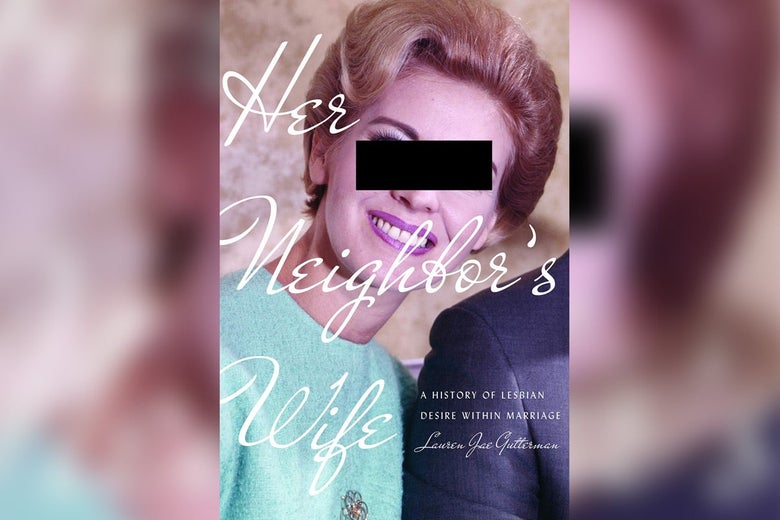

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via University of Pennsylvania Press.

The cover of Lauren Jae Gutterman’s new history of lesbian desire among married women in the postwar period, Her Neighbor’s Wife, features a woman in a robin’s-egg blue cashmere crew neck and perfect pink lipstick, her eyes blocked by a black box. From letters written to lesbian activists and from oral histories, Gutterman has collected 300 stories of wives who, between the end of World War II and the 1970s, found themselves falling in love with other women. This theme—those “perfect” postwar homes were actually seething with secrets!—has immediate appeal, but the actual history is full of sadness and, on occasion, tragedy.

Gutterman spoke with me recently about separate apartments, PTA meet-cutes, and divorcing husbands who turned mean. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rebecca Onion: I want to ask about the historical trajectory here. You write at one point that actually, in a counterintuitive way, it might have been easier in the 1950s to be a woman who experiences same-sex desire while in a heterosexual marriage than it was later on in the 1970s.

Lauren Jae Gutterman: Yes, for a few reasons. In the 1950s, there was just that tremendous expectation that women would marry and should marry; it was a cultural expectation and an economic imperative. Especially if women wanted to have children: to be able to support yourself and your children outside of marriage was really, really difficult. Not that marriage always provided economic security! But it was a better bet.

Then, once people were married, divorce was so stigmatized, husbands and wives had a shared desire and motivation to remain married.

And you know, understandings of marriage were very different in the late ’40s and ’50s and early ’60s than they became in the 1970s. So postwar marital experts routinely encouraged women to keep their emotional concerns to themselves, not to share those things with their husbands. They were supposed to maintain a calm, even front, and manage everyone’s daily lives, and not goes to him crying about inner emotional problems.

Then beyond that, a lot of husbands I found in this study were just kind of willing to turn a blind eye. They might have suspected their wives’ friendship [with a woman] was very close, but they weren’t going to pry into it. In some cases where husbands did have evidence that their wives had been or were actively involved in lesbian relationships, they thought it was something that would pass.

That’s another reason why, in the immediate postwar period, balancing the two lives was easier, because people weren’t really taught that lesbianism was a sustainable way to live a life. So it wasn’t an identity that would be a problem—it was an inclination that needed to be overcome.

And that was sort of how public and popular culture taught people to think about it, too.

Right, an example being midcentury pulp novels. In those, there’s always a lesbian who’s punished—or if there’s a married woman who engages in a lesbian relationship within marriage, in the vast majority of those stories she overcomes it and goes back to her husband.

I wonder what it’s like to write about a history that people find titillating. Like, I read the title of the book and thought, “Ooh, that’s interesting! Fifties housewives and their secret sex lives!” But people at the time were fascinated by it, too, which is part of your history—the pulp novels being one example of that fascination.

Yes! I do try and analyze that titillation in terms of pop culture representations, and to show that how the common storyline of a married woman engaging in a lesbian relationship, when it was presented for a broader audience, was a way that people tried to make these relationships unthreatening—that way, they might see them as titillating for an outside viewer, often a male onlooker.

When I was writing this history I found there weren’t very many women who were super sexually explicit in their letters or oral history interviews. … Most of them didn’t go into a lot of detail. A lot of lesbian history has been really consumed with this question: Did they actually have genital contact? Is that then how we’re going to define what counts, who counts as a lesbian or a queer woman, or a bisexual woman? Is this where we’re going to draw the parameters of our history?

For me, I really wanted to put that line of questioning to the side. Their desire was both sexual and romantic and emotional, and that was what most women talked about—they often talked about it in very romantic language.

Far from being titillated, I found I was unexpectedly saddened by this book. The stories of women who were stuck having to choose between being there for their kids and their true selves—though I’m not sure “true selves” is a way that people in the ’50s would have put it!—were so upsetting.

And the book also explores the sometimes quite negative way that women who were already out and living as lesbians perceived the married women who were still married to men—that they were clinging to their “insurance policies,” or too cowardly to stand up for themselves, or something. I wanted to be like, “Hey, leave them alone! They have kids!”

For me, one of my concerns in writing the book was not to replicate the activist perspective that these married women were simply closeted and self-hating—that they were kind of failed, politically. I wanted to really get at the difficulty of the situation that they were in. Especially when they had kids—but even when they didn’t have kids, many of them felt that they had been dishonest to their husbands, somehow, if they had known about their desires before marriage and gotten married anyway, and that it would be wrong to go back on a lifetime commitment and promise they had made. I think that that those are really hard questions, and so I didn’t want to simplify that. I wanted to be honest about the moral gray area that they were in.

In terms of the pressure on married women that was coming from lesbian activists who were already out, who had left marriages or had never been married … something I tried to show in the book was that this was a kind of pressure that increased over time. Among lesbian activists in the ’50s and early ’60s, there was a greater sympathy and understanding for the many women who experienced lesbian desires. They knew that it would be very difficult to build lives outside of marriage—or that many women didn’t realize this fact about themselves until they had married and made these commitments.

But by the ’70s, there was this new pressure from publicly out, lesbian feminist women who were saying, “No, you have to choose, and to remain married is a political failure. You’re failing to challenge social homophobia, and you’re actually harming other women, who are leading out lesbian lives outside of marriage.” Of course, I try to understand where those activist women are coming from as well!

“Part of avoiding divorce was that husbands and wives had to make marriage more flexible than we often think.”

Did you have any favorite stories in the book—in the sense of a story that you found very interesting, or telling, or helpful for articulating this history?

Maybe the life of the writer Alma Routsong, which I start the book with. It’s also a very painful story. I spent a lot of time looking through her letters and diaries in the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College. She did leave her marriage in the early ’60s, which was pretty uncommon, to live with her lesbian lover, and she decided to give up custody of the children to her husband. And that was something that she later came to regret, because he didn’t make it as easy for her to see the children or to have a relationship with them as she had thought he would. And so that was that was a sad story, although later in her life she did develop close relationships with her four daughters.

Or Barbara Kalish’s story, who fell in love with another PTA mom, Pearl, in California. After she left her marriage in 1970, she moved in behind a lesbian bar in Los Angeles.

Oh right! I remember that story … she got a small cottage back there, became an investor in the bar, and started leading her best life.

Right! And the oral history she gave had such funny details: She also started selling dildos, which she made out of electrical tape and mattress stuffing, at the bar. So that one had a happy ending.

In the epilogue, you mention something that struck me hard. You write that this history should inform the debate over gay marriage. “Limiting marriage to one man and one woman never truly assured the institution’s heterosexuality,” is how you argue it.

I wanted to make clear that when people idealized the 1950s stereotype of the idyllic, conventionally gendered, white middle-class marital ideal—it really was not what we think it was. Not only was there just widespread unhappiness in those relationships that we know about, particularly on women’s part, but those relationships really were not as straight as we think.

Part of avoiding divorce and making these marriages long-lasting was that husbands and wives had to make marriage more flexible than we often think about it being in that period, just to persist. And so there was a lot of dishonesty—if not fully lying to your partner, then a kind of recognition that “I’m not telling my husband or my wife the full truth, and they’re not telling me the full truth either.”

Another story that really struck me was from Mary Crawford, a woman who had a long relationship with a married woman named Muriel in Manhattan in the ’40s and ’50s. Mary was very much a part of Muriel’s life with her husband; Muriel would often stay over at Mary Crawford’s apartment, or spend her days there. Muriel’s husband would be gone some nights, supposedly “playing cards.” Mary said, “I don’t know what he was doing. Maybe he had a lover of his own; maybe it was a woman, maybe it was another man … ” They had a policy of not asking too many questions that enabled queerness and flexibility within marriage.

I have to stop myself from thinking “Well, that doesn’t sound so bad!” Because you make the point a couple of times throughout the book, that as a woman inside one of these marriages, you had to hope that if your relationship stops being OK with your husband, or if you try to make a break for it, he doesn’t turn into a jerk who uses everything against you. Because you found some of those stories.

Yes, some husbands would keep letters or evidence that their wives were engaging in lesbian relationships, or would just hold onto that knowledge of them, and use it against them in a custody battle or divorce.

I was thinking about the Katie Hill case from this year. So many people have talked about this case being particularly a millennial story—it’s about revenge porn, a polyamorous relationship, and female sexual fluidity or bisexuality. But it’s also a story of her estranged husband. He was accepting of her sexual relationship with another woman, for a while, so long as they remained married; then he used it against her as they became estranged. That’s a very common story, as far back as the postwar period. There are so many examples of husbands being accepting so long as they were married, then quickly shifting when the woman tries to leave.

I think that’s really important to include in there because otherwise the thing that you’re describing could sound pretty cozy: Everyone has their own secret apartment for their lover! But there’s still an asymmetry of power where the woman is on the short end, and the secrecy that’s protecting her could always end.

Yes. There were some husbands who were truly kind. I’m thinking of Pat Gandy, who wrote a letter to her husband, which he read one morning at breakfast. It said that she was a lesbian and needed to end the relationship. He stood up and gave her a hug and asked, “How can I support you?” And then he even continued to take care of her mother, who continued to live with him after Pat moved out, for many years afterward. A loving man.

Not all men! But still—far, far better to bet on a system where you have protection from the law!

Oh, without a doubt.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2XRX8bV

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言