Congress, really?

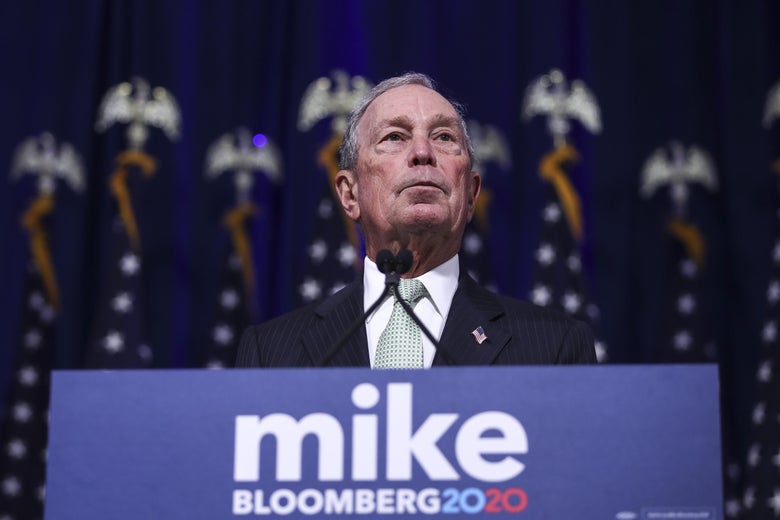

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Michael Bloomberg, who is now officially running for president, has always presented himself as a moderate, data-driven problem solver, a guy far less interested in ideology than numbers and results. To see how that image doesn’t always mesh with reality, though, it’s useful to revisit some of his more notorious comments about what brought on the Great Recession.

One morning back in 2011, Bloomberg appeared at a breakfast event where he was asked to weigh in on the Occupy Wall Street protests, which were then still at their anarchic peak. The mayor, who had made his fortune selling expensive information terminals to financial firms and was generally a booster of New York’s banking industry, proceeded to explain that he thought the demonstrators were blaming the wrong guys in suits.

“It was not the banks that created the mortgage crisis,” he said, as Politico reported at the time. “It was, plain and simple, Congress who forced everybody to go and give mortgages to people who were on the cusp.”

Bloomberg added, somewhat oddly, that he wasn’t sure whether the federal government’s affordable housing policies were a “terrible” idea, since they’d helped many low-income people become homeowners. But the housing boom and bust, he insisted, was most definitely Congress’s doing. “They were the ones who pushed Fannie and Freddie to make a bunch of loans that were imprudent, if you will,” he said. “They were the ones that pushed the banks to loan to everybody. And now we want to go vilify the banks because it’s one target, it’s easy to blame them and Congress certainly isn’t going to blame themselves.”

The idea that government policy, and not irresponsible, uncontrolled risk-taking by Wall Street, was the main cause of the housing crash is a popular line among many conservatives, but has never, ever been credible—Joe Nocera memorably called it the right’s “big lie” about the recession, in a 2011 New York Times column published not long after Bloomberg’s remarks. The myth rested on two lines of argument, which are worth reviewing.

The first claimed that banks started churning out subprime mortgages in response to the Community Reinvestment Act, a 1977 law that was designed to encourage lending in low-income neighborhoods. Blaming a Carter-era piece of legislation for an economic catastrophe that took place three decades later might seem a bit odd to some. But adherents of this notion argue that banks lowered their credit standards after Washington regulators began enforcing the act more stringently during the mid 1990s.

The theory had glaring holes, however. At the apex of the housing bubble, only a tiny fraction of the subprime mortgages originated or purchased by banks had anything to do with the Community Reinvestment Act. The loans that banks did make to satisfy the statute didn’t have particularly high default rates, either. Meanwhile, approximately half of the risky loans swirling through the financial system were made by non-bank lenders, like Countrywide Financial, that weren’t even covered by the CRA. It seems less likely that those mortgage mills were responding to regulations that didn’t apply to them than that they were just chasing a profit.

The second line of argument suggested that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the quasi-private mortgage finance giants that would eventually end up nationalized during the crisis, fueled the subprime boom as they tried to fulfill their own affordable housing requirements. This idea rested almost entirely on the work of Edward Pinto, a researcher at the conservative American Enterprise Institute who was a former vice president at Fannie Mae until the late ‘80s, and his think tank colleague Peter Wallison, who served on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. Pinto produced an analysis showing that there were 27 million “subprime” and Alt-A mortgages outstanding in 2008, and that Fannie and Freddie bore risk on 12 million of them in order to hit their affordable housing targets. The numbers made it sound as if government policy was at the very of core the entire housing meltdown.

They were also badly misleading. As law professor David Min showed, Pinto relied on an unusually broad definition of “subprime” that included many loans that weren’t particularly high-risk and had normal default rates. Moreover, 65 percent of the supposedly “risky” loans on Fannie and Freddie’s books wouldn’t have counted toward its affordable housing goals anyway. The companies did buy a large number of subprime mortgage backed securities at the height of the bubble. But they seem to have done it largely because of pressure from investors to up their profits—their own executives admitted as much—and were following the rest of the market rather than driving it. When the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission delivered its final report on the causes of the crash, and Wallison wrote a dissent relying on Pinto’s data, his views were considered so fringe that not a single other member, Republican or Democrat, joined him.

All of this history has been written about many times before. But what’s important to realize is that these issues had been litigated at length well before Bloomberg decided to blame the government for the crash. Researchers at the Federal Reserve were busy exonerating the Community Reinvestment Act back in 2009. Min was eviscerating Pinto’s and Wallison’s arguments in early 2011. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report dropped that January as well. And yet, there was the mayor of New York, echoing a thoroughly debunked right-wing theory of the case in late 2011.

And what does Bloomberg think caused the recession now? I’m not sure. I emailed his press team asking whether the mayor’s opinions about whether banks caused the housing crash have changed, but haven’t received a response. In the meantime, I haven’t been been able to find any evidence that Bloomberg ever walked back his position—though he has certainly trashed the Dodd-Frank Act’s reforms, which were supposed to reign in Wall Street’s most reckless habits. “The trouble is, if you reduce the risk at these institutions, they can’t make the money they did,” Bloomberg told a finance trade group in 2014. “If they can’t make the money they did, they can’t provide the financing that this country and this world needs to create jobs and build infrastructure.”

The 2008 financial crisis was the single most important economic event of this century—and possibly since the Great Depression. The fact that Bloomberg embraced a discredited right-wing explanation of it should badly undercut the idea that he’s a careful, numbers-driven technocrat. Even if he’s changed his mind now, as he says he has over stop-and-frisk, how do we know he won’t make the same mistake again?

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/37z3Lod

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言