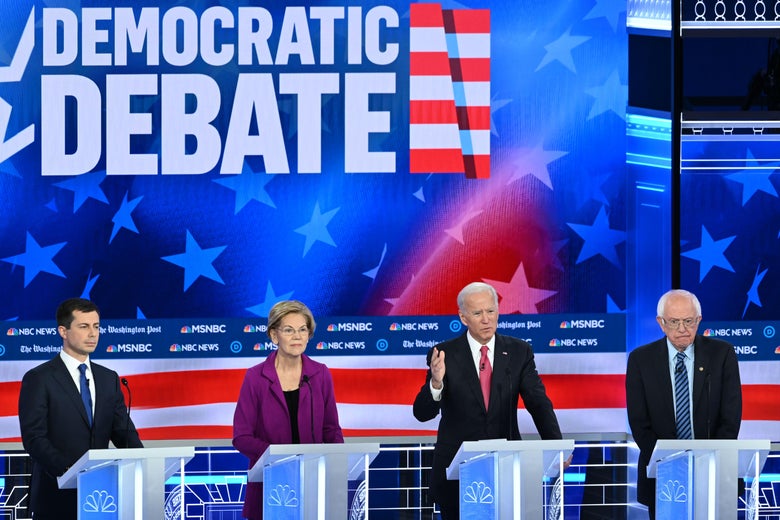

Democratic presidential hopefuls Pete Buttigieg, Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, and Bernie Sanders speak during the fifth Democratic primary debate in Atlanta, Georgia on November 20, 2019.

SAUL LOEB/Getty Images

About two-thirds of the way through Thursday night’s Democratic presidential debate in Atlanta, Sen. Kamala Harris was asked about her recent criticism of Pete Buttigieg’s superficial outreach to black voters. By the fifth debate, just a couple of months before the first voting contests, this sort of question would usually serve as an invitation from the moderators for a candidate to tear into a rival who’d experienced the most recent polling surge, and appears a threat to become the new leader.

Harris, though, said that she’d only said that because a reporter asked her for a response, and that she wouldn’t pile on the Buttigieg campaign, since it had already apologized for the offending incident. She pivoted, instead, to a much less vicious, but still effective, monologue about the way Democratic candidates have too often taken black voters for granted.

That was the tone of the proceedings, which lacked the sharp clashes with, or among, top-tier candidates that marked the last few debates.

It most strongly resembled the first debate in late June, when the candidates were still introducing themselves to the electorate. That may have been because it was the first debate, effectively, in which there was no designated frontrunner. The race has flattened.

In the last debate, in mid-October, the candidate to be taken down was Warren, who had risen to the top of national, Iowa, and New Hampshire polls. That debate seemed to be the rare one that actually shaped the trajectory of the race for longer than the next 24 hours. The criticism over Warren’s “evasive” answers on her Medicare for All plan, coming numerous rivals, hounded her for weeks afterwards, forcing her first to release a questionable financing plan and then, a couple of weeks later, to hedge on her commitment to passing a single-payer health care bill at all. The sustained questioning of her plan, and of her tactics around the plan, seemed to strike a chord with enough voters to make a change in the standings. In the well-respected Des Moines Register poll of Iowa caucus-goers that came out this weekend, a healthy 38 percent of likely Democratic caucus-goers described Warren as “too liberal,” while 48 percent found her “about right.”

Buttigieg, meanwhile, led that Iowa poll by nine percentage points and was deemed “about right” on his politics by 63 percent of voters. At her peak, Warren was wedged perfectly in that middle ground between Biden and Sanders. Now Buttigieg has squeezed into his own piece of middle-middle ground between Biden on one end and Warren and Sanders on the other.

It seemed likely, therefore, that Buttigieg would face the level of scrutiny that Warren had faced last time. That he did not face nearly that kind of assault, though, suggests how unconcerned the field is about Buttigieg as a long-term threat given his weakness among voters of color.

The South Bend mayor—the title alone being another reason to doubt his long-term prospects—does not have any support among black voters in certain polls. Really: In a recent poll of South Carolina, Buttigieg received zero percent support among black voters—and not for the first time.

So Buttigieg is surging in Iowa and New Hampshire but has no traction among voters of color who will dominate the races in Nevada, South Carolina, and Super Tuesday. Biden is still the strongest candidate among voters of color, but is falling back to third or fourth place in the first two states. Warren has been sliding, and Bernie is still stuck in his normal Bernie position of about 15 percent across the board, with no sign of either surging or collapsing. There is no frontrunner.

And when there’s no frontrunner, you get leading candidates largely playing nice with each other while second-tier candidates make their play for the enviable middle-ground position that Buttigieg is place-holding.

Sen. Cory Booker, for one, has got to feel insulted that donors are in a panic trying to recruit new, center-left, hopeful, and donor-receptive candidates, when that particular tune has been Cory Booker’s theme song for months. One couldn’t help but notice a couple of new, and telling, keywords in Booker’s repertoire. While he maintained his same strong passion for criminal justice issues, his economic pitches were more hedged. He went after Elizabeth Warren’s proposed wealth tax, and then said Democrats need to focus not just on taxation but on how to “grow wealth” as well. It’s a winning message in the CNBC primary.

And while Sen. Kamala Harris chose not to formally lay the hammer into Buttigieg during that moment, her speech contained a pitch that declared, via contrast, why she could be the consensus candidate in a way that Buttigieg could not.

“I’m running for president because I believe we have to have leadership in this country who has worked with and has the experience of working with all folks,” Harris said, coolly implying that perhaps the guy who’s at zero percent among black voters in a critical early state might not be this person. “And we’ve got to re-create the Obama coalition to win.”

“I keep referring to that,” she said shortly after her third or fourth reference to rebuilding the Obama coalition, “because that’s the last time we won. And the way that that election looked and what that coalition looked like was about having a leader who has worked in many of those communities, knows those communities, and has the ability to bring those people together.”

The way Obama won the nomination in 2008 was to pull off a surprise victory in Iowa and blowout in South Carolina, leading into a long winning streak of states, many of which had high African American populations. Kamala Harris, who’s focusing her limited resources on competing in Iowa now, is aware of this history when she repeatedly mentions the Obama coalition, and is signaling that she’s the candidate best positioned to put it back together.

As Booker, Harris, and Sen. Amy Klobuchar—another candidate who’s keeping a pulse in Iowa, and who used the debate to hammer her experience and record of bipartisan support in elections—vied for a last-minute surge into the flattened top-tier, the four leading candidates were mostly just themselves. Elizabeth Warren would promise to fight and then disappear from the conversation entirely for extended lengths. Joe Biden had some strong answers in the first half before his usual second-half surprise, which in this case involved the following sentence: “I come out of the black community, in terms of my support.” Bernie Sanders was Bernie Sanders, delivering the best answers on his best issues, and Pete Buttigieg delivered sound bites that he seemed to have memorized, for this exact moment in his life, when he was 11 years old. Tulsi Gabbard picked fights with people and lost them all.

The next debate comes in December, and so far only six candidates have qualified for it. Why risk trying to kill off your opponents, when the steadily rising debate entry standards can kill them off for you?

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2O9IKsF

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言