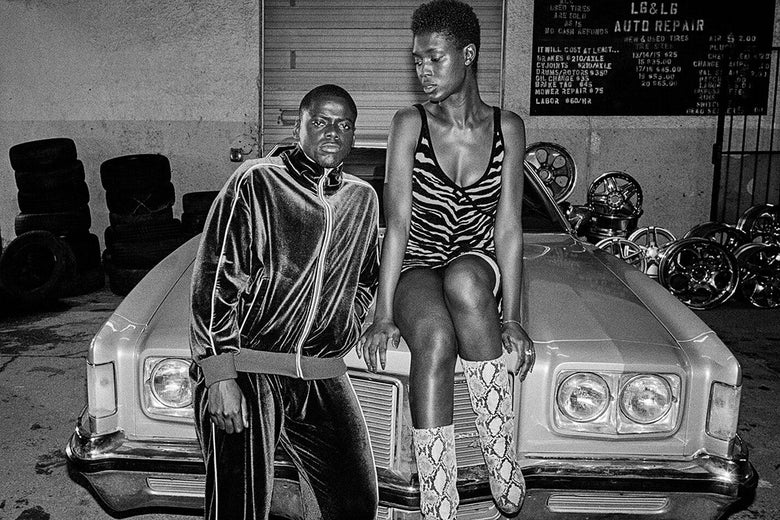

Daniel Kaluuya and Jodie Turner-Smith in Queen & Slim.

Universal Pictures

“Why do black people always feel the need to be excellent?” sighs the male half of the “black Bonnie and Clyde” of Queen & Slim. “Why can’t we just be ourselves?” A century and a half ago, black Americans were finally guaranteed the right, at least on paper, to consider their bodies their own, but many today would be justified in feeling only a tenuous control over their lives, especially when a police officer can end them with impunity. After a traffic stop leads to the killing of a white cop in self-defense, the central couple in Queen & Slim are forced to abruptly surrender the lives that they’d carefully built for themselves: he (Daniel Kaluuya) as a dutiful son who’s square and self-assured enough to pray before his meal on a first date and she (Jodie Turner-Smith) as a criminal defense lawyer prone to building walls around herself but desperate to let someone in. As soon as they’re pulled over by a racist cop who should’ve been taken off the streets years ago, their fates are sealed. Within hours, their tragedy becomes everyone else’s story.

Queen & Slim doesn’t reveal the names of its protagonists until the film’s coda—when it does so with great impact—so I’ll refer to them in this review by the nicknames given to them by the movie’s title. It’s worth noting that while both the fictional and historical Bonnies and Clydes were murderers, Queen and Slim mean no harm. Nonetheless, the fact that law enforcement has often been deadly slow to give black suspects the benefit of the doubt keeps them on the lam. Writer Lena Waithe and first-time feature director Melina Matsoukas (who helmed Waithe’s Emmy-winning “Thanksgiving” episode on Master of None, as well as numerous music videos including Beyoncé’s “Formation”) weave the grim fatalism with which Queen and Slim approach the criminal justice system with a romance that alternates between the intimate and the epic. A close cousin of Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk in their shared love of melancholy yearning, it is, to my mind, easily one of the best movies of the year. Give it a wheelbarrow full of trophies, and it’d almost make up for Green Book’s Best Picture Oscar.

Kaluuya is so extraordinarily expressive that you can see his every thought flit by.

Coincidentally, Queen & Slim is a road trip movie, too, one that follows a modern-day Underground Railroad in the opposite direction, south from Ohio to, well, where’s the Promised Land today? After briefly taking refuge with Queen’s uncle (a scene-stealing Bokeem Woodbine) in New Orleans, where they undergo drastic makeovers, the broke couple has no choice but to seek and trust a series of strangers. (For a pair of ostensible millennials who have ditched their phones, they evidently have no trouble finding street addresses in multiple states with nary a map.) Waithe and Matsoukas wring a great deal of suspense (and poignancy) from each one of Queen and Slim’s stops, where the couple discover that they’ve become not only wanted fugitives but also folk heroes and a cause célèbre. (The dead officer’s camera footage demonstrates their innocence, while capturing the cop grazing Queen’s thigh with a bullet.) Queen and Slim are grateful for the support insofar as it occasionally helps with the logistics of escape, but they’re baffled, too, to be considered more symbol than human. When a young black teen enamored of the outlaws muses that his own curtailed life might grant him immortality, Queen quickly rejects the idea of being turned into a memorial: “I’d rather live.”

When even their well-wishers are turning them into stand-ins, Queen and Slim’s only mode of resistance is insisting on their humanity. But the love story—an unexpected arranged marriage, of sorts—is also where the movie’s ambitions outpace its artistry, resulting in the occasional scene that feels forced. (To be fair, it’s a lot to ask a random Tinder hookup to transform in a few days’ time into your ride or die.) The romantic dialogue can veer toward the precious and self-consciously writerly, and the deepening of Queen’s family history—the only time when the movie stalls—seems to be at the expense of Slim’s own backstory, which could’ve been developed further. But even with such bare characterization, Kaluuya, showing a more vulnerable side of himself after his guarded turns in Get Out and Widows, is so extraordinarily expressive that you can see his every thought flit by. Turner-Smith is slightly less notable (which is to say still quite wonderful) in a showier role that finds a sharp-tongued but seemingly put-together professional slowly revealing layers of disillusionment and raw need. And despite her education—or maybe because of it—Queen sometimes chooses her dignity over safety, as does Slim. It’s a strange relief to see the duo occasionally less than tactical, even irrational, just like anyone would be when they’ve been driving for hours while paranoid, sleep-deprived, and ravenous.

Ten minutes before the closing credits, I was confident I knew how their story would conclude. I was wrong—I’d collected the clues that the script had laid out and pieced them together in the most conventional manner possible. While Bonnie and Clyde shocked audiences in 1967 with its nihilistic shootout of a denouement, Queen & Slim uses its couple’s end of the road for a constellation of circumstances much more devastating—and hopeful. There’s a particular thrill when all of a film’s many story elements—here, so dense with symbolism—come together with such thematic and emotional vigor. That intensity pairs exquisitely with the tenderness the film never wants to lose sight of. It’s embodied best by the unhardened Slim, who, in his few relaxed moments, leans back to gaze admiringly at Queen, wholly unbothered by her two or three inches of height above him. He doesn’t need their love story to look like everybody else’s.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/34iDmIZ

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言