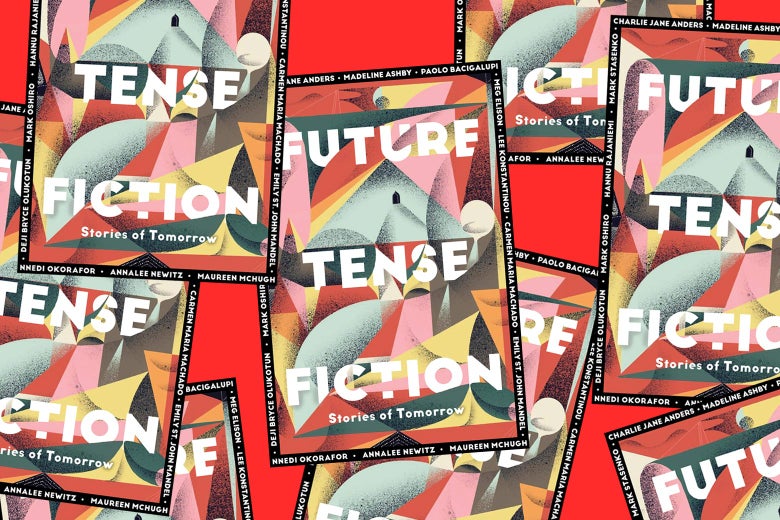

Photo illustration by Slate.

On Oct. 30, authors Meg Elison, Annalee Newitz, and Hannu Rajaniemi will be in San Francisco’s Green Apple Books on the Park to discuss science fiction, the imagination, and the new anthology Future Tense Fiction, in which they each have a short story. For more information and to RSVP, visit the New America website.

Nobody can see the future, but science fiction authors often picture a future—one possible vision of what the years to come might look like. In the recently published anthology Future Tense Fiction: Stories of Tomorrow from Unnamed Press, 14 speculative fiction writers looked at visions of smart homes, sports, time travel, robots both murderous and protective of humans, and more. Future Tense Fiction is a series of short stories from Future Tense and ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination about how technology and science will change our lives.

To celebrate the publication of Future Tense Fiction, co-editor Joey Eschrich moderated a Slack discussion with authors Madeline Ashby and Charlie Jane Anders, who both have stories in the collection. In Ashby’s “Domestic Violence,” a woman’s smart home is turned against her by an abusive partner. In Anders’ “The Minnesota Diet,” a group of hip tech workers living in a futuristic city called New Lincoln find themselves facing a food crisis caused by political gridlock and supply chain meltdowns.

In the discussion below, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, they talked about the interaction between sci-fi authors and scientists, the role of fiction in policymaking, and asking the question “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Joey Eschrich

You were both among our first authors in the Future Tense Fiction series, and you both wrote memorable and mind-bending (but very tonally different) stories. Where did those ideas start? What was the spark?

“People in the U.S. are bad at thinking about any problem until we see it affecting people like ourselves.” — Charlie Jane Anders

Madeline Ashby

I’d had the idea for “Domestic Violence” for a couple of years, at least. I had written another smart home story, called “Social Services,” for the Institute for the Future, and the other stories in that anthology were all haunted house–type stories in one way or another. So it made me think of the other, darker ramifications of smart home technology, and the obvious one for me was abuse.

Charlie Jane Anders

Writing these sorts of stories is a really fun way to think about what’s going on right now, and to try and peer into the corners of stuff that people might not be looking into. My story came out of thinking about famine, specifically. Famine is a huge issue right now, and it’s going to be much more widespread and terrifying in the decades to come.

Joey

And your story puts it among people who seem fairly privileged, in the U.S., with loads of cultural capital.

Charlie Jane

I think that people in the U.S. are bad at thinking about any problem, no matter what, until we see it affecting people like ourselves. So yeah, I decided to write about famine affecting middle-class knowledge workers in an advanced city in the United States. And the more I started looking into it, the more this felt like a real thing, that our increasingly dense cities could be at risk of food insecurity if we’re not careful.

Madeline

Oh my, yes.

Charlie Jane

Much like the smart home thing, I feel like there’s a lot of triumphalism about future cities, including “green” cities. And I wanted to offer a bit of a corrective to that.

Joey

Both of your stories are also about biases built into tech systems—these triumphalism symbols of the future—that are really tricky to trace, but can have profound or even disastrous effects on people’s lives. Did you each have that in mind when you were coming up with the stories?

Madeline

Yes, definitely. It’s been really encouraging to see more mainstream news sources start covering issues like algorithmic bias. It’s a story that I think a lot of people in the tech-criticism and critical-futurist communities have been following for years now, but to watch this kind of bias become part of common parlance has been really interesting.

Charlie Jane

Yeah, I think a lot of the story of the past 20 years is the law of unintended consequences rearing its ugly head. There’s this misconception that tech is neutral, or that it results from some kind of ideal process of finding the “best” version. Whereas usually it’s more a matter of the people involved reiterating their biases and preconceptions at scale. Tech is not going to change human nature that drastically, and it’s always going to be used for things the designers didn’t envision.

Madeline

Yeah, “the street finds its own uses for things”—that doesn’t change.

Joey

In narrative terms, I guess that often leaves characters wondering where the levers are to pull or buttons to push. In both “Domestic Violence” and “The Minnesota Diet,” we see characters stymied for a while about how to intervene. The edges have been so carefully sanded down on the technologies.

Charlie Jane

Yes, absolutely. That’s something that always bugs me, the ways that tech is designed to be opaque.

Madeline

Right, I think that’s the nature of writing about a consumer product. It’s not the same as writing about a big dumb object, like a space elevator or something. You’re writing about something that has been made, in theory, user-friendly. So it has to look that way on paper, too. And it has to have all the bugs that “user-friendly” things have, too.

Charlie Jane

In my story, the big mechanism driving everything (no pun intended) is these driverless trucks that are supposed to bring supplies to New Lincoln, but they keep getting rerouted.

Madeline

Ooh, nice.

Charlie Jane

Thanks!

Joey

And thus, who do the makers of the technology have in mind as their customer? Who gets left out of that? Or in the case of the trucks, what’s the system logic driving decisions about food delivery?

Charlie Jane

My story didn’t really “click” until I decided to start it with just a view of the trucks zooming across the landscape, and it’s pretty clear that there’s no human being involved in their routing. I think that these systems start out with good intentions and then just gradually get more and more unwieldy as more complexity is added.

Madeline

Right, and complexity is treated as a threat to the system. The system is actively hostile to nuance.

Charlie Jane

Yes! That is a great way of putting it.

Madeline

Mostly because nuance requires humans, and humans cost more.

Charlie Jane

I think a lot of thought went into making New Lincoln a nice place to live, and not a lot of thought went into the question of how to feed all those people.

Joey

In both stories, the makers/designers are off-screen—we don’t see them or get to hear from them. It’s just the characters working with each other through the tech or grappling with the limited interfaces.

Madeline

Three months after “Domestic Violence” debuted, there was a story in the New York Times about exactly the same thing. Just, real-life instances of smart home technology being leveraged against victims of intimate partner violence. So clearly other people were concerned about it.

Joey

Do you often get approached by specialists in science/tech or other fields you write about? Like, after you publish something, even much later?

Madeline

Sometimes. I did an event at the Institute for Machine & Human Cognition in Pensacola, Florida, this year, probably in part because I’d written a book about families of robots who eat each other.

Charlie Jane

I’m more likely to seek out experts and bug them with questions!

Joey

I’d wondered if you had people kind of wanting to fact-check after reading! When I edit I always worry, because I’m usually so out of my depth on the tech/science end of the storytelling.

Madeline

Probably the best experience I had with that was working on a story called “Death on Mars,” for another Arizona State University Center for Science and the Imagination project, and I got to talk to people at NASA. And that was great. One of them even agreed to appear over Skype for my science fiction film class at OCADU, later.

Charlie Jane

I worry constantly about getting my science right, but then it always turns out that the one thing people are annoyed by is something I never thought of in a million years. I have found scientists and other experts unfailingly helpful and generous and extremely kind to my flawed attempts to present their work in a (hopefully) entertaining story. I was at Annalee Newitz’s book event in L.A., and they were talking to Sean Carroll, who advises Hollywood films on science. Sean was saying he tells people, “Treat whatever weird science thing happens in the story as data.” In other words, don’t say, “That couldn’t possibly happen.” Instead, just say, “OK, so the premise of this movie is something that has happened (in the context of the story). If I was presented with this data in real life, how would I try and explain it?” Which is a really fun way of looking at it.

Madeline

It’s like an alibi, but for science.

Joey

When it’s something commissioned, especially with some of the science fictional consulting work you do, Madeline, are those expectations of fidelity ramped up at all? Or changed?

Madeline

Hmmm. That’s tough to say. It depends on the fidelity/granularity/specificity of the ask. If I get a huge document about something that’s already in development, that’s one thing. If the ask is more broad—like “Can I have a story about a future world without antibiotics?”—that’s something else.

“It’s like an alibi, but for science.” — Madeline Ashby

But deep down, all of those stories are answering questions like: “How will humans actually interact with this? What might someone use this for?” At its best, it surfaces questions and concerns that weren’t already in the mix. My favorite question is: “What’s the worst that can happen? Can you write a story about that?” People don’t ask it very often, but that’s when they get the best results.

Although, naturally, the question arises: “Worst for whom?”

Joey

Over the past several years, science fiction has played a bigger role in decision-making and planning, in the private sector and in nonprofit, government, etc. Have you noticed that too, and how has it affected the genre and your own work lives?

Charlie Jane

I feel like I see a lot of lip service paid to science fiction, particularly things like Black Mirror or Star Trek, but not a lot of deep consideration of it in the public policy space. It’s a cultural touchstone but doesn’t actually have as deep an impact as I would like.

Madeline

I have noticed it more, and it’s a huge part of my work life. I write more science fiction prototypes, foresight scenarios, etc., than I do short stories on spec. In fact, my agent probably wishes I did less of it. But the penetration on those stories goes only so far. I once wrote one that only six people ever saw. So it’s hard for it to become a touchstone. But lots of companies and organizations use it as a way of enhancing a conversation about a particular thing.

Joey

It does seem like a lot of criticism and public discussion of the genre focuses on movies, like the recent backlash against dystopian/end-of-world stories, but then it’s kind of broadly applied to written fiction as well, which is so much more diverse and voluminous.

Madeline

Right. Well, that critique of cinema is a lot easier, because it’s part of a visual language of the future that a lot more people have in common. If I say “gestural computing,” you might not know what I mean, but if I say Minority Report or Iron Man, and I wiggle my hands in the air, it’s instantaneous.

Charlie Jane

I feel like a lot of stuff that used to be only tackled in books and stories is now finding its way into movies and television in a way it hasn’t since the 1970s.

Joey

OK, last question! If you could recommend one piece of science fiction to the 2020 U.S. presidential candidates, what would it be?

Madeline

This is easy: Theory of Bastards by Audrey Schulman. It’s about an evolutionary biologist who studies monogamy, or the lack thereof, in our primate ancestors. She also happens to suffer extreme endometriosis, and she’s just had a surgery that will allow her to work without pain for the first time in her life. Naturally, this is the moment when everything goes to hell: There’s a huge communications collapse, and she’s stuck at a zoo, with her tribe of bonobos, and a man who’s trying to teach them flint-knapping.

Charlie Jane

Oh wow. Hmmm. I would say K.M. Szpara’s Docile.

Madeline

Ooh, good call.

Charlie Jane

Although I don’t know how the candidates would respond to all the gay sex. It’s such an important book about debt and inequality.

OK I need to run! 🙂

Bye!!!!!

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/32MONYS

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言