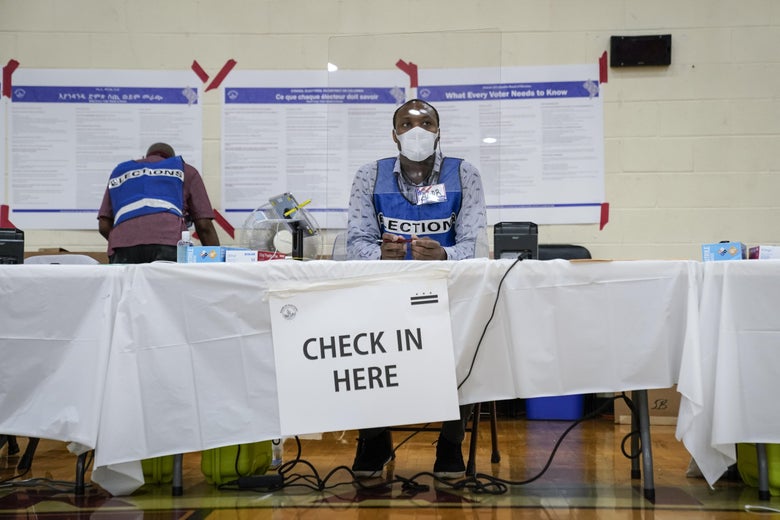

A poll worker wears a mask and sits behind a plastic barrier as he waits to check in voters at a polling place on June 2, 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

On Tuesday, as law enforcement officers swarmed the District of Columbia in response to largely peaceful protests against police brutality, the city attempted to hold a primary election. It was an unmitigated disaster. Thousands of residents who requested an absentee ballot never received one. They were forced to vote in person in the midst of a pandemic, waiting in monstrously long lines that snaked around multiple city blocks. And although Bowser exempted voters from the 7 p.m. curfew, not everyone got the memo: several officers reportedly issued dispersal orders to voters waiting in line to cast a ballot. The district’s election provided one of the starkest examples of voter suppression so far this year.

That is not to say that city officials intended to disenfranchise voters. Rather, Tuesday’s breakdown was a combination of negligence and bureaucratic mismanagement against a backdrop of a historic public health crisis and a federal effort to crush an uprising. Bowser hoped to conduct the election primarily by mail so voters would not face potential exposure to the coronavirus by voting in person. Her administration launched a campaign urging everyone to request an absentee ballot. But while 92,000 voters requested a ballot, many never received one. One advocacy group interviewed 75 voters in line on Tuesday and found that a third of them did not get their mail-in ballot. To address the problem, election officials began hand-delivering ballots—then, finally, simply emailed some to voters, an untested and insecure procedure strongly opposed by voting rights advocates.

If Washingtonians could easily and safely vote at their neighborhood precinct, this vote-by-mail backlog might not have been catastrophic. But Bowser’s administration consolidated D.C.’s many precincts into just 20 voting centers for a city of 700,000, anticipating reduced turnout due to widespread absentee voting. These centers opened for early voting on May 22. By late May, it was clear that the D.C. Board of Elections botched vote-by-mail. Yet the city made little effort to encourage in-person early voting as an alternative for those who didn’t get their ballots on time. So, understandably, many Washingtonians who applied to vote by mail waited until Tuesday to receive their ballot—only to realize, after the mail arrived, that it wasn’t coming. They could not wait any longer, because mail-in ballots had to be postmarked by Election Day. So these residents had to vote in person or forgo voting altogether.

As a result, hundreds of residents waited in lines at voting centers only equipped to handle a small number of people. The D.C. Board of Elections’ official line tracker never reported a wait time longer than 90 minutes. But at the Columbia Heights neighborhood center, which I visited on Tuesday evening, voters at the front of the line said they had been waiting for three hours. And by that point, the line had nearly doubled. Voters at other polls waited for five hours. The last voters cast their ballots around 1:30 a.m. Most tried to maintain social distancing, but it was difficult on cramped sidewalks, and some grew irritable as the evening dragged on. There were also moments of solidarity—as when, once curfew began at 7 p.m., voters in line at a Van Ness poll took a knee in honor of George Floyd.

At one voting center, a police car drove by and announced that voters waiting in line had to go home because of the curfew.

In an interview with the Washington Post, D.C. Board of Elections chair Michael Bennett seemed to place the blame on voters. “The bad news,” Bennett said, “is everyone decided to vote on the last day that vote centers are open and they decided to do it in person, and that just created an incredible logjam when you consider the fact we are in the middle of a pandemic.” (The “last day that voter centers are open” is also known as Election Day, and countless voters had no choice but to vote in person because they never got a mail-in ballot.)

Bowser’s initial curfew order did not exempt voters—even though curfew began at 7 p.m. while polls did not close until 8 p.m. (This gap was arbitrary and unnecessary, and opposed by at least one councilmember.) In response to a media inquiry from who/what outlet, her office clarified that voting was exempt from the curfew. But it refused to explain how voters could verify to law enforcement that they were traveling to or from the polls. This was no small matter, as violators of the curfew faced 10 days in jail or a $300 fine. Then, on Monday, Metropolitan Police Chief Peter Newsham announced officers would check “credentials” to determine if someone breaking curfew is really a voter. (Since the district has no voter ID law, it is unclear what credentials the police might check.)

This haphazard plan worked about as well as you might expect. At one voting center, a police car drove by and announced that voters waiting in line had to go home because of the curfew. Kevin Donahue, the district’s Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice, tweeted, “We seem to have 1 officer here who messed up.” But that claim was false: Two police cars pulled up to a different voting center and announced: “The Mayor has declared a 7 p.m. curfew! Go home!”

Law enforcement officers issuing dispersal orders to voters is the kind of heavy-handed disenfranchisement one might’ve seen in the Jim Crow South. Today’s progressive jurisdictions generally do not tolerate official threats to strip hundreds of citizens of their constitutional right to vote. Yet Donahue immediately downplayed reports of police unlawfully harassing voters, an ominous sign that the city will not take these incidents seriously or discourage officers from bullying voters in the future. (Neither Donahue nor the Bowser’s office has responded to repeated requests for comment.)

The stakes for a local primary may seem low, but in heavily Democratic D.C., most races are effectively decided in the primary. Yet the mail-in ballot meltdown, five-hour lines, and threat of police intimidation surely dissuaded residents from casting a ballot. The winners of this election will not represent the district, but rather the district residents who had the time, resources, and sheer luck to overcome these obstacles to the franchise. While the federal government cracked down on peaceful protests in D.C., the city’s leaders had an opportunity to demonstrate respect for constitutional liberties and protect its residents from federal overreach. Instead, they empowered law enforcement to intimidate voters, reinforcing the attack on DC residents’ fundamental rights.

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary, and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plusfrom Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3eL2CfP

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言