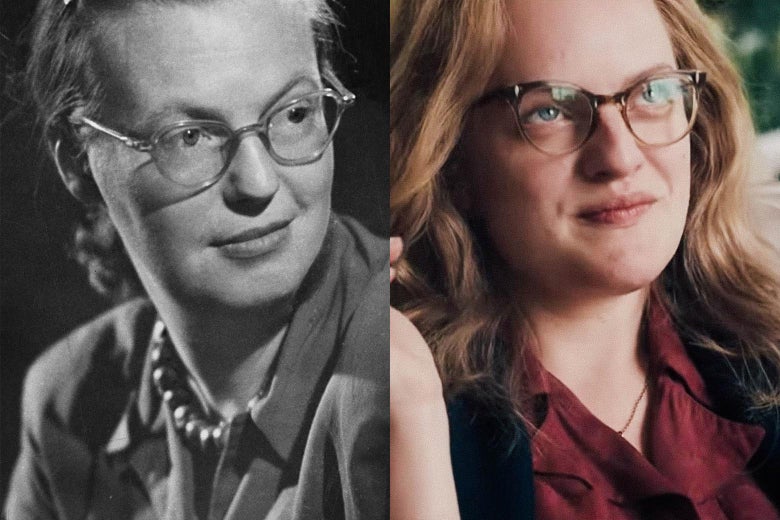

Shirley Jackson, and Elisabeth Moss as Shirley Jackson in Shirley.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by AP and Neon/Sundance.

Shirley, director Josephine Decker’s new film about a few months in the life of the writer Shirley Jackson, aims to resemble a Shirley Jackson story of the very spikiest variety. It has a soundtrack full of violin strings being scraped now and then in a seemingly random fashion, and lots of tilted shots of tree branches and disorienting cuts to scenes of hallucinatory menace. Jackson, most famous for her short story “The Lottery,” specialized in fiction about women losing it, their identities fracturing into shards of rage and alienation. Although she is sometimes categorized as a horror writer, few of her novels and stories feature supernatural forces, and even then, the spooks are so thoroughly muddled up with the characters’ psychological disintegration that it’s often hard to tell the difference.

What Shirley isn’t is a remotely accurate biopic of the author. The movie is not based on either of the two existing biographies—1989’s somewhat louche Private Demons by Judy Oppenheimer and Ruth Franklin’s definitive Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, published in 2016. For source material, screenwriter Sarah Gubbins used a 2014 novel, Shirley, by Susan Scarf Merrell, that registers somewhere between fan fiction and an homage to the Edward Albee play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

What Shirley isn’t is a remotely accurate biopic of the author.

The novel, and seemingly the film as well, is set in the last year of Jackson’s life. (She died in her sleep in 1965, at age 48.) An entirely fictional young couple, Rose and Fred Nemser (Odessa Young and Logan Lerman), come to stay with Jackson (Elisabeth Moss) and her husband, the English professor and literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman (Michael Stuhlbarg), in their rambling old house in Vermont. Fred hopes that Stanley, a tenured professor at Bennington College whom he’s been hired to assist, will help boost his own scholarly career. Stanley, it soon becomes clear, views the couple as exploitable labor: Rose as a de facto housekeeper who will take on the domestic duties of his depressed and creatively blocked wife, and Fred as a worshipful, if intellectually mediocre, academic grunt. A fan, Rose gradually wins over the mistrustful, glowering writer, and the two of them talk through Shirley’s idea for a new novel, to be called Hangsaman, based on a Bennington student who disappeared after telling her roommate she was going out for a long walk. Shirley begins to write again, but as Rose, who is pregnant, becomes acquainted with the less savory side of faculty wifedom, she entertains ideas about how her hosts might have been involved with the missing girl.

This makes Shirley sound a bit like a thriller, but it’s largely a showcase for two commanding performances from Moss and Stuhlbarg. Stuhlbarg might just have the edge. His Stanley is full of deceptively menschy bonhomie, handsy with Rose and paternalistic with Fred until the younger man’s back is turned, at which time he gripes to Shirley about Fred’s dissertation: “If it was awful, that would have been exciting. But terrifically competent: There’s no excuse for that.” He rants, with the justifiable shoulder chip of the mid-20th-century self-made Jewish intellectual, about Fred’s Ivy League entitlement but (like the real Hyman) never questions his own blithe expectation that the women in his life will wait on him hand and foot.

Moss’ Shirley is a showier performance, but the part is surprisingly underwritten. This Shirley is sarcastic, surly, and transparently manipulative, her fury over her husband’s affairs on a perpetual simmer that can boil over at any minute. Anger has always been Moss’ forte, and she is genuinely scary whenever Rose unwittingly incites Shirley’s free-floating ire. It’s hard to see why the younger woman is so smitten with the troubled writer—and that’s despite a brief episode of lesbian dalliance between the two, an attraction that surfaces and then vanishes without any apparent effect on the relationships in the film. (Jackson’s biographers have speculated about her sexual orientation, based mostly on a peculiar allusion to lesbians in one of her journals, but there is no evidence she acted on such desires, if she ever had them, let alone as confidently as the Shirley in Shirley does.)

Possibly the filmmakers mean this and some of the other interactions between Rose and Shirley—or maybe even the entire movie—to be fantasies. Young bears a strong resemblance to Moss, and also appears in dreamlike sequences as Paula, the missing Bennington student. Shirley, too, identifies with this “lost girl,” a figure she sees as the embodiment of countless lonely young college women who “cannot make the world see them.” Stanley keeps telling her the subject is trivial and irrelevant until eventually she shouts back at him, “Don’t tell me I don’t know this girl!” Yet neither sultry Rose nor intimidating Shirley seems much like Paula or the wallflower protagonist of Hangsaman, a novel that, incidentally, Jackson published in 1951, more than a decade before the action in Shirley takes place.

Also, Jackson and her husband were living in Connecticut when she wrote that book, along with their four small children, who have been completely erased from the film version of the marriage even though they were still living with their parents. In the movie, it’s just Stanley and Shirley knocking around their creaking, book-lined house, making cutting remarks and knocking back cocktails. The film’s Shirley may be enigmatic, but the real one was even more so. Her home was in fact loud, boisterous, and full of company, cats, and children, whose hilarious exploits were the subject of humorous essays Shirley sold to women’s magazines. Those pieces, which are tremendously fun, supplied the couple with the majority of their income. Meanwhile, Jackson wrote disturbing fiction about some of the loneliest people ever committed to the page.

Jackson had her demons, including the bout of agoraphobia depicted in Shirley. And her husband’s infidelities did provoke her, although probably not to the venomously profane outbursts exhibited by Moss’ Shirley. (Jackson’s fiction is strikingly devoid of sex, and she was so inhibited in this respect that her daughter recalled that, around the time this film is set, she had to teach her mother how to pronounce the word fuck.) Shirley takes the Albee-esque position that Shirley and Stanley had achieved a sometimes painful but nevertheless invincible symbiosis that no outsider could ever penetrate. He championed her genius from their undergraduate years, when he read one of her stories in their college newspaper and vowed to marry the author sight unseen (a true story). Stanley’s unflagging faith in her work keeps the fragile Shirley from losing it entirely. The price she pays is putting up with his ephemeral affair.

At the heart of Shirley lies the question of whether the marital bargain is worth it. In Rose, Shirley sees (perhaps literally!) a version of her younger self, one who still has a chance to escape before the terms of the deal are irrevocably set. Apart from the missing Paula, Bennington’s students only appear in the film as smiling, nubile sirens, performing impromptu interpretative dances under a tree and cooing in tartan skirts in the classroom. (This is, by most accounts, an accurate representation of the women’s college before it went coed.) The real Jackson loved being a homemaker, especially cooking and raising children, but she also sometimes felt trapped. For all its inaccuracies and elisions, Shirley really does get at its namesake’s ambivalence about domesticity and marriage. When she died, Jackson was not writing Hangsaman but a very different sort of book, of which only a fragment was ever completed. She considered it a breakthrough. Titled Come Along With Me, it’s the cheerfully sardonic story of a woman whose husband dies—the reader does wonder how, exactly—and who sells her house and every last object in it to her nosy, judgmental neighbors. Then she packs a bag, gets in her car, and drives off into the great unknown. However much she differs from the historical Shirley Jackson, the title character of Shirley, too, dreams of freedom and never gets it, except in her dreams.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2zSJcXJ

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言