2017年10月31日 星期二

Thors Helmet Emission Nebula

Renaming A Rocket To Get A 100% Success Rate

|

|

Orbital ATK Successfully Launches Minotaur C Rocket Carrying 10 Spacecraft to Orbit for Planet

"Orbital ATK ... announced its commercial Minotaur C rocket successfully launched 10 commercial spacecraft into orbit for Planet. The Minotaur C launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California."

Minotaur-C, Wikipedia

"Minotaur-C (Minotaur Commercial), formerly known as Taurus ... Three of four launches between 2001 and 2011 ended in failure."

from NASA Watch http://ift.tt/2yjSnhU

via IFTTT

Learning to Walk Before Heading to Space

ISS Daily Summary Report – 10/30/2017

October 31, 2017 at 12:00AM

from NASA http://ift.tt/2gRH2L3

via IFTTT

After Cassini, What’s Next for the Outer Planets?

Casey Dreier • October 31, 2017

After Cassini, What’s Next for the Outer Planets?

It was big news when the Cassini mission met its dramatic end at Saturn last month. But The Planetary Society likes to look ahead, and that spirit we organized a reception at the Library of Congress to bring scientists, legislators, and their staff together to honor Cassini and get excited about our future in the outer planets.

Ellen Stofan, the former NASA Chief Scientist, addressed over 150 attendees in the James Madison Memorial Building of the Library of Congress. Our exhibitors had the opportunity to share their roles in upcoming missions, from James Webb to New Horizons to Juno to Europa Clipper. And four members of Congress were able to join us that day to learn about the scientific opportunities in the outer planets.

These events are an important part of our work in Washington, D.C. Not only does it allow members of Congress and their staff to engage directly with scientists, but it helps generate excitement, inspiration, and engagement for the possibilities that lie before us in the outer planets. Getting people excited about the upcoming Europa Clipper mission will help build interest in potential missions to the ice giants of Uranus and Neptune. We wanted to send a message: Cassini may be done, but the future is full of opportunity, and that future depends on decisions we make today.

It is only because of the support from our dedicated membership that The Planetary Society is able to organize educational events like this in Washington, D.C. We have been able to grow our staff and commit additional resources due to our donors and supporters, which allows us to be even more nimble and active in the U.S. capitol while we promote space science and exploration.

The Planetary Society in D.C. is fortunate to have highly dedicated volunteers, and we could not have put this event together without them. In particular, Antonio Peronace and our D.C. volunteer coordinator Jack Kiraly committed extraordinary amounts of time and energy making this event a success.

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Support enables our dedicated journalists to research deeply and bring you original space exploration articles.

Member Login

© 2017 The Planetary Society. All rights reserved.

Terms of Use The Planetary Society is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

from Planetary Society Blog http://ift.tt/2A3ZCrm

via IFTTT

2017年10月30日 星期一

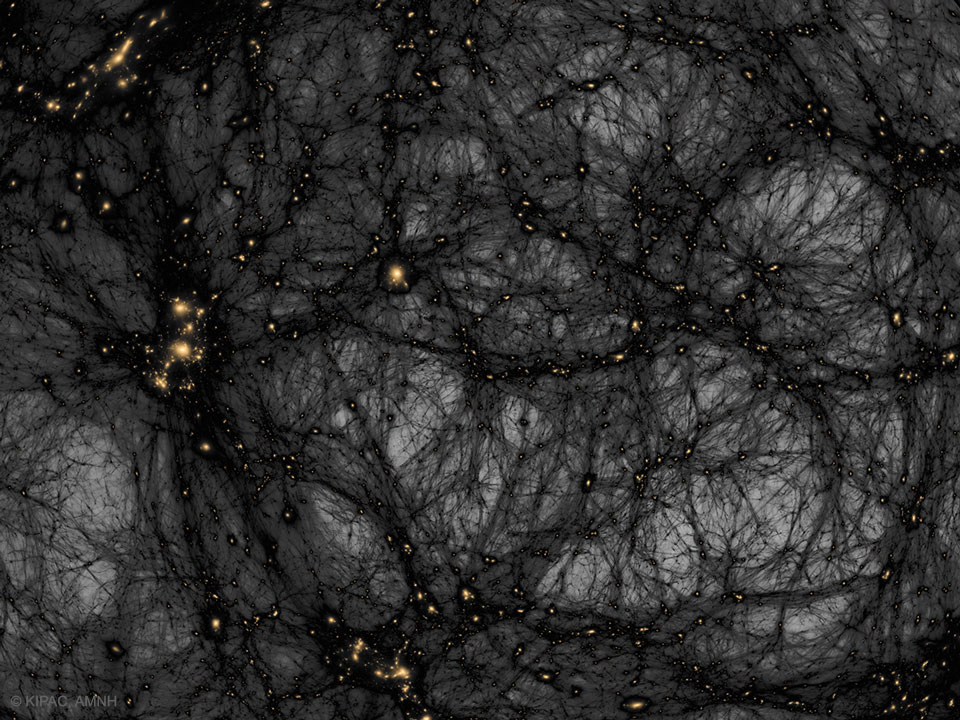

Dark Matter in a Simulated Universe

#DPS17: The Moon's Giordano Bruno crater through many eyes

Emily Lakdawalla • October 30, 2017

#DPS17: The Moon's Giordano Bruno crater through many eyes

The Division for Planetary Sciences meeting has been over for a week and I'm still processing my notes. Today's story is about a presentation by Sriram Bhiravarasu on some interesting minerals mapped around a fresh crater on the Moon. Like the other talks from DPS that I've been writing up, it's not an Earth-shattering result, just an illustration of the kinds of processes by which scientific research inches forward. I liked this paper because of how international it was -- the talk featured data from India's Chandrayaan-1, Japan's Kaguya, images and spectra from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, and radar data from orbiters and Arecibo.

In fact, the presenter is a postdoc at Arecibo, and is currently displaced from there by loss of power and water to his home thanks to hurricane Maria. So I also wanted to highlight his talk because I cannot imagine being a young researcher trying to establish my cred and having a historically awful hurricane devastate the community in which I was working. In general, I was stunned by how many Arecibo workers were at DPS and able to talk science despite what has been a traumatic couple of months for them all. If you are reading this and feel like supporting local recovery efforts, I suggest Antonio Paris' gofundme for his delivery of supplies to his home state of Utuado, and the USRA's gofundme to help Arecibo staff. Arecibo has been a major center for relief for the local area -- they've been supplying drinking water and generator power and a helicopter landing pad for relief flights, among other things.

Anyway, back to the Moon. This is the Moon. You may recognize it. But you don't usually see it from this perspective; you would have to be an astronaut to see it from this point of view. Near the top of the picture is a very pretty rayed crater named Giordano Bruno. Rays generally mean a relatively youthful crater. Over time, micrometeoroid impacts and other space weathering processes make the rays fade.

NASA / ALSJ / Emily Lakdawalla

Apollo 11 image of a nearly full Moon

One of the Apollo 11 astronauts took this photo of an almost fully illuminated Moon on July 21, 1969, during their journey home. The command module was nearly 20,000 kilometers away from the Moon at the time. The egg-shaped dark area above center is Mare Crisium. The rayed crater Giordano Bruno is near the top of the frame. Near the bottom are two small rayed craters that bracket a larger crater, Stevinus. High-sun images like this one emphasize albedo differences (like crater rays and mare basins) over topography (like crater bowls).

Another way to make crater rays fade is to look at the crater under oblique illumination. It's very hard to see the rays unless they're lit from nearly straight overhead.

NASA

Apollo 16 view of the Moon centered on Giordano Bruno crater

At the exact center of this photo is an unassuming crater with a fairly crisp rim and rumpled floor named Giordano Bruno. Thanks to oblique illumination, it's nearly impossible to see the extensive ray system that surrounds the crater.

I still find it wonderful that some of the best photos of the Moon are from the Apollo and Lunar Orbiter missions. Later missions have had fantastic cameras, but just like Viking at Mars, it's better to dig deeper into history for the prettiest wide-angle views.

Bhiravarasu's work involves looking at one feature through the lens of many different data sets. He picked Bruno because it's a very young crater (1 to 10 million years old, according to some published estimates) and therefore it's still fresh, meaning you can still see the mineralogy exposed at the surface. It lights up very prettily in Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3, pronounced "M-cubed") data captured by the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft:

ISRO / NASA / Chandrayaan-1 / courtesy Sriram S. Bhiravarasu

Multispectral views of Giordano Bruno from M3

These images of the fresh crater Giordano Bruno were all created with data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3 or "M-cubed") on India's Chandrayaan-1 orbiter. They are all false-color images representing information about the reflectance of lunar materials in the infrared portion of the spectrum.

Left image:red channel is 930 nm, green channel 1249 nm, blue channel 2018 nm. Mafic minerals appear green to yellow; feldspar-rich pixels appear pink; mature regolith appears gray.

Center image:red channel is 930 nm, green channel is 2018 nm, blue channel is 2816 nm. In this image, hydration features are highlighted yellow.

Right image:A "rock type composite" that uses spectral band information to highlight certain minerals. The red channel highlights the spectral presence of pyroxene; the green channel, spinel; and the blue channel, anorthosite.

Don't sweat it if you don't understand the caption. The point is that M3 sees the lunar surface in detail in infrared wavelengths where it's possible to diagnose the presence of certain minerals. In particular, Bhiravarasu notices hydration features in the inner flank of the crater wall and also in the ejecta blanket. "Hydration features" doesn't mean there is water or ice present, it means there are minerals that incorporate water into their crystal structure.

For the Moon, it's a relatively new thing to notice hydration features in rocks; in fact, it's M3 data that yielded the discovery of widespread hydrated minerals in 2009. In that paper by Carle Pieters and coauthors, they proposed that "the formation and retention of hydroxyl and water are ongoing surficial processes. Hydroxyl/water production processes may feed polar cold traps and make the lunar regolith a candidate source of volatiles for human exploration."

Bhiravarasu comes to a different conclusion regarding the hydration features. Here are two of his slides incorporating data from Diviner (an infrared spectrometer on Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) and Mini-RF (a radar mapper from either that mission or Chandrayaan-1). Again, my point here is not to explain the details of his work, but rather to demonstrate how we can come to deeper understanding of places in space when we can take advantage of multiple overlapping data sets.

Bhiravarasu observes that places where you can see hydration features are related to impact melt, and suggests that the water in the rocks may have come from the impactor -- that it could be a comet that made Giordano Bruno and its spectacular rays. A comet would've come in with much higher speed than an asteroid, leaving behind a spectacular ray system and a little gift of water at the impact site.

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Support enables our dedicated journalists to research deeply and bring you original space exploration articles.

from Planetary Society Blog http://ift.tt/2xCd1W6

via IFTTT

KOREASAT-5A MISSION

On Monday, October 30th at 3:34 p.m., SpaceX successfully launched the Koreasat-5A satellite from Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Following stage separation, Falcon 9’s first stage successfully landed on the “Of Course I Still Love You” droneship, stationed in the Atlantic Ocean.

Falcon 9 delivered the Koreasat-5A satellite to its targeted orbit and the satellite was deployed approximately 36 minutes after liftoff. You can watch a replay of the launch below and find more information about the mission in our press kit.

from SpaceX News http://ift.tt/2yf875D

via IFTTT

NASA Highlights Science on Next Commercial Mission to Space Station

October 30, 2017

from NASA http://ift.tt/2z5cPlE

via IFTTT

Viewing Australia's Great Sandy Desert From Space

Ohio Students to Speak with NASA Astronauts on Space Station

October 30, 2017

from NASA http://ift.tt/2z4c4JW

via IFTTT

Then vs. Now: How the Debate Over a Distant Planet in the Solar System Has Evolved

Stephanie Hamilton • October 30, 2017

Then vs. Now: How the Debate Over a Distant Planet in the Solar System Has Evolved

The region of our solar system beyond Neptune, called the “Kuiper Belt”, has seen some seriously increased attention in recent years. From discoveries of new objects nearly as big as Pluto, to the demotion of Pluto to “dwarf planet” status, to the first high-res images of Pluto from the 2015 flyby of New Horizons, everyone’s favorite Kuiper Belt Object has been at the forefront of discussions about the trans-Neptunian solar system. This post won’t focus on Pluto, however. Instead, I’ll discuss what we’ve learned about the farthest reaches of the solar system beyond Neptune in the twelve months between the 48th and 49th meetings of the American Astronomical Society Division of Planetary Science (AAS DPS).

A New Unseen Planet??

Almost two years ago, a different set of objects started competing with Pluto for the title of “the hottest topic of the outer solar system.” This set of objects includes the farthest objects we know of that orbit the Sun further out than the Kuiper Belt. They orbit with an average distance from the Sun more than 250 times the Earth-Sun distance, taking more than 4,000 years to complete a single orbit! What’s so special about these objects? Well, they appear to be grouped in a peculiar way -- their orbits all point in similar directions in physical space! This is very unexpected -- as small Kuiper Belt Objects orbit the Sun, they may experience (in)frequent gravitational interactions with Neptune or the other giant planets. Since the giant planets are so much more...well...giant, repeated interactions result in changes to the smaller object’s orbit. This “gravitational sculpting” by Neptune or the other giant planets is fairly random over timescales comparable to the age of the solar system. Thus, we would expect the orbits of objects affected by gravitational sculpting to be arranged randomly.

The curious grouping of the most distant objects we know about is the original motivation for “Planet Nine.” Planet Nine is predicted to be a “mini-Neptune” -- that is, an icy giant planet with a mass about ten times that of Earth’s. Gravitational sculpting by Planet Nine (adding to Neptune’s gravitational sculpting) could explain why the orbits of these very distant objects appear to be grouped together. There is, however, at least one more possible explanation...

First, though, let’s step it back to the 48th meeting of the AAS DPS in October 2016 (referred to as DPS48 from now on).

48th Meeting of the AAS DPS

The January 2016 proposal of Planet Nine made a giant splash in the ocean of planetary science. Even when it came time for DPS48, nearly nine months later in October 2016, the waves from that splash were still high and strong. Leading solar system astronomers dedicated months of effort toward predicting where Planet Nine might be in the sky. They devised extremely clever methods to make these predictions. One group of astronomers used inconsistencies in the distance from Earth to Saturn measured by Cassini (spoiler alert: there turned out not to be be any inconsistencies in those measurements after all...but it was a clever idea nonetheless). Another group of astronomers searched through decades of data from several different surveys just in case someone had missed an elusive distant planet in the images. All of this effort culminated in a series of talks at DPS48.

Unfortunately, no one found anything. No previously undiscovered distant planets, though all of the search efforts did turn up some quickly-moving distant brown dwarfs (objects outside of our solar system that are too small to be stars but too large to be planets). However, another idea was beginning to emerge. What if the curious grouping of very distant trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) isn’t actually real? That is, what if it is actually an observational effect purely due to where we happened to point our telescopes?

The effect I just described is known as “observational bias” -- the idea that we will preferentially discover objects on orbits that put them in a position on the sky that our telescopes are already pointed at. You might ask “well, why don’t you just point your telescopes at other spots on the sky?” Unfortunately, the solution isn’t that simple...telescope time is very expensive, so astronomers generally like to maximize that time by pointing the telescope to spots where they know they will find things. Then they must consider several other factors, such as seasonal weather patterns -- with winter comes clouds, which means that the parts of sky that are visible only during the winter are considerably less well studied and searched. As a result, determining whether the grouping of the most distant TNOs is a real effect or not becomes a very difficult problem, one that was not solved in time for DPS48.

49th Meeting of the AAS DPS

So how has the evidence for the proposed Planet Nine held up over the course of the past year? The jury is still out, actually (though the opposing sides in the debate would probably be ready to argue that with me). At the 49th meeting of the AAS DPS (referred to as DPS49 from now on), leading solar system astronomers gathered after several months of back-and-forth debate. I want to highlight two especially notable talks at DPS49. The talks summarized two studies from Summer 2017 that reached completely opposite conclusions regarding the overall importance of observational bias on the observed grouping of distant TNOs. One, conducted by the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), concluded that the observed grouping is due entirely to observational bias. The other, conducted by Dr. Mike Brown (an original proposer of Planet Nine, together with Dr. Konstantin Batygin), concluded that the observed grouping cannot be explained by observational bias. Well now, that’s confusing. Does observational bias completely explain the observed grouping of the most distant TNOs, or does it not? The truth is that we don’t know (again, cue up the arguments by both sides of this debate). We simply don’t have enough data yet!

Further complicating the debate, a number of other studies examining additional possible evidence for or against Planet Nine (aside from the grouping of the most distant TNOs) were presented at DPS49. One particularly interesting study conducted by Juliette Becker of the University of Michigan analyzed the gravitational sculpting effects of Planet Nine on the most distant TNOs over timescales comparable to the age of the solar system. The study found that many of these objects would crash into the Sun or be ejected from the solar system completely if a solar system containing only the known planets is considered. How, then, are we able to observe them today with our telescopes? If Planet Nine is added to the solar system, it can actually help offset gravitational interactions that might otherwise lead to the unfortunate demise of the TNO. The help from Planet Nine would allow these objects to “live” longer in the solar system, such that they might still be around after 4.5 billion years (i.e. the present day) to be observed with our telescopes!

The glaring problem with the study I just described is that it assumes Planet Nine exists. But again, we still don’t know whether it exists! There is some hope, though -- the proposal of a new planet in the Solar System sent astronomers to telescopes around the world in a mad dash to find it. In the process of searching for Planet Nine, they have discovered several more extremely distant TNOs that would be affected by Planet Nine’s gravity, if Planet Nine exists. So while there is no new planet to report, additional discoveries of extremely distant TNOs are the next best thing!

Toward Future Meetings of the AAS DPS

Where do we go from here? Ultimately, the conclusion that everyone involved with the Planet Nine debate can agree on is that we really need more data. We need more discoveries in the poorly-studied distant reaches of our own solar system. Only then will our picture of this region begin to fill out, like a very fuzzy television channel coming into focus. Fortunately, the world’s best astronomers are hard at work using some of the world’s best telescopes to bring the picture into focus. We’ll soon know whether Planet Nine really exists!

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Support enables our dedicated journalists to research deeply and bring you original space exploration articles.

from Planetary Society Blog http://ift.tt/2iLpJiW

via IFTTT

2017年10月29日 星期日

Orionid Meteors from Orion

Naming An Interstellar Visitor

Perhaps @IAU_org should name A/2017 U1 "Rama" - Sir Arthur C. Clarke certainly described it rather well - in 1973 #Interstellar #astronomy http://pic.twitter.com/EeLiG7m5GW

— NASA Watch (@NASAWatch) October 28, 2017

Something Visited Our Solar System From Interstellar Space, NASA

"A small, recently discovered asteroid -- or perhaps a comet -- appears to have originated from outside the solar system, coming from somewhere else in our galaxy. If so, it would be the first "interstellar object" to be observed and confirmed by astronomers. This unusual object -- for now designated A/2017 U1 -- is less than a quarter-mile (400 meters) in diameter and is moving remarkably fast. Astronomers are urgently working to point telescopes around the world and in space at this notable object."

from NASA Watch http://ift.tt/2iL2uoZ

via IFTTT

2017年10月28日 星期六

Night on a Spooky Planet

2017年10月27日 星期五

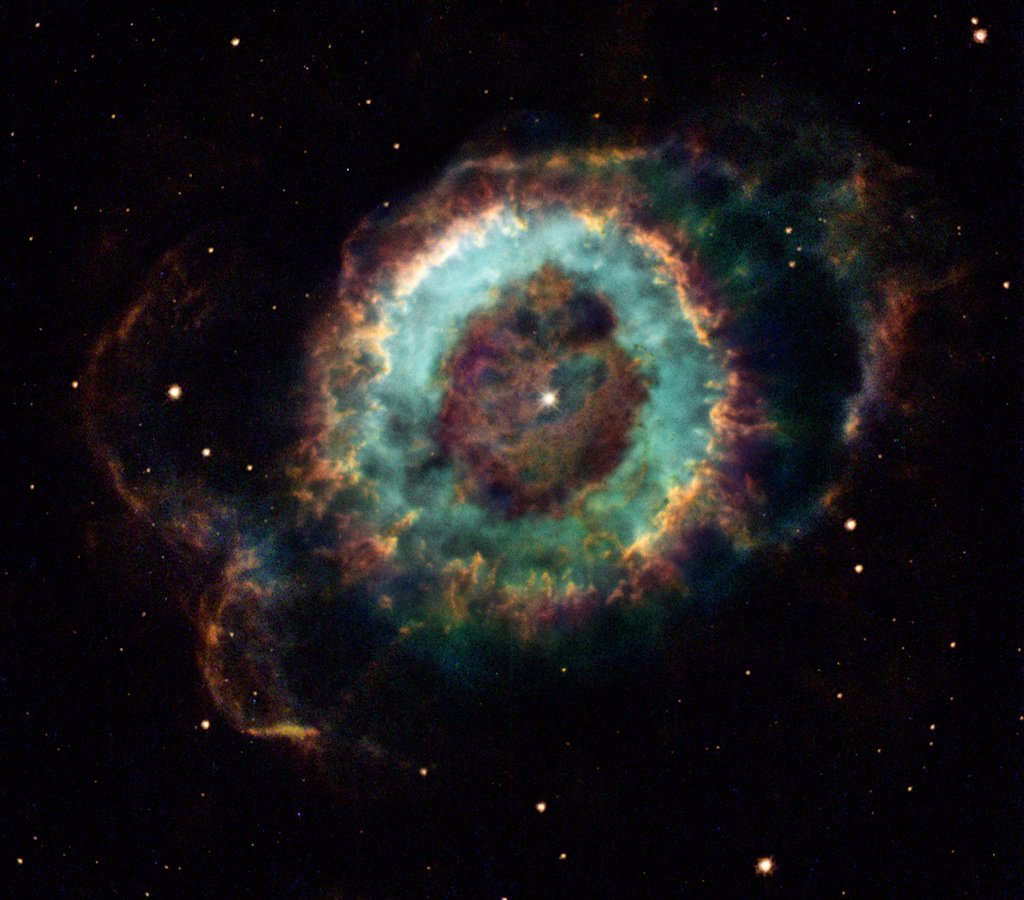

NGC 6369: The Little Ghost Nebula

Yay. Mike Griffin Finally Got A Job From Trump

Trump taps former NASA head Griffin for deputy defense role: White House

"U.S. President Donald Trump intends to nominate Michael Griffin, a former administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, as principal deputy undersecretary of defense for acquisition, technology, and logistics, the White House said on Friday."

from NASA Watch http://ift.tt/2ze2RiT

via IFTTT

Where Are All The Women In These New Space Companies?

Keith's note: I just got this advertising email from Axiom Space titled "The Promise of Human Spaceflight for Investors" bragging about Axiom being featured in lots of high visibility magazines. The email is slick, with nice portraits of the Axiom team - the faces they apparently want investors, the public, and the news media to see. I am certain that everyone is highly skilled, etc. But as I scrolled down this very long email something struck me: its all 50-something males. After eight of their smiling faces scrolled by there was a single woman - at the bottom of the list. Eight males, one female. I guess this is the optics that Axiom Space wants to put forward for their vision of the future human spaceflight.

I asked Axiom about this. Amir Blackman replied "Other than the two founders, all team members are listed in alphabetical order. Gender is not a consideration in our hiring process. We are an equal opportunity employer and seek out team members based on their qualifications and experience." Right. Like I said eight males, one female.

Here is a larger version of their email (I thought I'd give them some free PR).

from NASA Watch http://ift.tt/2gI3DJC

via IFTTT

Its Time For The Semiannual SLS Launch Date Slip

SLS rocket advancing, but its launch date may slip to 2020, Ars Technica

"NASA will soon set a new date for the maiden flight of its massive Space Launch System rocket, which will send the Orion spacecraft on a test flight around the Moon. Previously, this flight had been scheduled for 2018, but NASA officials acknowledged earlier this year that the launch date would slip into 2019."

from NASA Watch http://ift.tt/2xtXbNp

via IFTTT

Hubble Digs into Cosmic Archaeology

Explore spinnable Saturn and Jupiter moons with Google Maps

Emily Lakdawalla • October 27, 2017

Explore spinnable Saturn and Jupiter moons with Google Maps

Last week, Google Maps released several new map products that allow you to see the locations of named features on many solar system planets and non-planets. The mapped worlds include Mercury, Venus, our own Moon, Mars, Ceres, and Pluto (but not Charon, sadly). Three out of four large Jupiter moons make the list: Io, Europa, and Ganymede, but not Callisto. All but one of the round Saturnian moons is listed: Mimas, Enceladus, but not Tethys for some reason, Dione, Rhea, Titan, and Iapetus. It's handy to be able to rotate the moons to match the aspects of space photos, though I wish the angle of illumination could be changed. But these aren't true 3D shape models, they're just maps stretched over spheres.

I didn't post about this last week because maps for almost half of the worlds didn't align properly with the features. That problem has now been fixed. Google hadn't been aware that there's no common convention for how you center simple cylindrical maps, and some of the maps they'd been given were centered at 0 degrees longitude, while others were centered at 180. Ganymede, Mimas, Enceladus, and several others all had the map names perfectly opposite the globes to where the features were actually located. I'm bemused that there were a lot of Web articles about the Google maps last week that pointed to the new service but said the maps were wrong, pointing to my tweet about it. Serious question to the space journalists who did that: why would you tell your readers about a set of maps that are wrong? I waited until I was sure they'd been fixed before posting this article.

The maps are a neat tool that I expect to make a lot of use of, but they're fairly simple so have limits. They aren't very smart about linear features; one place name has to do for the entire linear feature, and the place name isn't oriented parallel to the linear feature, so where there are a lot of such features in one place, like on Europa, it can be tough to figure out which place name corresponds to which line. The maps intelligently display names for only the largest features when you're zoomed out, which is usually useful, except when it comes to small craters with big ray systems. They may be highly visible features even at great distance, but their names don't show up unless you zoom way in. Finally, polar features on the map of Enceladus don't quite fall in the correct spots, I think because the map projection assumed Enceladus was spherical when it's actually noticeably flattened. For real detail in maps, it's better to look at the ones created by the United States Geological Survey, which are much more reliable. I just posted all their maps of Saturnian moons to our image library. But for spinning globes and matching them to photos, the new Google maps are a valuable service, and I'm glad it's here!

Read more: Enceladus, Dione, mapping, Titan, Mercury, Rhea, Saturn's small moons, Iapetus, global views, Saturn's moons, asteroid 1 Ceres, Mimas, Jupiter's moons, Io, Europa, Pluto, Ganymede, Venus, the Moon, Mars

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Support enables our dedicated journalists to research deeply and bring you original space exploration articles.

from Planetary Society Blog http://ift.tt/2iHtea9

via IFTTT

Prolific Earth Gravity Satellites End Science Mission

October 27, 2017

from NASA http://ift.tt/2zbuBVn

via IFTTT

Here's how engineers closed out LightSail 2 for flight

Jason Davis • October 27, 2017

Here's how engineers closed out LightSail 2 for flight

Last month, engineers reconfigured The Planetary Society's LightSail 2 spacecraft into its flight-ready state for what is likely to be the last time. It's a big milestone for the program; after years of effort dating back to 2009, work on the CubeSat is finally finished.

The procedure to button up LightSail is called closeout. The team sets the spacecraft's software to start the mission on the next boot, and physically secures all deployable structures including the antenna and solar panels.

LightSail 2 spent 2017 in a hurry-up-and-wait mode while launch dates remained fuzzy for SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket. The uncertainty provided an opportunity to perform more tests and tweaks, with the knowledge that the order to ship the spacecraft could come at any time.

Launch is currently scheduled for no earlier than April 30, 2018. But that could always change, based on the timing of one or possibly two Falcon Heavy flights ahead of the STP-2 mission for the U.S. Air Force, which will carry LightSail 2 and its partner spacecraft, Prox-1, as secondary payloads.

LightSail's final path to launch starts at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, with integration into a spring-loaded deployer called a P-POD. Once LightSail 2 is inside the P-POD, its battery can't be charged, so the team is currently storing the spacecraft at Ecliptic Enterprises Corporation in Pasadena, where its power levels can be monitored and occasionally topped off. After P-POD integration, LightSail 2 ships to the Air Force Research Laboratory in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for installation aboard Prox-1.

In the meantime, engineers formally closed out the spacecraft. Roughly speaking, closeout is the last time you fiddle with a spacecraft before launch. It's sort of like walking through your house one last time before vacation; you might set the thermostat for your absence, turn on the alarm and lock the doors. At that point, you aren't expecting to go back inside.

Closeouts must be done carefully, and not just because they determine whether things will go well on launch day. Case in point: NASA's TDRS-M satellite recently had a nasty run-in with a crane during closeout, delaying the mission.

At just 33 steps long, the LightSail 2 closeout was far from dramatic, but each procedure was carefully documented by Ecliptic engineer Stephanie Wong. Here's a condensed version of the closeout procedure, with explanations and photos showing how LightSail 2 was buttoned up for flight.

Verify LS2 has been flashed before antenna is stowed.

"Flashing" the software clears all files on the flight computer, such as old telemetry logs and pictures taken during testing. It's like reinstalling the operating system on your computer, giving it a clean, out-of-the-box appearance. There's even a screenshot taken to verify the correct software version was installed.

Rotate LS2 with the -Y panel facing up. Remove all internal blue film. Inspect external -Y panel. Inspect internal -Y panel. Restrain panel.

These steps are repeated for all four deployable solar panels, which comprise the X and Y axes of the spacecraft. The blue film protects the solar panels from damage the way new smartphones come wrapped in clear stickers and plastic. At this point, everything on LightSail 2 has been tested as working, so the closeout's main purpose is physically documenting how the spacecraft looked before flight, while making sure nothing is obviously awry.

Rotate LS2 to view the +Z panel. Inspect external +Z panel.

The +Z panel is what we think of as the bottom of the spacecraft. It faces Earth before solar sail deployment and is equipped with laser ranging reflectors to allow ground observers to precisely measure the spacecraft's position. Notice the antenna is still deployed here; the +Z panel comes off in a future step to fix that.

Rotate LS2 to view the -Z panel. Inspect external -Z panel.

This end of the spacecraft faces the Sun when solar sailing thrust is active.

Rotate LS2 so the antenna is facing upwards. Unscrew the four main board screws and two antenna housing screws. Tie new spectraline, check the NiCr wire and re-assemble the antenna housing.

This a crucial step. Spectraline is the fishing line-like wire that holds the solar panels shut. They loop through a nickel-chromium coil that heats up and burns through the spectraline, allowing the solar panels to hinge open. There are two NiCr circuits for redundancy, because if the solar panels don't open, the solar sail can't deploy, and the mission will fail.

The antenna is coiled into a loop, and its hinged door is pulled shut by another piece of spectraline, which runs through a second NiCr heating loop.

Spot bond NiCr wire and any necessary areas. Let cure.

Delicate pieces of LightSail 2 that could vibrate and break during launch are covered with a grey, epoxy-like substance known as staking compound. This includes screws and exposed wire connections.

Screw the antenna assembly back onto the main panel. Then screw the main panel back to the spacecraft. Ensure the ground wire is under one of the screws. Tighten and stake. Let cure at room temperature. After 24 hours, inspect spacecraft.

After putting the antenna and +Z panel back on LightSail 2, its remaining screws are staked and given 24 hours to cure.

Store appropriately for transport.

That's pretty much it! The next stop for LightSail 2 is Cal Poly.

The spacecraft is now closed out and in storage at Ecliptic. The battery will be topped off again before transport, the blue film on the exterior solar panels will be removed, and LightSail 2 will be ready for P-POD integration.

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Support enables our dedicated journalists to research deeply and bring you original space exploration articles.

from Planetary Society Blog http://ift.tt/2za1O3q

via IFTTT