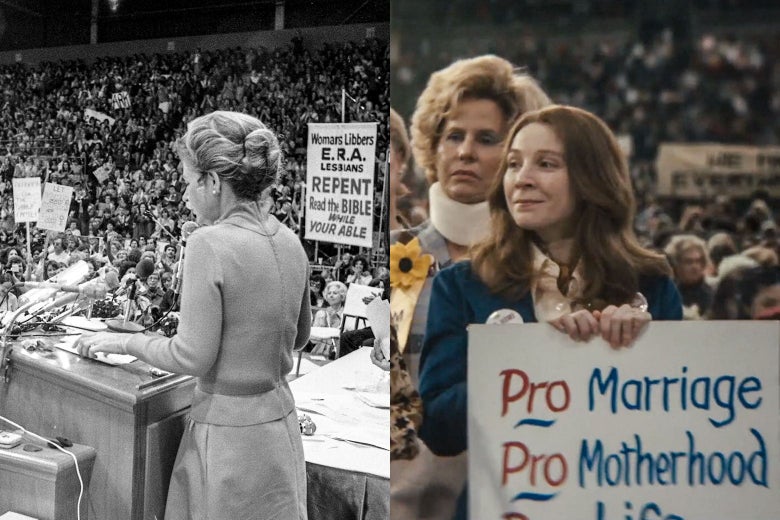

Archival photograph from the National Women’s Conference in 1977 beside a still from Mrs. America.

Photo Illustration by Slate. Photos by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images and screengrab from FX Networks.

In Episode 8 of Mrs. America, the conservative Eagle Forum leaders travel to Houston to challenge Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and the other feminist leaders at the National Women’s Conference. Having rustled up several hundred conservative delegates through their grassroots organizing, the anti–Equal Rights Amendment activists arrive ready for battle, but things don’t exactly go as planned.

As we’ve noted in our articles on the historical accuracy of each of the previous seven episodes, the character of Alice (Sarah Paulson) is fictional, so we were not able to fact-check whether any conservative housewives attending the convention accidentally got high, sang Woody Guthrie with a group of hippie feminists, and ate food out of the garbage. However, the National Women’s Conference itself was very real. Below, we compare the show’s depiction of the event to photos, contemporary documents, and other historical accounts.

The National Women’s ConferenceArchival photograph of the stage at the National Women’s Conference in 1977 above a still from Mrs. America.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images and screengrab from FX Networks.

The National Women’s Conference is depicted as a huge, bustling, and somewhat chaotic event, and indeed the real National Women’s Conference, held from Nov. 18 to 21, 1977, was—as we hear NBC’s Tom Brokaw announce in a news clip excerpted in the episode—“the largest gathering of American women ever held,” with about 20,000 people, mostly women, in attendance.

When Alice and Pamela (Kayli Carter) arrive in Houston, their hotel is mobbed, and they are told that all the rooms have been overbooked. Awkwardly, they are forced to share a room with Audrey Rowe Colom (Melissa Joyner) and her daughter. (Audrey Rowe Colom was indeed one of the real-life leaders of the pro-ERA movement, a Republican who became chairwoman of the National Women’s Political Caucus.) While Alice and Pamela are both fictional characters, the circumstances match up with real accounts from the conference. According to the Texas State Historical Association, “A combination of overbooked hotels and the late departure of participants at previous conferences led to a prolonged delay in participants receiving accommodations.” An article in the Washington Post described the lobby of the Hyatt Regency on Nov. 18 being inundated with “more than 500 people … waiting in line to register” for the conference and large swarms of women “lugging their suitcases, waiting for room assignments, singing songs and making new friends.” One conservative delegate from Missouri, Dallas Higgins (wife of KKK “grand dragon” George Higgins Jr.) told the Clarion-Ledger that week that she was unable to get a private hotel room and feared they would be arranging her to room with a “black lesbian.”

As the show depicts, the crowd included a politically and racially diverse array of women, represented by some 2,000 delegates from nearly every walk of American life. The government’s official report about the conference recalls of the delegates:

They were of all colors, cultures, and heritages: whites, blacks, Asian Americans, Hawaiians, Samoans, Eskimos, Aleuts, American Indians from many different tribes, and Hispanics of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Latin American origin. They were of all occupations: secretaries, teachers, nuns, nurses, lawyers, doctors, ministers, factory workers, farmers, waitresses, students, scientists, migrant workers, Members of Congress, mayors, business owners, and at least one astrologer.

In an evocative 1977 article in the New York Times, the writer Anne Taylor Fleming describes the atmosphere of one hotel lobby during the conference, and it’s much like on Mrs. America:

Everywhere there were women, mostly middle‐aged, middle‐class: club women, church women, union women, wearing buttons like “How Dare You Assume I’d Rather Be Young?” or “A.A.U.W. for E.R.A.”; women of eclectic causes and eclectic vanities; women in muumuus, tweed suits, gaucho pants; women drinking, laughing, talking; women doing grown‐up things and exhilarated to be doing them, things like tipping waiters, carrying suitcases, lobbying and caucusing to all hours of the night; women exhilarated, too, by their sexual indefiniteness, their sexual immunity in this temporary world without men.

The staging and set design, too, is quite accurate. Many of the visual details—including the conference signs, logos, staging, and even buttons—are pulled directly from photos of the event.

The TorchBella Abzug, Billie Jean King, Betty Friedan, and others carrying the torch that signaled the start of the 1977 National Women’s Conference.

National Commission for the Observance of the International Women’s Year/PhotoQuest/Getty Images

As the opening shots of the episode depict, the conference was launched by the lighting of a torch that was carried to Houston all the way from Seneca Falls, New York, where the first women’s rights convention was held more than a century earlier, by more than 2,000 women, including pro tennis player Billie Jean King, in a dramatic gesture of national bipartisan support for the event. As PBS notes, a “Declaration of Sentiments” written by Maya Angelou and “signed by thousands” also “accompanied the torchbearers, who presented it to current and former first ladies Rosalyn Carter, Betty Ford and Lady Bird Johnson at the conference’s opening ceremony.”

Rosemary Thomson Steps Into the SpotlightRosemary Thomson and Melanie Lynskey as Rosemary Thomson in Mrs. America.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Denver Post via Getty Images and FX for Hulu.

In this episode, with Phyllis Schlafly remaining in the background for political reasons, Rosemary Thomson leads the charge of conservative delegates at the conference. As head of the Illinois chapter of the Eagle Forum and an Illinois delegate, Thomson indeed was a significant presence at the conference, where she helped to write an anti-ERA resolution, and as shown in the episode, there really were fights about how much the anti-ERA side should be allowed to speak. Anti-ERA representatives including Thomson claimed they were being silenced while conference leaders insisted they were going the extra mile to ensure everyone would be heard. As happens in the show, Bella Abzug even came to the defense of the pro-life delegates, insisting that the minority also has the right to speak. As for Thomson’s anti-abortion speech, we weren’t able to find any record of it, though Thomson was certainly anti-aborition. Finally, near the end of the episode, Thomson expresses her intention to write a book entitled The Price of Liberty. She did, in fact, write that book, which was published the following June.

Betty Friedan’s Stand for Gay RightsBetty Friedan beside Tracey Ullman as Betty Friedan on Mrs. America.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by B. Friedan/MPI/Getty Images and FX.

In a stirring scene near the end of the episode, Betty Friedan (Tracey Ullman) rises to offer words of solidarity and support for the sexual preference recommendation proposed by Jean O’Leary, despite the fact that it’s among the most controversial proposals. Friedan did in fact attend the conference and, despite her reputation for being unsupportive of gay rights, endorsed the plank. Her words in the episode are pulled nearly verbatim from Friedan’s actual comments, though they were somewhat abbreviated:

I am known to be violently opposed to the lesbian issue. As someone who has grown up in Middle America and as someone who has loved men too well, I have had trouble with this issue. Now my priority is passing the ERA. And because there is nothing in that that will give any protection to homosexuals, I believe we must help the women who are lesbians.

According to historian Doreen J. Mattingly, the ensuing celebration was nearly identical to the one depicted in the episode, down to the fact that “hundreds of balloons stenciled with ‘We Are Everywhere’ were released in jubilation.” In a recent essay, historian Marjorie Spruill Wheeler recalled the joyous moment similarly, describing the crowd breaking out into song, just as happens on the show: “Spontaneously, and as cameras rolled, delegates rose, clasped hands, and began singing, ‘We Shall Overcome’—for many, the emotional highlight of the conference.”

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/2XhxugS

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言