Jess Mollerup • May 11, 2020

Visiting Perseverance During Its Final Week at JPL

The Planetary Society is an education and outreach partner for the Mastcam-Z instrument on NASA's Perseverance rover. We feature stories from the team sending this cutting-edge camera system to Mars.

A hum of excitement fills the air as I follow the other members of our research team into a narrow, white hallway lined with large bay windows. As we crowd into the small room, I peer out at the Spacecraft Assembly Facility below us. I watch as a dozen or so engineers, all dressed in identical white “bunny suits,” shuffle around the clean room. From my bird’s-eye view in the High Bay, it looks like a choreographed dance. I stand there mesmerized as the team meticulously unfurls a giant sheet of silver and drapes it over the Perseverance rover’s cruise stage. Suddenly, it all feels so real. We are once again sending a robot to another planet.

Jess Mollerup

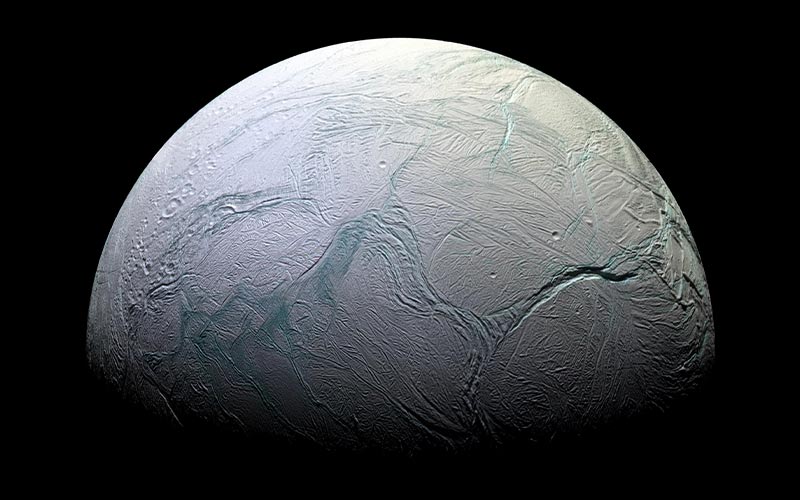

The Perseverance Rover and Cruise Stage in the High Bay

Engineers in their clean-room “bunny suits” perform final tests on the Perseverance rover in the Spacecraft Assembly Facility at JPL as seen through the window of the viewing gallery on 6 January 2020. To the left, the engineers lay out a silver sheet before placing it over the cruise stage (seen behind) as they prepare to send it to the launch site in Florida the following week.

In January 2020, my research team, composed of undergraduate and graduate physics and geology students from Western Washington University, experienced the opportunity of a lifetime. We traveled to Pasadena, California to meet other scientists working on the Mars 2020 mission team and to set eyes on the rover that will leave Earth in July to begin its journey to the beautiful Red Planet—Mars.

There’s something magical about being involved in space missions. Back at our lab at WWU, our team spends our days looking through the scientific “eyes” of the Curiosity rover, analyzing the dusty, red images from the surface of a planet that is many millions of miles away from us. My research often involves working in a dark basement lab collecting reflectance spectroscopy data of Mars analog rocks (rocks from Earth that are similar in composition and environment to the rocks that Curiosity encounters) and quantifying what these rocks would look like through the wavelengths of Curiosity’s Mastcam cameras. More and more, I’m also pondering how these rocks would look to the Mars 2020 rover’s Mastcam-Z cameras.

When staring at a computer screen and studying the spectra of rocks collected from various locations across our own planet, it can be easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. Why are we doing this? What are we looking for?

When our team arrived at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), I was immediately reminded of why my research matters. I have the opportunity to take part in some of the most incredible work in which humankind has ever engaged. I get to contribute to sending a rover through the vacuum of space to an entirely different planet in search of answers about the history and future of our solar system. I'm able to help answer an important question—are we alone in the universe?

Faith Haney

WWU Research Group in the High Bay

The current research group and alumni from Western Washington University who work on the Curiosity and/or Perseverance rover missions gather in the viewing gallery of the Spacecraft Assembly Facility at JPL. Back row from left to right: Cory Hughes, Sam Condon, Isabella Seppi, Darian Dixon, Mason Starr, Melissa Rice, Jess Mollerup. Front row from left to right: Kristiana Lapo, Katherine Winchell (holding a scale model of Mastcam-Z), Tina Seeger, Amanda Rudolph.

Looking into the High Bay, watching the dance of the white bunny suits, and listening to Mastcam-Z Deputy Principal Investigator Justin Maki from JPL explain how Perseverance’s cameras will allow us to see the surface of Mars, I was filled with a sense of awe and wonder.

Allow me to back up for a moment and explain how I got here. I'm currently an undergraduate physics major at WWU (soon to be a graduate student in geology), where I use reflectance spectroscopy to study rocks on Earth and Mars. One of my current research projects involves validating some of the data that Mastcam-Z collected during calibration. This trip to Pasadena wasn’t solely to see the rover; it was also an opportunity to meet and collaborate with other planetary scientists.

Our day had begun with a visit to Professor Bethany Ehlmann’s lab at Caltech (Bethany is a Mastcam-Z and SHERLOC co-investigator on Mars 2020), where Lab Manager Rebecca Greenberger helped us acquire spectroscopy data of some of the same rock targets that Mastcam-Z had photographed during its calibration activities. I was accompanied by a few fellow research students and my adviser, Melissa Rice, who is a co-investigator for the Mastcam-Z mission team. Emily Lakdawalla of The Planetary Society also came by the lab since some of the targets included intricate, artistic arrangements of rocks and minerals that she compiled from her personal collections. We spent the morning acquiring data using a hyperspectral camera, which can see the same wavelengths that Mastcam-Z will use at a much higher spatial resolution than the spectrometer in our WWU lab.

ASU/MSSS and Faith Haney

Rock Targets Studied for Mastcam-Z's Instrument Calibration

On the left is a cropped image taken by the left Mastcam-Z camera during the instrument’s calibration activities at Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego. The targets mounted to this “geoboard” include Mars analog rocks, color standards, geometric targets, and models of the real Mastcam-Z calibration targets as well as several artistic rock mosaics and the LEGO Mastcam-Z logo made by Emily Lakdawalla. On the right, author Jess Mollerup prepares to image one of the rock mosaics (a “stratigraphic column”) with the hyperspectral camera at Caltech.

As I watched the colorful tray of rocks sweep back and forth across the optical bench, allowing the imager to collect the light reflected from the samples’ jagged surfaces, I could feel the anticipation growing within me. Later that day, I would get to see the actual Mastcam-Z instrument —the cameras mounted on the Perseverance rover’s mast that will soon provide us with the first images from within Jezero crater.

A few hours later, we congregated in the lobby of the JPL visitor center while waiting for Systems Engineer Justin Foley, who would act as our tour guide for most of the day. Our team was joined by a few WWU alumni, some of whom are now working on Mastcam-Z as mission specialists for Malin Space Science Systems and one of whom is pursuing a PhD studying data from the Curiosity rover. We found ourselves having a research team family reunion as we chatted over coffee and shared our mutual excitement about getting to see the Mars 2020 rover (which was soon to be named Perseverance) in person.

Before heading to the High Bay in the Spacecraft Assembly Facility, we first stopped at the von Karman Visitor Center, where we viewed full-scale spacecraft models of Voyager and Galileo. As I walked through the museum, passing below images of the planets and reading about the history of the spacecraft that began their journeys at JPL, it felt like I was walking back in time, watching the magnificence of human curiosity and achievement unfold before me.

My physics-loving brain listened with delight as Foley explained to us how the ring of 11 motors encircling the Explorer 1 satellite were spun up 10 minutes before launch, spinning around at 750 revolutions per minute as a means of stabilizing the thrust of the clustered motors that would take the United States’ first satellite into space.

Jess Mollerup

At the JPL Museum, Justin Foley Explains Explorer 1's Design

JPL Systems Engineer Justin Foley (left) answers students' questions about the ring of motors encircling the Explorer 1 satellite. Explorer 1, which was designed and built at JPL over the course of only 3 months, was the first satellite launched into space by the United States on 31 January 1958.

After exploring the museum, we made our way to the highlight of our trip: the Spacecraft Assembly Facility High Bay. From the narrow corridor of the viewing gallery, I finally laid my eyes on the Perseverance rover.

It’s difficult to describe the magnitude of this experience and find words to express the feeling I encountered when I looked down at the robot that would spend its days traversing the dusty terrain of a planet that no human has ever touched. There’s something so surreal and invigorating about being in the same room as the rover we are sending to another planet.

Jess Mollerup

Mastcam-Z Lego Logo in the High Bay

A representation of the Mastcam-Z instrument team logo was made out of LEGO bricks, seen here in the viewing gallery of JPL’s Spacecraft Assembly Facility, where the Perseverance rover is being built and tested below. Mastcam-Z took images of this same LEGO logo during its calibration activities.

We crowded around as Maki presented a scale model of a Mastcam-Z camera, showing us where the 8 narrowband filters were housed and explaining the intricacies of how they worked. As I glanced around the room, I couldn’t help but smile as I watched my friends and colleagues point at various objects on the assembly floor, giddy with excitement as they took selfies with the rover and Emily Lakdawalla’s Mastcam-Z LEGO logo.

The remainder of our tour included other engineering buildings, instrument testing facilities, and the dark "mission control" room where the Deep Space Network operates. We also engaged in invaluable conversations with other mission scientists.

After an exciting yet exhausting day spent trekking up and down the steep hills of JPL’s campus, our research team headed to The Planetary Society's headquarters, which was closed for the day, but invitations had been extended to us for an after-hours dinner and a private tour of its offices.

The walls were decorated with memorabilia from space missions past, including computer chips the size of textbooks that could now fit into a space smaller than a fingernail, juxtaposed with some of the latest feats of human innovation, like a massive silver sail that is propelled through space by light. I had never been inside an office like this before—a workplace of my space nerd dreams!

As we wandered the halls in anticipation of dinner, we enjoyed the opportunity to meet some of the incredible folks at The Planetary Society, including CEO Bill Nye, who gave us an impromptu lecture about his days in engineering school and demonstrated how to make mathematical computations on a 6-foot-long slide rule.

That evening, we gathered over food and drinks to share stories: stories about our lives as scientists, including both the excitement and the frustration of the work we do, as well as stories about ourselves—what we love, what makes us laugh, and what drives and inspires us.

It’s in these stories—these moments of vicarious experience—that I understand the reason I really love my work. It’s not just the science but the scientists. It’s our shared curiosity about the universe, our shared passion to push the boundaries of understanding, and our shared joy over a robot that sings happy birthday to itself.

I returned home not only with new data for my research and stories to share with my peers but entrenched in a deeper appreciation for scientific collaboration and for the coalescing of our differing experiences and expertise, without which we wouldn’t be sending instruments, rovers, or humans into space.

Mars - Planetary Society Blog Cut from WWU Video on Vimeo.

Let's Change the World

Become a member of The Planetary Society and together we will create the future of space exploration.

The Planetary Fund

Help advance robotic and human space exploration, defend our planet, and search for life.

from Planetary Society Blog https://ift.tt/2YSPIYI

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言