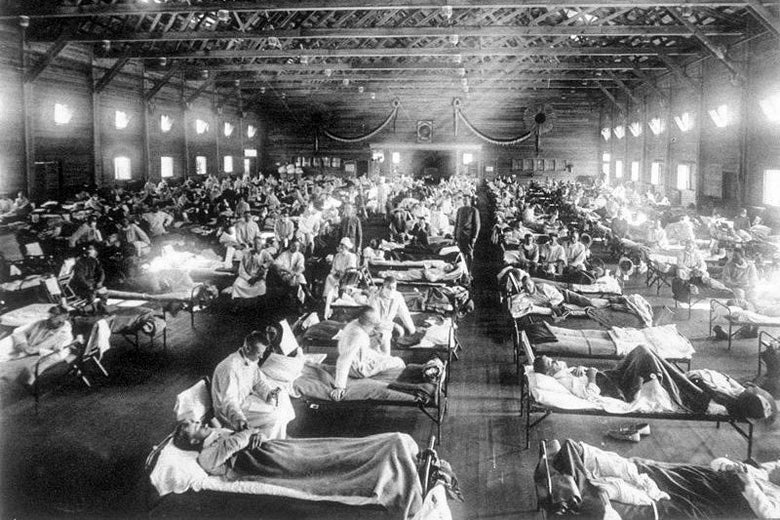

Camp Funston.

U.S. Army/Wikipedia/Public Domain

My first hot flash hit inside the San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, where I’d traveled from Wisconsin to see the crypt of Davy Crockett. There was a baptism there that day, and a white-gowned baby howled when the priest cupped holy water over its head. I was jealous and wanted cool water splashed on me. My next feverish wave shoved me outside, to a pharmacy down the street, where a cheap thermometer told me I was running a tick high. The next four hours, wandering among the Alamo ghosts, mostly remain a blur.

These were my first symptoms, I think. It’s impossible to claw through the fog of a weekslong illness and pinpoint its initial strike. I could have caught it the next day when an airport employee coughed on my arm. I rushed to the bathroom, stripped my shirt, and furiously scrubbed my limbs up to the elbow. Two sinks over, a guy in a slick golf shirt sneered. I don’t usually bathe here, I wanted to tell him. A fit of hypochondria.

The following week, fleeting spells came and went, chills, a sweaty forehead, low-grade fever, odd body aches, weird, single-burst coughs.

My great-grandparents’ letters detail the origin of the 1918 flu pandemic in real time .

Jeff Snowbarger

Hutchinson, Kansas

July 1918

Families, friends, and lovers packed the depot platform. They’d flocked in autos, surreys, and buckboard wagons to bid their boys farewell. With winter wheat harvest complete, the young men were off to war. No one knew how long the upheaval would last. Under a merciless Kansas sun, the press of bodies gripped Edward so tightly he nearly lost his suitcase. Mary squeezed at his side, but there wasn’t enough wiggle room for Edward to wrap his free arm around her. Despite their monthlong engagement, the lovers did not kiss goodbye.

The letters he wrote to the woman he was courting, my great-grandmother, detail the origins of the pandemic in real time.

Edward and Mary were my great-grandparents. Edward was 24, Mary 22. Both had been reared in devout homes steeped in Scripture and song. Their lives revolved on an axis of hard work and holiness revival. To them, chores and prayer were equal acts of worship. After he arrived at Camp Funston, the barrack boys couldn’t believe Edward had never kissed a girl. According to Mary, the nosy soldiers’ “indulgences were disgusting.”

During their three-year courtship, the pair exchanged hundreds of letters, which my grandfather saved in a beat-up steamer trunk that serves as our family archives. Edward lived on a farm 30 miles west of Hutchinson, while Mary’s folks bounced around town and finally settled in an orchard house on the outskirts of the small prairie city. Even through the days when they regularly met in person, their correspondence rarely stalled longer than a few days. Like the prairie that raised them, their penmanship was free of flourish, elegant in its plainness. Naïveté leaps off the page. Both were smitten—by each other, by God. As Mary wrote in June of 1918:

I wonder what you are doing this hot afternoon. I don’t see how you could endure it out in the field. … I picked cherries for three hours this morning, also picked a gallon of June berries before dinner. … I’m glad that Jesus can keep us even in hot weather.

At the depot that July, they had no clue what lay in store. No one forecast the long black cloud bearing down.

Six days after the baptism, a spasm gripped my chest, a brief lung squeeze familiar to asthmatics. I puffed my emergency inhaler and soon felt fine. For several days, the spasms returned, growing in frequency and punch. By now the nation was at war—the coronavirus had shut local schools, canceled March Madness, and begun overwhelming hospital beds. I wondered if my symptoms were simply manifestations of stress, the way our bodies sponge anxiety, uncertainty, until it dwells urchinlike inside us. Had the global panic attack hit me? Twelve days after the baptism, huffing, heart pounding, dizzy, I drove to the ER not knowing if or when I’d see my wife and kids again.

Camp Funston anchored a bend at the head of “the Kaw,” or Kansas River. Just west of camp, the Smoky Hill and Republican rivers joined to form the muddy flow that skirted Funston’s grid of long, rectangular barracks, chow halls, hospitals, parade grounds, quartermaster stations, classrooms, libraries, and company headquarters. Treeless hills nested the encampment, grassy oblong mounds of layered limestone and chert, otherwise known as the Flint Hills, the most dramatic topographical ripple splitting Kansas.

During the American mobilization for World War I, Camp Funston served as one of 16 Army training posts scattered across the nation. Here, the U.S. Army drilled enlisted and conscripted men, boys mostly, in marksmanship, tent pitching, and “practical bayonet combat.” On the flyleaf of his Infantry Drill Regulations manual, Edward wrote:

My General Orders are:

I. To take charge of this post and all gov’t property in view.

II. To walk my post in a military manner, keeping always on the alert and observing everything …

My great-grandfather.

Jeff Snowbarger

At any given time, 30,000 to 50,000 people swarmed the military grounds. For every dinner shift, an ocean of coffee was boiled, a range of cattle consumed, a mountain of potatoes peeled. Sleeping halls held 150 beds so entire companies could bunk together. The claustrophobic quarters readied soldiers’ minds to be sardined into boxcars, transport holds, and, eventually, trenches gouged in foreign soil. Most Midwestern boys had never experienced this unnatural density of humanity.

When my great-grandfather arrived, Camp Funston had already proved to be a breeding ground for disease. The early months of 1918 saw local outbreaks of smallpox, spinal meningitis, measles, “lump jaw” or mumps, scarlet fever, diphtheria, tuberculosis, typhoid, and cholera, not to mention the mostly unmentioned venereal or “social diseases,” which camp officers blamed on the “influences” of “immoral and diseased women” from Kansas City and Topeka. As an adherent to the tenets of Christian holiness, Edward avoided this final plague. The exuberant script on his discharge letter deemed his character Excellent. God was Edward’s only true lover. Twenty-four and kissless, a green enlistee in worldly war, he believed as it reads in Leviticus: “Therefore, having these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from all defilement of flesh and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God.” Shortly after his welcome to Funston, Edward discovered God was not the only invisible presence to fear.

My nurse and doctor wore disposable smocks and gloves, face masks taped to their cheeks, and plastic shields like riot police. My oxygen levels were good; blood pressure high; 20 breaths a minute, also high. My flu test came back negative; chest x-rays looked clean. Diagnosis: upper respiratory infection with cough. The nurse who administered the COVID test warned it wouldn’t be pleasant—the nasal swab felt like a sapling being screwed into my brain. Labs are swamped, she said. Results won’t arrive for a week or more.

I was told to rest and hydrate; acetaminophen should help the aches; take your inhaler as needed; and come back immediately if your symptoms worsen. That night, back home, my fever spiked. My chest felt tighter than ever and waves of fever froze then broiled my bones. I quarantined myself in a side bedroom and woke the next morning tangled in wet sheets. The 10 steps to the bathroom were a woozy mountain climb.

Mid-August, Mary wrote:

Think I hear someone in Mr. Coleman’s melon patch. … Glad you are getting acquainted with some real Christians with whom you can associate. … I am so thankful to Jesus and all he means to my unworthy heart. … [T]he Eds’ brought their “Edison Phonograph” out here Sunday.

Simplicities filled Mary’s days: washing, milking, Papa’s threshing and apple picking, neighbor visits, piano lessons, prayer meetings, Scripture study, helping “the girls read Caesar.” Her letters plainly convey life did not halt once her fiancé stomped off to war.

Papa feels somewhat encouraged by his apples.

I must get the cow in and milk. So will have to close.

Our prayers are with you boys and we just want God to have His way.

Her dispatches to Edward read as if their casual conversations never paused, as if their faith in God and each other was sufficient to make her unseen, unreachable lover feel a sofa pillow away. “I don’t suppose you were very hungry for sausage by the time you had ground such a large amount. Were you?” More seasoned at culling heifers, tilling with draft teams, and sawing stovewood, Edward struggled through camp kitchen duty, and Mary relished small moments where experience gave her the upper hand.

By late September, another seeming triviality visits her page: “[M]amma read in the paper that it was a false alarm and that there wasn’t any Influenza in the state. So my hopes rose again.” She was responding to Edward’s news that Camp Funston was being quarantined and would impede her desire to travel his way and spend an afternoon picnicking, swapping dreams, parting in prayer.

This wasn’t Funston’s first medical lockdown of the year. Partial and individual quarantines and had been issued for spinal meningitis, smallpox, scarlet fever, German measles, influenza, and pneumonia. Quarantine restrictions limited travel on and off base and closed the camp to outside visitors. Night guards, posted on every street in camp, operated under strict orders to report any sign of sickness. Medical officers isolated symptomatic individuals, often ordering men to report to one of two canvas-roofed field hospitals erected a safe distance from the main hive of operation. Separate convalescent camps were built to house men who’d simply come in contact with a confirmed case of scarlet fever or measles. Other outbreaks forced command to sequester entire barracks to prevent disease from ravaging the wider camp.

Most soldiers took the separation measures in stride. Meningitis, scarlet fever, and measles were equally miserable to endure as they were communicable. Many relished the downtime, as quarantine offered a respite from hard labor for the first time in their lives. Others felt the ward walls pressing in: The snake squeeze of confinement made them itch, the un-American stricture of movement. Paranoia drove a handful insane.

“Much Ado About Nothing,” a nearby newspaper explained to its readers. “That’s what some people call all the care in vaccination and establishing quarantine and fumigating, but it is better to have the ‘much ado’ and ‘nothing’ serious as a result than to have no ado and death after death, as we did before they vaccinated, quarantined or fumigated.”

Americans of that era were so much closer to death and disease it seems unimaginable to us now. Everyone knew someone killed or maimed by illness. The average life expectancy was 50. A third of all U.S. deaths occurred in children below the age of 5. Mary had lost two younger sisters in a span of two years, one of whom passed a mere 36 hours after her first sniffle arose. Death came so quickly that the family didn’t know which ailment to blame. But it wasn’t just disease that shaped social consciousness—everyday life was lethal. When Edward was young, a wagon full of corn rolled over his head. The wheel crushed his skull into the sandy road, lacerating his scalp above the ear. The resulting scar traversed half the equator of his head. As a baby, he snagged his bonnet on a barbed wire fence. His mother found him hanging, kicking his feet, his asphyxiated face dulled blue. Scarlet fever struck Edward’s little sister blind. Elsie, not yet 2, was quarantined in a room with her mother. The last thing she ever saw was her father kneeling at the door, rolling her an apple across the floor.

The county Health Department called to notify us that our house had been placed under a 14-day quarantine. No one in; no one out. We were fine on supplies, I assured them. My wife having spent the first week of the crisis squirreling away flour, pasta, rice, etc., and purchasing a quarter of freezer beef. My only contribution to our future survival was our dwindling firewood supply, a decade’s worth of .22 ammunition, and a cooler full of on-sale corned beef my wife had begged me not to buy.

Luckily, the illness never stole my hunger. But the dehydration was extreme. Over the next six days, the height of my struggle, I guzzled three gallons of electrolyte water a day and still my cells seemed parched. My body quaked like it was being chewed apart from the inside, at the microscopic level. Bolts of energy I’d never experienced—strange zips I attributed to my immune system straining its gears—sliced through my veins. I could feel my whole body engaged in the throes of survival.

In early March of 1918, a company cook, Albert Gitchell, reported to camp feverish and short of breath. He would go down as the first victim of a peculiar influenza strain that, over the course of several weeks, swept Camp Funston. The short-lived but virulent epidemic resulted in 2,480 reported cases and hospitalized more than 1,000 men. Upon their arrival, soldiers had received numerous inoculations, all of which proved powerless against this particular strain. Newspapers called it simply a spat of “Lagrippe.” By mid-April most signs of flu decamped, save the 400 convalescents still wracked by coughs and the bodies of 46 men the epidemic struck dead. As spring rolled on, troops shipped out, and few paid attention to the potential consequences of their diaspora. Only a small group of doctors raised the alarm after exhuming unusually limp, soggy lungs while conducting postmortem exams.

A letter my great-grandmother wrote to my great-grandfather in 1918.

Jeff Snowbarger

Though things had cooled at Funston, the strain, having stowed away in reassigned soldiers’ lungs, almost immediately began to boil up in Army camps nationwide. The speed with which it spread was breathtaking. Deploying from American posts, transit ships conveying fresh meat to the Western Front were hijacked by the virus, and once in Europe, the flu quickly raked the allied trenches and plagued civilian populations throughout Italy, England, France, and Spain. Wherever American soldiers beached, the virus went on a tear. By May of 1918, nearly three-fourths of the French army had succumbed to fevers, shivers, and aches. To everyone’s relief, summer saw case numbers drop, and by August, hopes flared that the pathogen was running out of steam.

Somewhere along the way, however, somewhere in the water-logged trenches, a humid field hospital, or a damp cathedral hastily converted to receive front-line casualties, a microscopic change occurred that spurred this influenza outbreak to become the most voracious plague since the bubonic days. Scientists believe, as it leapt from lung to lung, the virus morphed to work more synergistically with several strains of pneumonia-inducing bacteria. Once the influenza yoked its strength to secondary bacterial infections, the pathogen matured into an indiscriminate pestilence that mowed down young and old, rich and poor, sick and healthy alike. It was one thing to die in battle, for honor, glory, naïve excitement; it’s another, far more incomprehensible thing to go from a state of vim and vigor to drowning in your own juices in the span of a single day.

This was the influenza strain that returned to America in the late summer or early fall of 1918. Its circumnavigation had allowed the disease to shake its origins, which is why we don’t refer to the 1918 pandemic as the Kansas flu, as perhaps we should.

CALL IT “SPREE-ENZA” OR PLAIN SPANISH FLU: exclaimed a Topeka headline.

New Kind of Grip—You Swim on a Sea

of Sickness—Want to Die and

Can’t—It’s Some Ailment.

On Sept. 30, the flu first arrived in Mary and Edward’s letters, only as a “false alarm.” But soon, the outbreak was on everybody’s mind. On Oct. 2, a local doctor instructed readers of the Hutchinson Gazette:

It is easy to tell when one has this disease, because it is much more severe than even a very bad cold, and is accompanied by backache, headache—in fact aches all over. It may come on very suddenly, with bodily weakness, and the victim’s one best bet is to jump into bed and send for the doctor.

The next day, news broke: “The worst has come! Influenza, or ‘Spanish fleas’ as it is facetiously known to those who have not fallen into its clutches, descended yesterday upon three victims in Hutchinson … but there’s no system in going to bed, scared to death, the minute you begin to sneeze.” Clearly, a wickedly sick chicken had come home to roost, but at the time it was easy to joke about a “foreign” pestilence so few civilians had experienced firsthand.

Rural life had plenty of other worries. Some prairie folks still lived in dugouts, literal burrows in the earth. Mary’s letters mention family friends starting a new Colorado farm this way. Other settlers still lived in “soddies,” primitive rooms made of stacked prairie sod. Poor folk commonly shared roofs with gophers, pack rats, dogs, cats, chickens, goats, milch cows, rattlesnakes, and hogs. These pan-animal dwellings and the everyday closeness of human and animal life created ideal environments for pathogens to leap the species boundary, which is precisely how some experts believe the 1918 pandemic began. One Kansas family shared their dugout with a brood of burrowing owls that returned each May to rear new young in the same corner where the family kept their willow bassinet.

Six whole days my lungs felt limp, incapable of filling with air. My diaphragm seemed to seize like a blown piston. The underside of my sternum ached. The pressure was a bear that rode my chest. Since I was 10, whenever a similar breathlessness took hold, I could always suck my inhaler and achieve relief. Such spells never came more than a dozen times a year. But in the days following my ER stint, I found myself utterly dependent on my inhaler. Two puffs every four hours. Morning to midnight. No inhaler, no breathing. In the hours between, I had to think deep breaths into my lungs, mentally force inhalations past my bronchial forks and into the sore chambers starved for air. I kept my cellphone charged and a bag of clothes by the door.

On Oct. 4, Mary wrote to Edward explaining that she’d exhausted herself helping her father pick apples. She believed she’d worked herself sick. “It’s laughable to me now. … I don’t think I need any pity at all because I know it was my own fault.” Although the flu was nigh, Mary’s disposition remained hopeful. “I don’t mean to seem ungrateful to God for my health and I intend to be more careful. I sure want to live a useful life for Him. And even tho’ I see so much to do, around me I know God will give me the strength to do and He will never require more of me than I can do. I do realize that these are days when there is a plenty for everybody to do.”

What Mary didn’t yet realize was Edward had also fallen ill. In a previous letter, he’d broken the news he was “going to the trenches,” but this information did not affect Mary half as much as news that flu had sacked her fiancé. “I certainly think it was very considerate of you in not telling me you were in Hospital,” she wrote on Oct. 9:

Altho’ I have wondered many times how you are. And have prayed the Lord to be a wall of fire about you and shield you from the ravages of disease. And I’m sure “He has given His angels charge over thee.” I’m glad to know you has such a light case of it.

Her lover escaped the worst. After a week in the camp infirmary, Edward was released, but, for Mary, the reality of the influenza outbreak finally hit home:

Of course in reading so much about it in the papers, I couldn’t help but wonder if you would escape it. And at the same time I knew that you would be careful and also that you would be better able to throw off disease than if you were more “run down.” There are three cases of Influenza here in town and I’m not positive about it but heard that the schools are to close temporarily.

Mary’s gossip mill proved correct. That day’s Hutchinson Gazette reported: “Schools, Movies and Churches Closed by ‘Flu.’ ” In less than a week, rumors of a local outbreak had swelled into a public health crisis. Daily life changed overnight—“Alarming spread of epidemic causes drastic order by Health Board.” Not only were the main social hubs shuttered, authorities forbade public meetings “where more than 15 people may gather. … It was the only thing to do under the circumstances.” The following day, Hutchinson reported 28 new cases. Mary never complained about the church closures. She’d already experienced too much loss to believe God would heal and protect everyone she loved. Humbly, she understood that death sometimes usurps small liberties.

In a matter of months, the young couple discusses 25 sick mutual friends, five of whom end up dead.

The war still commanded headlines; influenza coverage often didn’t start until Page 3. But by now, the nation understood a new front in a different war had opened. Newspapers tallied mortality rates that proved two and three times higher than normal flus. “Even at the present stage,” a syndicate proclaimed, “it ranks as one of the worst plagues that has ever afflicted the country.” To keep the flu at bay, municipalities leveled severe restrictions. In New York City, “Sneezers and Coughers who fail to use handkerchiefs when the explosions occur in public are to be subject to $500 fine or a year in prison.” Entire towns blockaded themselves to keep out carriers. Condemned houses were torn down to build caskets from floor planks and siding, and before the ground froze, men dug mass graves. Cloth masks were everywhere. Quarantined homes set warning signs in windows. Even amid the nation’s massive plains, responses to the invisible vector caught everyone’s eye. As Mary noted, “We saw a number of Influenza cards as we were in town yesterday.”

Visibility, understandably, drove paranoia: “From what I read in the paper, I guess I had some of the symptoms of it,” Mary wrote, “but it was what I’d call a cold in my head. I had a start of it Wed. when I was writing to you and have been feeling rather ‘bum’ since then. Not bad enough that I couldn’t work but I have had to sneeze quite a lot and that just made me feel miserable.” Every sniffle, twitch, and ache became suspect. Every body was a source of fear.

Meanwhile, the flu continued to decimate Camp Funston. According to the Army Medical Department, September had seen 3,534 reported cases; in October, that number jumped to 11,290. The tide overwhelmed camp hospitals, relief organizations built temporary infirmaries, and the Army converted barracks to house battalions of sickened men. In all, Funston dedicated 22 buildings to the fight. The sudden strain on resources became so severe that healthy infantrymen, trained to join the trenches at a moment’s notice, filled in as nurses, sponging bodies, emptying bedpans, reading the bedridden magazines and mail, transcribing last desires and wills. Once recovered, Edward accepted “nurse duty,” knowing nothing of medicine but what he’d learned on the farm delivering foals and calves.

My great-grandparents.

Jeff Snowbarger

By late October, Hutchinson claimed hundreds of sick citizens. Mary expressed her dismay, writing, “It has really seemed rather alarming here because there were so many cases.” As often happened in her letters, alarm softened to existential contemplation: “How much these things ought to help us realize that life is very uncertain.” Eventually, the epidemic infected her letters as much as her habitual nods toward God. Responding to news that Edward kept busy attending military funerals, she pleaded, “May God continue to keep you in the hollow of His almighty hand.”

Others discovered the solace of quack remedies. One Hutchinson man touted the palliative magic of a particular “nasal douche and throat gargle.” The recipe, from a “celebrated New York physician, a specialist in disorders of the nasal tract,” consisted of “1 and ½ grains permanganate of potash, 90 grains chloride sodium (common salt).” The powder could then be divided into 20 doses, separately dissolved in hot water to create a pinkish pint that one could squirt up their nose. Another popular cure was an “Old Welsh Remedy” that included hot foot baths, opium, garlic, alcohol, and ice. Health officials regularly warned that “squirrel whisky was no cure for flu.”

“O, how wonderful it is,” Edward responded to Mary, “to be submissive to Jesus and trust him when all seems dark and unpromising.” Their letters don’t fully convey the pandemic’s brutality until names begin to appear—Ray Lange, Elmer King, Roger Winan’s wife, Brother Mendell, Mrs. Dunham and her family, Mrs. Mickey, and the Spurgeon family—“surely lots of folks needing help.” In a matter of months, the young couple discusses 25 sick mutual friends, five of whom end up dead. On visiting Mrs. Mendell after her husband passed, Mary wished she could have helped her with the wash, “But she said she was really better off when she was busy at something like that. She said she is so nervous and walks the floor and cries and grieves so much that she can see it is telling on her physically. So for that reason no doubt she needs something to occupy her mind and hands too.”

By January, Edward and Mary had experienced sufferings large and small, witnessed sickness and death on a scale that would have been unthinkable when they bid farewell on the train platform six short months before. Once the kaiser abdicated, and ink on the armistice dried, worry over Edward’s deployment shifted to the hope of discharge and the anticipation of coming home. After all, the couple had a wedding to plan.

Among all the letters they swapped, a January line lifts off the page. On hearing Edward’s discharge might still be months away, Mary wrote, “I want you to know that I am feeling fine.” It’s a subtle expression, a throwaway line, that without a sense of its darker context would read as trite filler. But surviving the fall of 1918 was a nearly providential feat. Amid an episode of wanton loss and private tribulation, relaying to a loved one that you are “feeling fine” is perhaps the truest, most honest way to gift another soul a boost of hope in the face of a shared, uncertain future.

Nearly two and a half months after I walked out of the San Fernando Cathedral, full breaths are still difficult to come by. Overall, I feel recovered. That is until my body reminds me I’m not and forces me to stop working, stop walking, stop reading, set the chainsaw aside, sit down, rest, now. While I can’t yet say that I feel fine, I can thankfully, gracefully say I am alive.

from Slate Magazine https://ift.tt/3bxyWAR

via IFTTT

沒有留言:

張貼留言